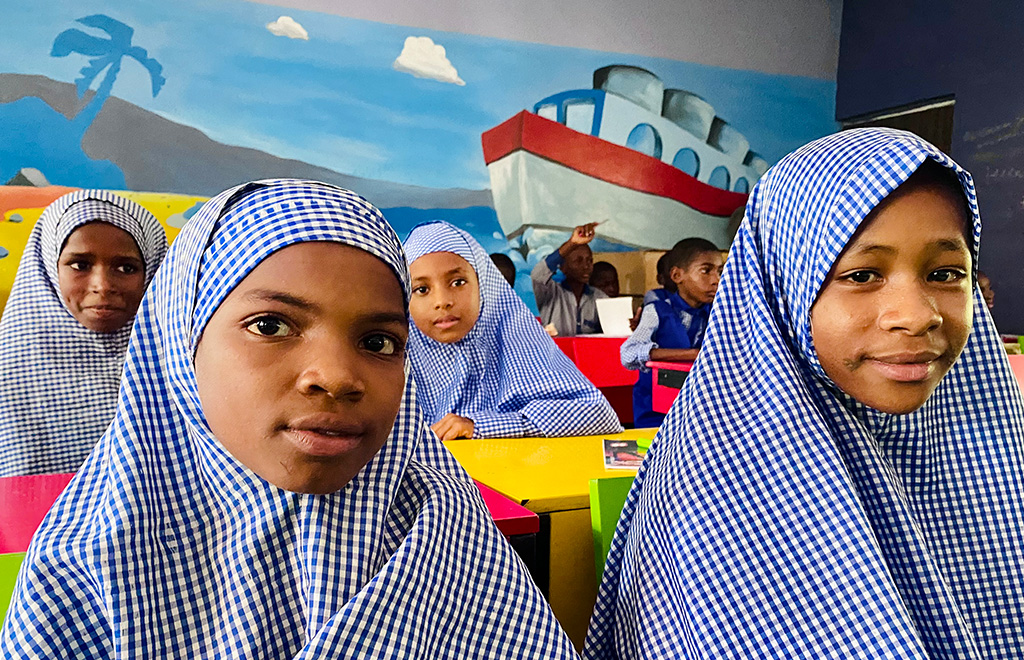

Tailored specifically for members of the Fulani community, living under displacement and poverty, the institution is giving 500 children an opportunity no one in their families had before.

In 2016, when the terrorist organization Boko Haram seized control of Abadam, a local government area in Borno State, North East Nigeria, Aisha’s family fled, leaving behind their livestock, farmland, and more.

The Fulani family sought refuge in Maiduguri, the state’s capital. They found shelter at the Shuwari II for Internally Displaced Persons (IDP) camp, joining thousands of others who had been uprooted by the conflict.

Aisha didn’t access formal education back in Abadam. Had she stayed there, she would have likely continued to tend cattle and, sooner than later, become a milkmaid. She may also have been married off at the age of 12. These are trends noticed amongst people in the community and Aisha’s circumstances.

But now, as the eldest child in her family, she is the first one to have the opportunity to go to school. Today, Aisha Malik is a secondary school student, among over 500 enrolled in the Aisha Buhari Integrated Secondary Fulani school in Maiduguri.

“I want to become a medical doctor to help my people; I also want to become a journalist to be seen on social media. In fact, I want to be everything,” she said.

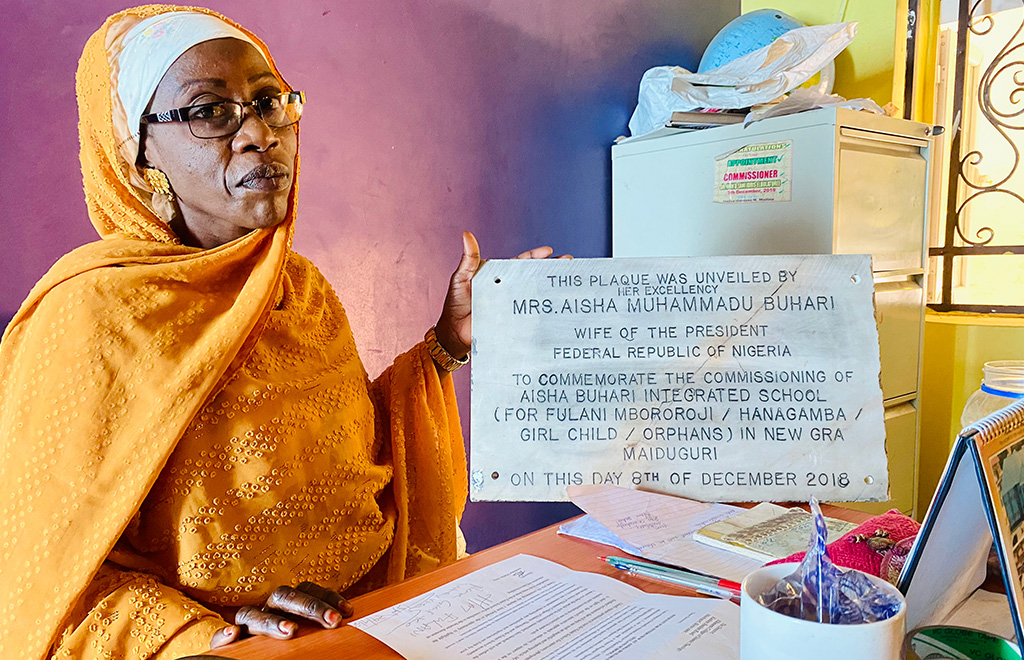

The school was founded by the Borno State Government in 2018, during the tenure of Kashim Shettima (the country’s current Vice President), with additional assistance from the Tertiary Education Trust Fund (TETFund) in the area which provided meals to the pupils, HumAngle gathered. It exclusively admits children from Borno’s Fulani community. “The aim is to break the cycle of intergenerational poverty and illiteracy among the Fulani community in Borno State,” said Shettima in 2017.

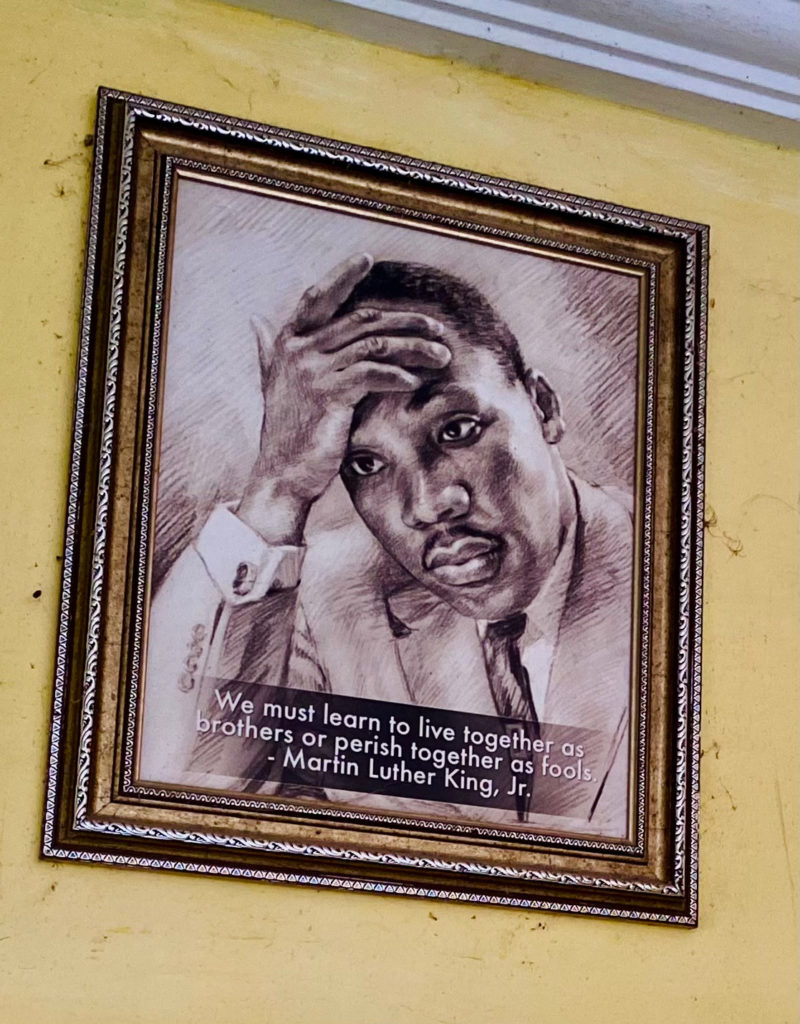

Named after a former First Lady of Nigeria, the school is adorned with colorful murals that spark creativity and curiosity among its pupils. Motivational quotes on portraits of renowned personalities across the world grace its walls, inspiring students with the stories of those who have achieved greatness. From Pakistani activist Malala Yousafzai’s unwavering dedication to promoting education for girls and women to Mae Carol Jemison, the first African-American woman to venture into space. Then, in the world of music, there was the legendary Billie Holiday.

The classrooms are equipped with air conditioning systems, vibrant murals, comfortable seats, and motivational portraits. Every classroom is designed to foster a thirst for knowledge.

Three school buses transport students from their respective locations every morning to the school and back. The school also provides breakfast and lunch.

Their aspirations

Abubakar Mohammad Bello is the first to attend school in his entire family. “I aspire to become a Nuclear Engineer, enabling me to safeguard my country in the future against potential threats and insecurities from foreign nations,” he said.

All the pupils interviewed by HumAngle are the first to attend school in their families. Some of their parents work as property guards, earn as little as ₦5,000 (approximately $5) per month, and sell tea. Despite their hard work, they cannot afford to send their children to formal schools.

Another student, Hassana Mai Agolla, a school press club member, said she wants to become a journalist because she is passionate about newscasting. Then there is Mohammad Usman Yunusa, who desires to become a school teacher. He justified his choice by quoting a hadith: “The best among you are those who learn and teach it.” He added, “I want to teach all that I am learning to my younger ones.”

The desire to defend their country resonates with some of the pupils. Abubakar Mohammad, a primary four pupil, hopes to someday join the Nigerian military to contribute to national security.

Losing it all

Several parents told HumAngle how they lost their cattle to the insurgency that has ravaged the state for more than a decade. In 2016, one of them, Usman Yunusa, was jolted awake by the echoes of heavy gunfire in Abadam. Boko Haram had seized control of the town, prompting him to gather his family and abandon his livestock. They trekked for over a day before they reached Maiduguri.

After reaching Maiduguri, Yunusa and hundreds of others settled in Shuwari camp II. He spent a year frequenting the cattle market, desperately hoping to reclaim his lost cattle. Regrettably, his efforts proved fruitless; there was no trace of his prized possessions.

Displaced, many others occupied construction sites and uncompleted buildings. They became security guards and laborers. They also hawked tea on the streets. But these were not enough for them to give their children the upbringing that would enable them to have a chance at a bright future. School seemed like a tall dream.

Reflecting on that period, Yunusa remarked, “The most positive outcome since losing forty cattle is witnessing my daughter attend school.”

In the vastness of Nigeria’s landscape and its diversity, the Fulani community is known for its unique way of life. Traditionally known for its nomadic lifestyle, they have roamed the West African plains for centuries, tending to their cattle. But insecurity and climate change have rendered many of them pastureless and unable to continue the trade; they have to come to cities and try to adopt lifestyles that are alien to what they are used to.

However, while their nomadic traditions have deep historical roots, they have also posed significant challenges, particularly in education. The Fulanis’ migratory lifestyle, dictated by the needs of their livestock, has made access to formal education a major hurdle for their children.

The head of Fulani settlers in Borno State, Zanna Rebo, said, “Whenever the word Fulani is mentioned in Nigeria, the first thing that comes to mind is banditry and kidnapping. The Fulani people were unfairly associated with these criminal activities without being given an opportunity like others. But here in Borno, our children are given opportunities to obtain an education. These children would have grown up without skills and knowledge to cope with the new world and might be exposed to criminal activities, but now they are rescued from such calamity.”

“The livestock that they inherited have been rustled, and their farmland cannot be accessed anymore, all because of Boko Haram insurgents. They are not educated; the system has cheated them. The narrative has been changed for some of these children; now all they think of is how Nigeria will progress,” he said.

Zanna Rebo observed that, before now, the children didn’t even know how to say “come” in English. Today, they speak English, Arabic, and other local languages.

“The opening of Aisha Buhari Mega School has brought hope to our children’s future in Borno State. They now have access to education, digital skills, and self-realization,” he added.

“In other places, we hear of Fulani tribesmen engaging in kidnapping, armed robbery, and other vices, but, in Borno State, we have been treated differently for a long time, which highly contributed to our peaceful coexistence in the region,” said Ferroje Ahmed, parent to three of the school’s students.

He has lived in Maiduguri for over 20 years. “I feel hopeful when I remember that my children will not suffer the consequences of lack of education when they grow. They now have equal opportunities with others,” he added.

Ahmadu Yugudu, a displaced Fulani farmer from Kukawa local government area, has two children enrolled. “I couldn’t have sent them to school without this scheme. The Fulani school is my children’s only hope,” he said.

“There is no place in Nigeria where we heard of or have seen our children taken to special schools apart from Borno State. This is a welcome development, and it could serve as a template for other states to follow as a long-lasting solution to insecurity,” said Usman Husaini, the chairman of the Fulani herders association in the state.

The chairman further added that the only time they heard of such social involvement was during Nigeria’s colonial and military era. He pointed out that they have been neglected even though they contribute immensely to the economy of Nigeria and Africa through the cattle business.

According to the National Commission for Nomadic Education (NCNE), the commission is mandated to cater to the educational needs of the socially excluded, educationally disadvantaged, and migrant groups (herders) in Nigeria because these population segments face significant barriers to accessing primary education due to occupational and socio-cultural factors.

Out of the estimated 10.4 million migrant groups in Nigeria, about 3.6 million are children of school age, of which only 519,018 are currently enrolled in schools. The participation of nomads in existing formal and non-formal primary education could be much higher. This justifies Nomadic Education as a strategy for inclusiveness to primary education for nomads in Nigeria.

Their lifestyle

The head teacher, Sa’adatu Garba, explained that a significant number of children within the nomadic community encounter distinctive challenges due to their itinerant lifestyle. One is the frequent change in residence due to the nature of their parents’ jobs. Once construction is completed at their temporary sites, such families must seek new accommodations, often accompanied by their children. This poses a significant hurdle to their education.

“Sometimes, we categorize these children as dropouts, only to witness their return after several months with various excuses. Our only recourse is to embrace them with open arms, as our entire endeavor is dedicated to their welfare. Any form of punishment or coercion leading them to drop school would severely blow the initiative,” said Sa’adatu.

Sa’adatu also pointed out the need for more classrooms, a science laboratory for practicals, an ambulance or school health facility, and textbooks for the children. “Next year, we will have students sitting for their Senior Secondary School Examination. We will need a laboratory for the science practical examination. Also, extra classes are needed because we now share the school facility with the host community. The students have a strong passion for reading, which is limited because they do not have what to study with at home.”

“The Fulani herders, for whom the Fulani school in Maiduguri was established, are nomadic pastoralists who roam with their cattle, constantly searching for lush pastures. Over the years, the pastures they rely on have, for various reasons, become increasingly inaccessible to them. This, in turn, has taken a toll on their livelihoods, rendering them more vulnerable. As history has shown, when people lose their means of sustenance, their vulnerability can potentially lead to social instability,” said Dr Omovigho Rani Ebireri, a lecturer in the Department of Continuing Education and Extension Services, University of Maiduguri.

Ebireri explained that creating a well-equipped school, staffed by qualified and experienced teachers capable of capturing the attention of these herder children, is commendable. “This is not a far-fetched notion; it echoes the wisdom of Chief Obafemi Awolowo, who once said, ‘The children of the masses you fail to educate today will prevent you from sleeping tomorrow.’ This statement encapsulates the essence of the matter precisely.”

This story was originally published in HumAngle (Nigeria) and is republished within the Human Journalism Network program, supported by the ICFJ, International Center for Journalists.

The Aisha Buhari Integrated Secondary Fulani school in Maiduguri, founded in 2018 by the Borno State Government, is providing education to over 500 children from the Fulani community, traditionally known for their nomadic lifestyle. This initiative aims to break the cycle of intergenerational poverty and illiteracy among the Fulani people, who have suffered greatly from the Boko Haram insurgency.

For many students, like Aisha Malik, this school represents the first opportunity in their families to receive formal education. The amenities include air-conditioned classrooms, vibrant murals, comfortable seating, and motivational portraits of famous personalities, all designed to inspire and foster a love for learning. The school also provides transportation and meals for the students.

Despite their displacement and the consequent loss of their livelihoods, families find hope in the new educational opportunities. The pupils express diverse aspirations, ranging from becoming doctors and journalists to engineers and military personnel. These dreams highlight the transformative power of education in reshaping their future and communities.

The challenges are significant, including frequent relocations due to the nomadic nature of their parents' work and the need for more educational resources and facilities. However, the initiative has brought a renewed sense of hope and a potential model for integrating marginalized communities through education in Nigeria.

The Fulani community leaders express gratitude for the initiative, noting it as a hopeful development against the backdrop of their struggles. The school stands as a testament to the possibility of social change through education, providing a template for addressing broader issues of insecurity and poverty in the region.