In northern Nigeria, there is a history of vaccine hesitancy leading to several vaccine-preventable diseases. Can providing cash incentives to caregivers encourage vaccination and reduce the disease burden? One organisation thinks so, and it has been doing it since 2014. But how does this work? That’s the question this story answers.

Gombe, Nigeria : It’s 8 AM on Monday, August 26, 2024, at the Pantami Primary Healthcare Centre in Pantami, a suburb in northeast Nigeria’s Gombe State. The children’s vaccination hall is filled with a vibrant array of hijab colours—green, brown, white, and more, representing a mix of young and older mothers who had brought their babies and toddlers for vaccination.

Among them is 37-year-old Ashaitu Adamu, a mother of three. Inside the hall, a healthcare worker, dressed in a grey scrubs, calls a number and Ashaitu moves forward with her 15-month-old toddler, Fatima. The worker collects Fatima’s vaccination card, verifies it against the centre’s records, and directs Ashaitu to another section in the hall.

There, Fatima receives her final dose of the MCV vaccine, which helps prevent the bacteria that causes measles in children. Measles is an airborne disease that the World Health Organisation describes as “highly contagious”.

But this last dose, which is also the last of the doses of various vaccines she had been scheduled to take, means more than just disease prevention; it is also a hunger reliever for Ashaitu’s family. The dose makes Ashaitu eligible for a N5,000 ($3) livelihood support.

“My husband has not received his salary and I left the house after morning prayers. My husband will come back to see food in the house today, all thanks to this money,” she says.

By 10 AM, the room still has at least 50 women with their children waiting for vaccinations.

“It hasn’t always been like this,” says Khalid Dauda Boi, the facility’ routine immunisation officer, implying that mothers scarcely brought their children for vaccination until a cash incentive was introduced. “We often had to go out and persuade women to bring their children for vaccinations.”

The change from vaccine apathy among mothers to ensuring their kids are fully immunised is thanks to an initiative that rewards caregivers like Ashaitu in several northern Nigerian states for being consistent in ensuring full immunisation of their children.

Fighting disease with conditional cash transfers

This cash support is a program of New Incentives, or NI. This US-based nonprofit founded in 2011 believes that lack of money for poor families means they prioritise daily survival, leaving little attention to activities that improve family health or educational outcomes. It refers to its cash incentives as conditional cash transfers.

“A conditional cash transfer is a small amount of money given to somebody in need after they participate in certain activities, and that could be…preventative healthcare,” said its founder, Svetha Janumpalli.

In Nigeria, NI carries out its activities as All Babies Are Equal Initiative, a local organisation it founded in 2014, and it works to drive child vaccination in poor communities across nine northern Nigerian states.

The north and vaccine hesitancy

Nigeria, Africa’s most populous country, grapples with a high burden of vaccine-preventable diseases, including meningitis, polio, and measles. A 2019 study by Gavi Zero Dose Learning Hub estimates that at least 41% of deaths among children under five in Nigeria may be vaccine-preventable.

But vaccine distrust, especially in the Muslim-dominated north, is a major obstacle to disease prevention. The hesitation is understandable, and it stems from Pfizer’s 1996 failed meningitis vaccine trial that left 11 children dead and more with permanent disabilities.

In 2003, Muslim leaders in Kano State led a 15-month boycott of the polio vaccine. The result was a 30% surge in confirmed polio incidents in the country amid a national effort to attain a polio-free status.

Insecurity in the region has also slowed down immunisation rate. For example, nine immunisation workers were shot dead in Kano by gunmen suspected to be members of Boko Haram insurgents.

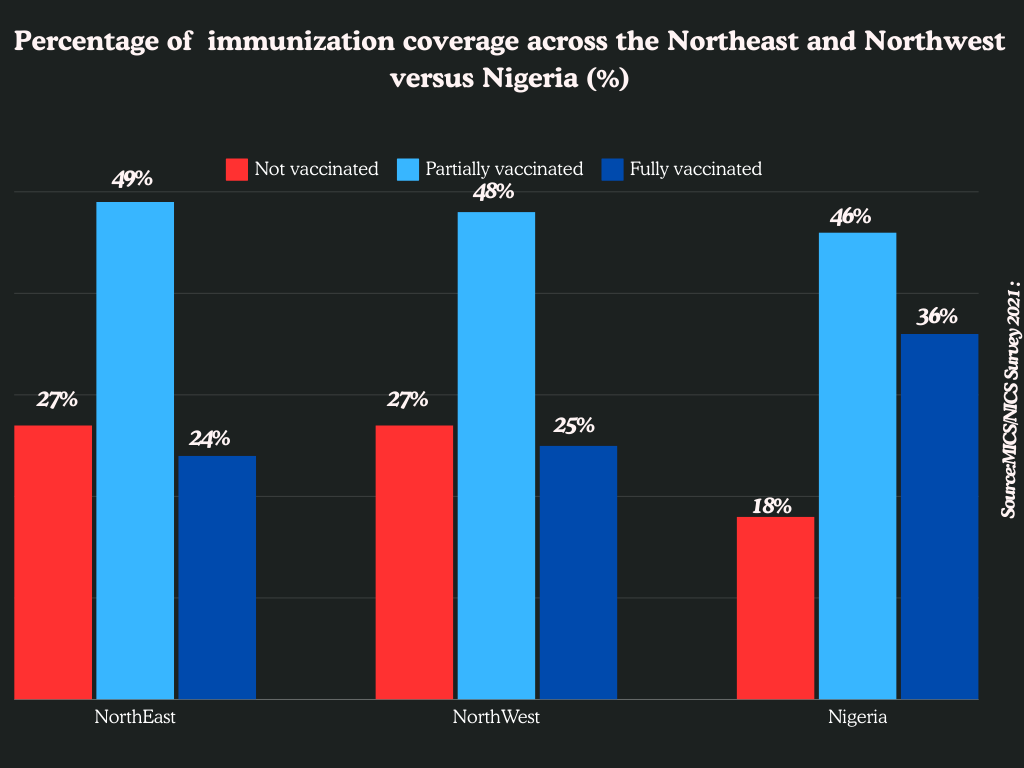

By 2021, according to figures from the Multiple Indicator Cluster Survey/National Immunization Coverage Survey, the regions of the northwest and northeast (where Gombe State is), recorded the highest numbers of unvaccinated children. The northeast, in particular, had 27% zero-dose vaccination rate, a 49% partial vaccination rate—the highest in the country. Overall, the region had just 24% vaccination coverage, falling short of the national average of 36%.

The little cash that means much

New Incentives provides a N1000 ($0.60) cash incentive to eligible caregivers (parents) each time their child takes a vaccine dose as scheduled. “That encourages them to come to the facility for immunisation,” said Abdurrahman Shaibu, executive director of the Gombe State Primary Health Care Development Agency.

After the final dose of the last vaccine, a caregiver receives N1000 and an additional N5,000 ($3) for adhering to the vaccination schedule to the end.

For many women in poor communities, the absence of such incentives means they cannot afford transportation fare to vaccination centres, and that can be a major reason for missing schedules for their babies and toddlers.

In the last decade, a cost of living crisis set off by heightened inflation has driven Nigeria’s poverty rate to a staggering 40.1%. More than 40 million women—mostly in the northern region—live in extreme poverty. Last year, the cost of transportation in the region rose by over 90%.

“Sometimes, I wake up with no money,” said Patience Joy, a caregiver, emphasising how she would have missed vaccination appointments if NI was not supporting her transportation costs.

Partnership-driven

The nine out of the 19 northern states NI operates in are Bauchi, Gombe, Jigawa, Kaduna, Kano, Katsina, Kebbi, Sokoto, and Zamfara. Intervention in a new state begins with a rapid assessment, which is a “baseline survey to understand the vaccination coverage level in that area,” said Mustapha Kabir, operations coordinator for northwest and northeast.

After six months of operating in such locations, “We try to collect data to assess the level of improvement,” Kabir added.

The organisation heavily relies on partnerships with local state authorities, such as the Gombe State Primary Health Care Development Agency, to operate. It also works with local chiefs and religious leaders, who wield significant powers in rural communities, to raise awareness about the benefits of vaccination.

NI clarifies that it does not provide vaccines but works to identify and address barriers to vaccination and non-compliance cases.

“It is government agencies and immunisation partners who procure vaccines and play all active roles in the supply chain. Our role involves coordination and communication to identify and resolve supply issues and bottlenecks. All of this supportive work is carried out with our government partners at the local, state, zonal, and national levels,” it says on its website.

But “We also aim to improve the quality of local healthcare facilities by ensuring proper documentation and that clinics are active and serving the required caregivers,” adds Kabir.

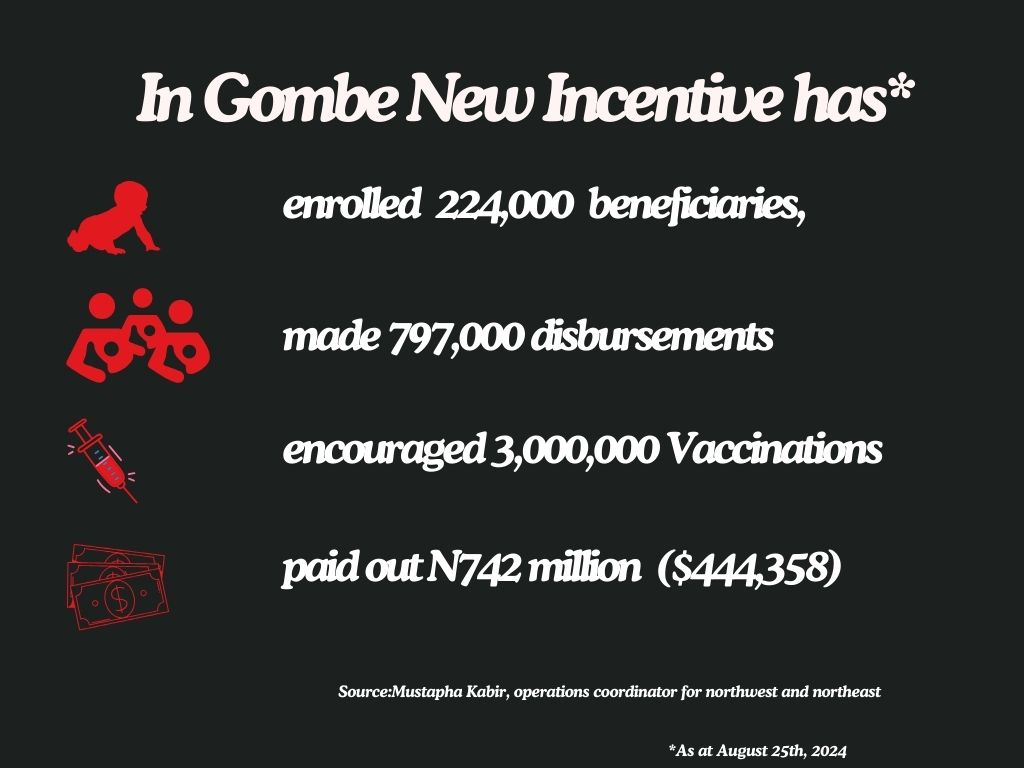

He said in Gombe alone, NI has enrolled about 224,000 beneficiaries, made 797,000 disbursements, amounting to about N742 million ( (about $444,358) and has encouraged over three million vaccinations.

Shaibu, the director of the Gombe State Primary Health Care Development Agency, said his office uses harmonised data, community surveys, and feedback from community healthcare facilities to measure the impact of NI’s program. “The result shows a significant increase in demand for immunisation across our primary healthcare facilities,” he admitted.

The secretary at the Pantami Primary Healthcare Center in Pantami, Ahmed Mohamed Bello, agreed. “The number of caregivers over the last two years has more than doubled,” he said. “Without the new incentives, we might have only seen a third of the usual turnout.”

A new problem

The influx of mothers into health centres seeking vaccination has created a new problem for the centres: A shortage of healthcare workers to effectively meet the demands.

And despite efforts to fight vaccine distrust, some husbands still remember the failed Pfizer incident and continue to prevent their wives and children from receiving the vaccine.

But those who have been receptive say they have evidence that the vaccines have been helpful.

“I now know the benefit of the vaccination. My children don’t have these common childhood illnesses,” Aishatu said.

In northern Nigeria, cash incentives are being offered to caregivers to encourage childhood vaccinations and reduce vaccine hesitancy, which has historically led to high rates of preventable diseases such as meningitis and polio. The New Incentives (NI), a U.S.-based nonprofit operating as All Babies Are Equal Initiative, uses these incentives in nine northern Nigerian states, including Gombe. Caregivers receive small cash transfers for each scheduled vaccine dose completed, culminating in a larger incentive if the full vaccination schedule is adhered to. This approach has significantly increased attendance at health centers for vaccinations, though it has also highlighted issues such as understaffing at healthcare facilities.

Vaccine hesitancy in the region is rooted in distrust caused by past events like the failed 1996 Pfizer meningitis trial, which caused harm to children, and the 2003 polio vaccine boycott led by Muslim leaders in Kano. Despite these challenges, the cash incentives have proven successful in increasing immunization rates and addressing economic barriers such as transportation costs, which many impoverished families face.

The initiative is supported by partnerships with local government, community leaders, and healthcare agencies to promote vaccination and improve local healthcare infrastructure. However, despite the program's success, challenges remain, such as the persistent shortage of healthcare workers and some continuing vaccine distrust among families remembering past medical trials' failures. Nonetheless, those participating have reported fewer childhood illnesses in their immunized children, underlining the program's positive impact.