Nigeria’s February 25 (2023) presidential election remains controversial, gathering comments from worldwide. The primary issue unsettling the nation’s political space since the winner’s announcement is the failure of the Independent National Electoral Commission or INEC to fulfil a significant promise it made to Nigerians before the election.

INEC had promised to transmit results from polling units to its results-viewing digital portal, the IReV.

The promise of electronic transmission sparked uncommon youth enthusiasm demonstrated throughout the electioneering period because the youths hoped for a transparent and fair election. It became baffling when the election management body failed to deliver on that solemn promise but instead did manual transmission.

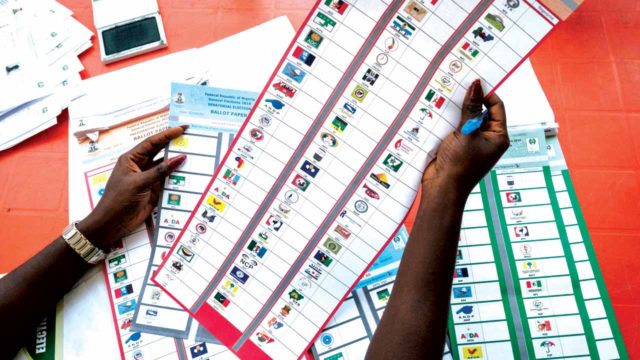

However, this analysis is not targeted at the integrity or otherwise of the presidential election, but one of the salient issues it has thrown up. A major poll fallout is the number of rejected or invalid votes, which is expected to trigger national discourse post-election.

According to the results announced by the INEC chairman, Mahmoud Yakubu, 939,278 out of 24,965,218 total votes were invalid, representing 3.8%.

A flashback to previous elections reveals that the country recorded 1,2989,607 invalid ballots in 2019, representing 4.5% of the total 28,614,190 votes. The winner, now outgoing president Muhammadu Buhari polled 15,191,847 to beat Atiku Abubakar of the PDP, who scored 11,262,978.

Disturbingly, the invalid votes of that election were higher than the votes garnered by the candidates of all other seventy-one political parties that took part. Also, the number was greater than the total valid ballots cast in each of the 34 states, including the Federal Capital Territory (FCT), except for Kano, Kaduna and Katsina, where useful votes were put at 1,891,134, 1,663,603 and 1,555,473, respectively.

In 2015, 844,519 votes were declared invalid nationwide, constituting 2.8%t of the total 29,432,083 ballots cast.

The situation was not better in 2011 when 5.3% of the votes were invalid.

Apart from the poll’s winner, the first and second runners, and the candidate who came fourth, no other candidate in the 2023 presidential poll garnered votes up to the number of invalid ballots.

With this in mind, what would have been the case if the law did not permit trusted persons can assist those who cannot vote on their own? The number would have been far above what it is.

Why rejected votes?

Why does the country continuously record such many invalid votes, sometimes huge enough to compel a rerun in keenly contested elections?

“I must tell you that the majority of rejected ballots result from poor knowledge of the process. People still do not know that it becomes invalid if you fold wrongly and the ink touches another party,” said an election expert, Austin Aigbe.

“They have to fold vertically to ensure that even if the ink touches the party logo, it will be the same party you vote for. I have seen where a particular voter thumb-printed for all the parties. Some persons take pens into the voting cubicle and sign at the back.”

Aigbe said there is a great need to extensively educate voters in local languages about the process, especially not-too-literate rural dwellers.

“Unlike in urban areas where people speak English, if you promote voter education in the three major languages in the country, you have actually sidelined several millions of people more than three hundred ethnic groups, and you won’t achieve much.”

Elvis Okolie, a political scientist, identified vote buying and selling as another causative factor.

“In some circumstances, voters are under pressure from representatives of various political parties; some might have even collected money from at least two parties. In their effort to hide their ballot papers so nobody sees them as they put into the [ballot] boxes, the votes become invalid,” he said.

The implication of high invalid votes could be problematic.

“It can, in critical cases, give electoral victory to the person majority of voters did not elect,” Elvis submitted,” Okolie said.

Voter education, whose duty?

Sustained voter education has been identified as a massive step towards reducing the problem of invalid votes. But whose duty is it?

“Unfortunately, the political parties still rely on INEC for voter education. I agree; the constitution empowers INEC to do that. But political parties should do their job as the greatest beneficiaries of elections,” Aigbe said.

“You see the civil society and the media helping out. But, when the parties who go to educate the electorate well, it will be more efficient. The CSOs, the media and INEC have done their jobs consistently, yet we continue to see rejected ballots. It is time for the parties to take leadership in voter education so that whoever votes for them votes correctly. The rest of us will continue to complement.”

For Elvis, “It is the work of the National Orientation Agency or NOA,” he said, blaming the NOA for inactivity.

“I don’t know if NOA still exists. After the NOA, the political parties and the candidates should do their work creditably as the eventual beneficiaries of the votes. After all, invalid votes could cost them victory.”

Electronic voting can help

Electronic voting is currently not practised in Nigeria. But it is one identified means of cutting down the number of invalid votes.

“As it is, many people voted correctly; it is in the process of putting the paper into the ballot boxes that the votes get invalidated. Electronic voting will eliminate the problem of invalid votes,” Aigbe explained.

“Now that the Electoral Act 2022 has given INEC the full power to deploy any technology into our electoral process let INEC upgrade the BVAS so that we can use it to vote. Once the voter is accredited, he goes into the cubicle and clicks on the party he wants to vote for.”

He argued that electronic voting would also drastically reduce the massive cost of conducting elections in the country since it would reduce the need for ballot paper printing and ink buying.

Despite its struggling economic state, Nigeria spent 300 billion naira (over $135 million) on the conduct of this year’s general election, and the bulk of the money went into the printing of ballot papers.

While national discourse will undoubtedly continue around the imperative of Nigeria switching to electronic voting, there is an urgent need to reverse the ugly narrative of invalid franchise, especially as the country conducts the governorship and state house of assembly elections this weekend.

Nigeria's February 25, 2023, presidential election has been controversial primarily due to the Independent National Electoral Commission (INEC)'s failure to keep its promise of electronically transmitting results. This lapse generated significant disappointment, especially among the youth who were eager for transparency. Instead, manual transmission was used, raising concerns about the integrity of the election.

The election also highlighted the issue of high invalid votes, with 939,278 out of 24,965,218 total votes deemed invalid, accounting for 3.8%. This percentage is slightly lower than in previous elections, such as 4.5% in 2019 and 5.3% in 2011, but still significant enough to impact outcomes. Invalid votes often stem from a lack of voter education, with improper ballot handling and voting under pressure contributing to the problem.

Experts like Austin Aigbe and Elvis Okolie emphasize the need for better voter education, particularly in local languages for rural areas. Political parties, rather than relying solely on INEC, should take a more active role in educating their electorate to avoid invalid ballots. Additionally, there are calls to implement electronic voting, which could eliminate invalid votes and reduce election costs, as exemplified by Nigeria's spending of over $135 million on the recent elections.

The discourse around electronic voting continues as Nigeria prepares for its governorship and state house of assembly elections. Addressing the issue of invalid votes remains critical to ensuring the integrity of future elections.