One harmattan morning in January, I met Saidu Adamu under the shade of a sprawling mango tree. At 47, Adamu’s face was scarred with intricate tribal marks that pointed to his many years of rearing cattle between settlements.

Outside of a tsangaya (Qur’anic learning centre) where he learned to read the Qur’an during his boyhood days, Adamu had never attended a formal school.

Growing up in Garin Buba, a windswept settlement nestled in Central Taraba State, Adamu knew only cattle herding, as it was a legacy passed on to him by his forefathers.

“Farming and herding were the way of life for us. Since we inherited it from our parents, you don’t expect us to abandon it. And that’s why school didn’t hold any significant importance to us then,” Adamu told me.

The following Tuesday morning saw me navigating narrow pathways deep within a forest until I arrived at Garin Yau, a settlement in Mayo Selbe ward of Central Taraba State. Here, I encountered Alhaji Yau Hassan, whose back was pressed against the wall of his hut. He had earlier planned to deliver salt licks to his distant cattle herd, 23 kilometers away, but upon hearing about my visit, he stayed back to speak with me.

As with Adamu, Yau, 50, had undergone Islamic education at a tsangaya in Mayo Kam while as a child. After completing a pilgrimage to Makkah, Saudi Arabia, at the age of 31, he was crowned “Alhaji,” a revered title in Muslim communities.

Yau was the first person to settle in what is now Garin Yau, a stack of 15 to 16 mud-brick huts enveloped by rolling hills and towering trees. Residents of Garin Yau, who are all Fulani, are bred on cattle and goat herding, with no introduction to formal learning. “We only knew herding,” Yau admitted.

In 2021, Yau explained, the Gashaka branch of the Fulɓe Development and Cultural Organisation (FUDECO) presented a new perspective to put paid to this age-old tradition within the communities of Garin Buba and Garin Yau.

“They told us that through education, we can build a future where traditional skills could be combined with modern knowledge so as to live a better life,” Yau said.

FUDECO: Empowering pastoralists communities

Sarli Sadou Nana, who founded FUDECO in 2017, explained that he was driven by a desire to minimise the suffering of pastoralist communities. “We want to enhance pastoralism in Nigeria and across Africa to modern standards, which in turn, will generate economic opportunities necessary for the development of the pastoralist communities,” Nana said.

FUDECO works at the intersection of humanitarian aid, development, and participatory research. Its primary mission is to empower pastoralists by preventing and managing conflicts, advocating for equal rights and participation in decision-making, and ensuring access to essential services like water, healthcare, and veterinary care.

Beyond these, the organization helps communities adapt to the challenges of climate change, expanding its reach to other Nigerian states and local government areas, including the Gashaka branch, founded in 2021.

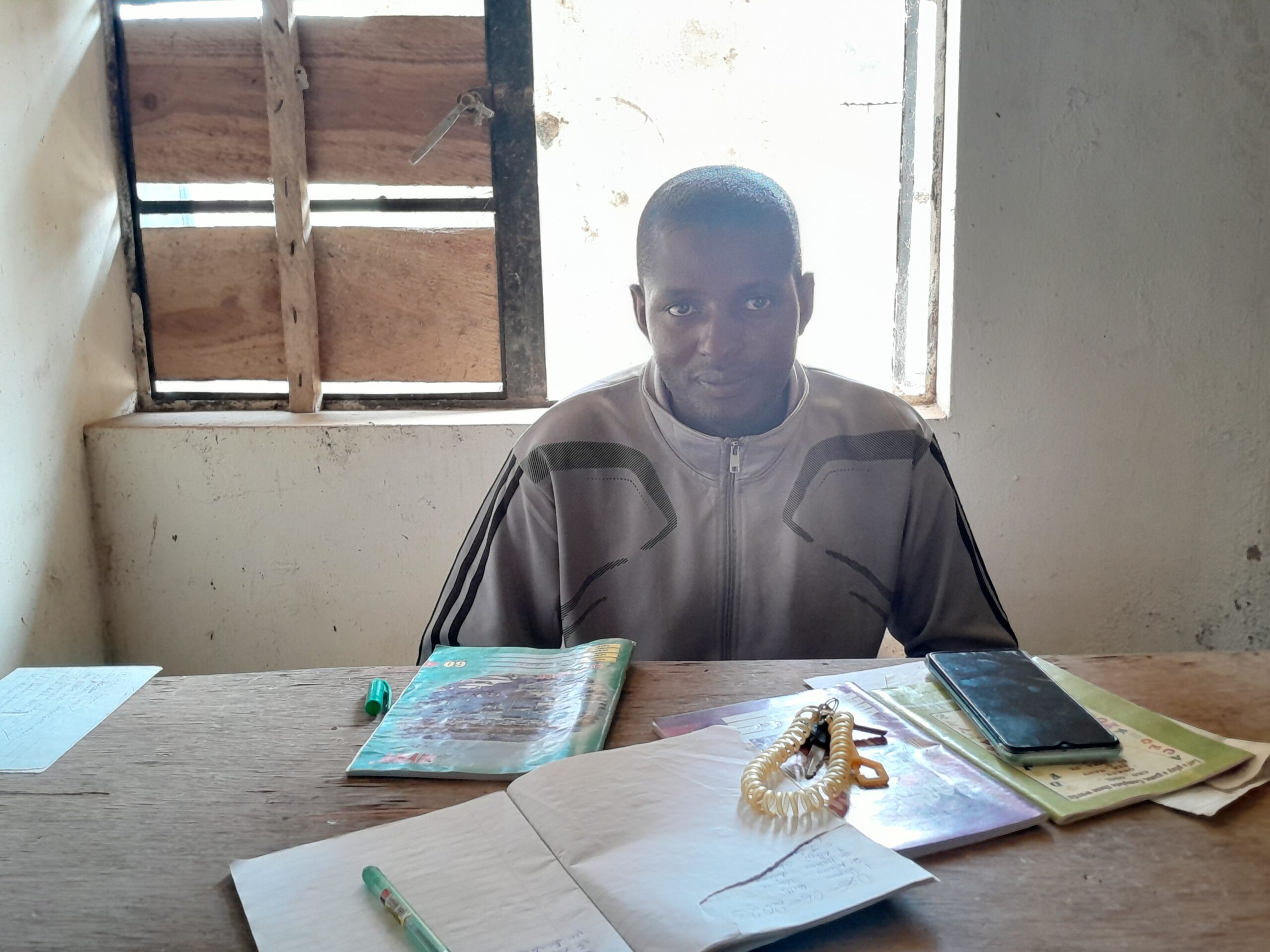

Prior to visiting Garin Buba and Garin Yau, I went to FUDECO’s Gashaka office in Serti town. There, I met with the branch chairman, Usman Bello, who discussed more about the activities of the outfit.

“We began with just three people, and thanks to support from community leaders, we grew to over 100 members,” said Bello, propped up on a wooden chair and flanked by other members. “We then continued with identifying the problems facing Fulani communities and used FUDECO’s network to address them.”

This was no mean feat at the start. Some community leaders expressed misgivings about the intervention. But Bello and his team soldiered on, tirelessly explaining the importance of education. Once the community opened up to them, they started classes under trees, using volunteer teachers.

As funding became limited, FUDECO Gashaka sourced funds from its national branch, donations from members, and even from social media. The funds thus accrued were used to build a couple of classrooms in each of the communities.

Embracing change

Adamu and Yau have since embraced this new ideal and have moved to enrol their children in lessons on basic numeracy and alphabetical skills.

“It was initially difficult to accept this new idea,” Adamu admitted. But as he and other parents saw the potential of this learning for their children, they decided to support it.

Similarly, Yau expressed, “Most of my children are grown now and have started their own families. Therefore, I took responsibility for enrolling my remaining young children and grandchildren.”

Adamu not only enroled his four children, but he also went ahead to convince other members of his extended family to enrol theirs. As a respected figure, his words carried weight, so they followed his advice.

The views of many parents like Adamu and Yau across rural communities in Gashaka have since changed, and they are now fully involved in the education of their children.

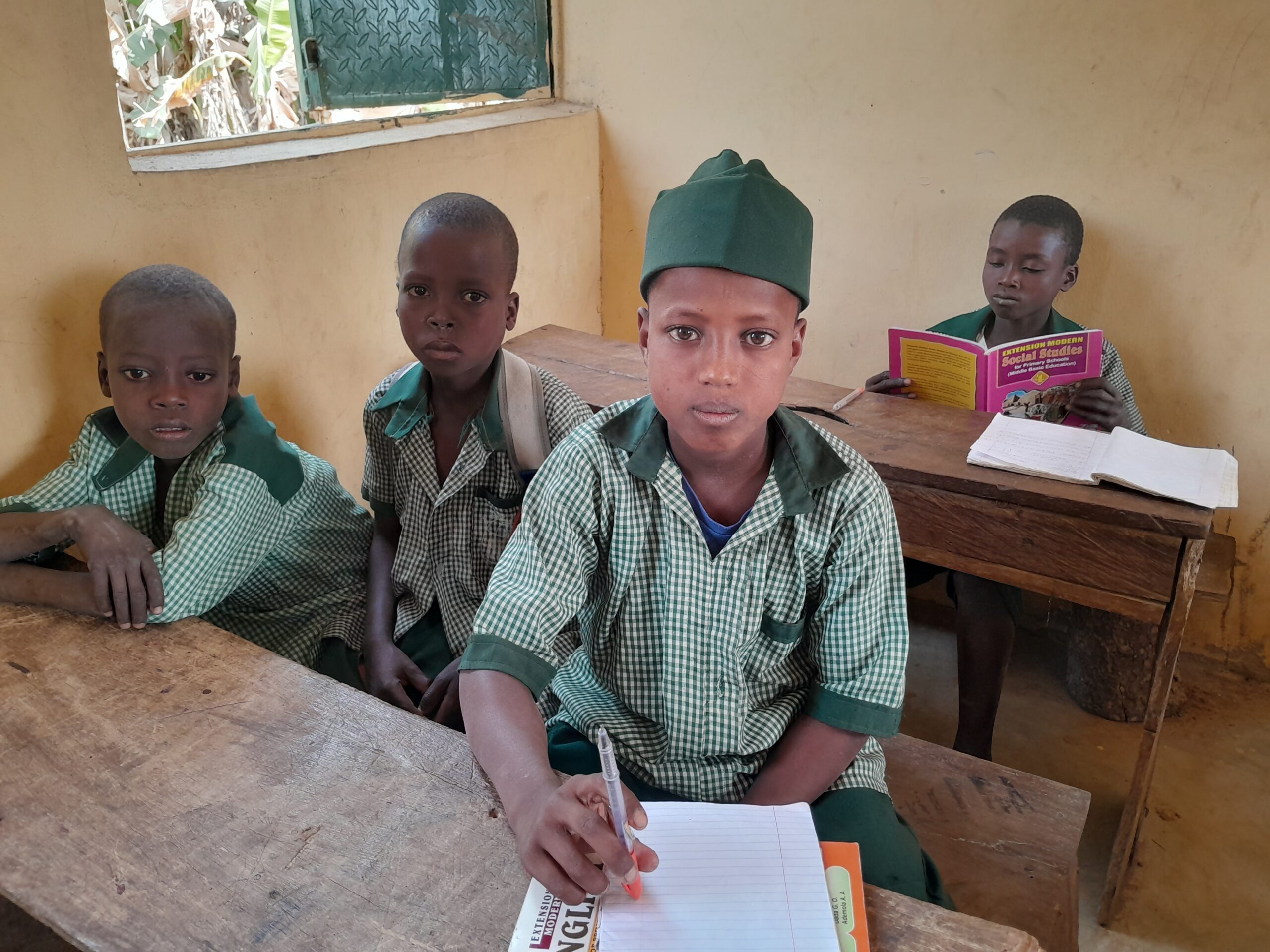

On the morning I visited Garin Buba, after my conversation with Adamu, I took a few steps towards the building that served as Garin Buba Community Primary School. Built by FUDECO Gashaka, with aid from Women in Da’awa Initiative, a faith-based organization, the school comprised three classrooms. As with other communities, lessons first began under a mango tree before its moved into a permanent structure.

In one of the classrooms where about 41 students were gathered, I observed their faces rapt with attention as they listened to a teacher who introduced himself as Abubakar Abdullahi.

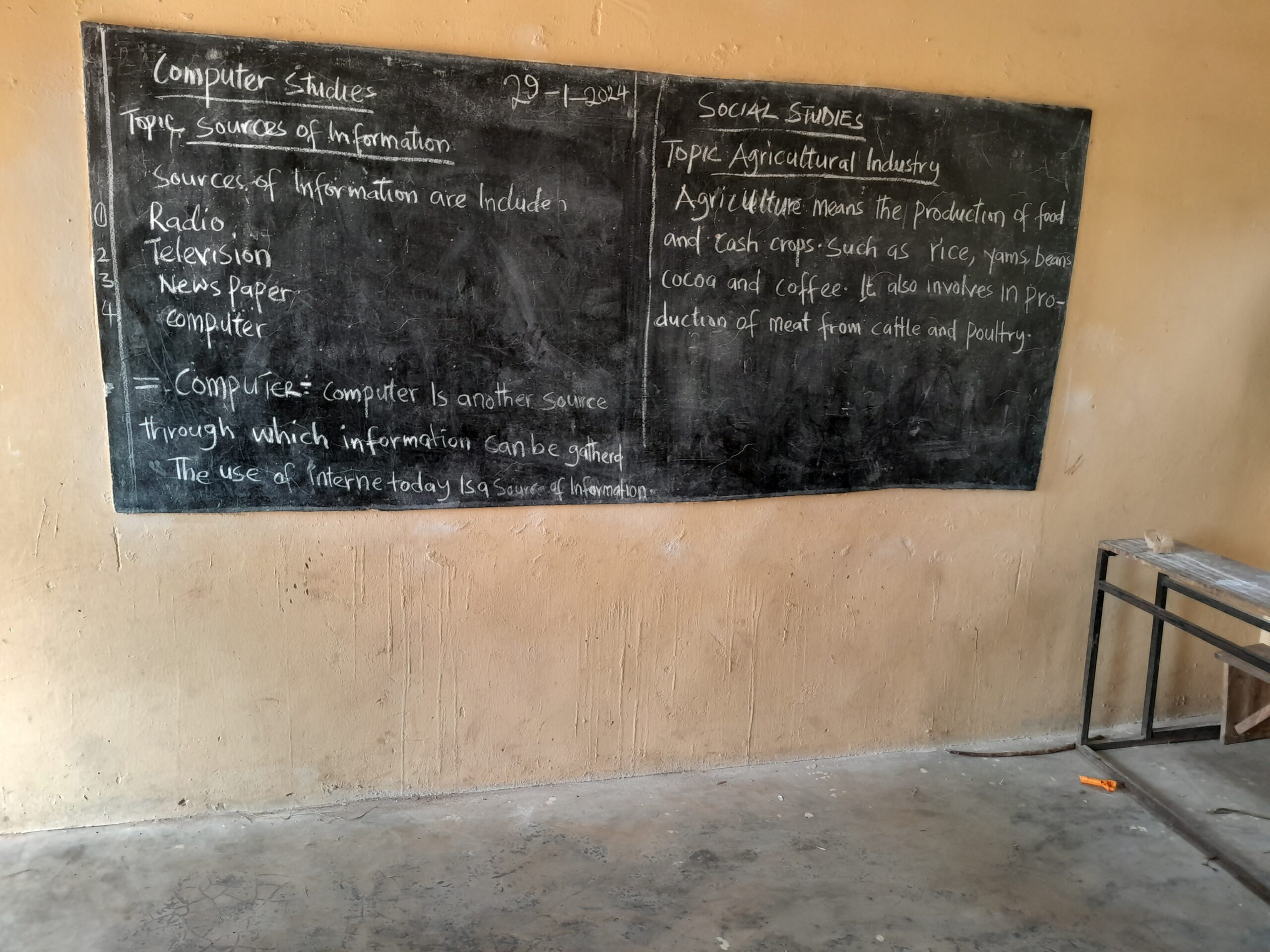

Abdullahi is one of two teachers with broad knowledge in various subjects such as social studies, mathematics, English, agricultural science, civic education, and basic science.

He excused himself and afterwards led me into an adjoining room that served as the staff office. Afterwards, he delved into his experience at the school.

Abdullahi recounted the story of a young Fulani girl named Ladifa Lawal who approached him after school hours. “She confided in me that her family initially resisted sending her to school, believing girls were better suited for housework. But Ladifa was determined to learn, and so I went to the house myself to convince them to enroll her in the school.”

Today, Ladifa is one of the top students in arithmetics and basic science, who looks forward to becoming a nurse.

Abbas is one of Adamu’s 4 children enrolled in the school. Quick on the uptake, the 7-year-old aspires to be an engineer, after his teacher told him that he could become anything he wished to be in life.

“My favourite subject is mathematics, and I’m happy to learn new things every day here,” he said to me with glee.

After the school bell rang, I waited until the school’s closing before the children led me to their parents. At Ladifa’s house, I met her mother, Husseina, who was delighted about the new developments in their community.

“Neither I nor my husband ever went to school,” Husseina said. “In fact, none of my family did. Initially, I didn’t support the idea of allowing my daughter to enrol in school, but seeing progress from other children, I gave my blessings to see her get an education. Things are now changing for the better in our community.”

Abdullahi highlighted the vital role the school is playing in transforming the lives of Fulani children in Garin Buba, equipping them with the requisite education to pursue their dreams and contribute meaningfully to their community in the coming years.

With a broad smile across his face, Abdullahi leaned back in his chair. Although his modest monthly stipend helped to keep him afloat, his greater delight was seeing these children learn something that could shape their future for good. “This feels more like community service than a job,” the 49-year-old said.

In an earlier report, Prime Progress documented the water scarcity plaguing the Garin Buba community amid neglect by authorities.

Seeing the light

In the remote settlement of Garin Yau, FUDECO Gashaka built two classrooms and named it Alhaji Yau Nomadic School. Today, it’s serving as the sole source of education for over 50 enrolled children.

On the morning of my visit, the children were engrossed in a lesson led by Malam Umar, the school’s only teacher. Yau himself had graciously accompanied me to the building, and I seized the chance to chat with some of the students.

Rukayya Adamu is one of those students who can now confidently identify and name all parts of her body, from head to toe, in English. Yusuf Sha’ibu, another student, displayed remarkable mastery of numbers, as he flawlessly recited 1 to 100.

“Educating the girl child is paramount,” said Fadimatu Abdullahi, the woman leader of FUDECO Gashaka. She stated that often girl child education is overlooked because community leaders and parents forget that when girls are equipped with the right knowledge and skills, they can grow to become agents of change in their families and communities.

“At FUDECO Gashaka, we strive for gender inclusion, that’s why we work to see that girls are also enrolled in schools while maintaining our religious and cultural values. We are now more than excited to see girls like Rukayya and Ladifa excelling in their classes, proving that they are just as capable as boys,” she told me during a conversation at the FUDECO Gashaka office.

Yau also facilitated my meeting with Yusuf’s father, Sha’ibu, who expressed his heartfelt gratitude for the new educational opportunities.

“Our children can now speak and write English, unlike us,” he told me while smiling. “Thanks to FUDECO Gashaka for what they are doing. May God bless their work. It was unfamiliar at first, but our leaders assured us it would benefit the children, and we are already seeing the results.”

Urban Fulani communities aren’t left behind

In the heart of bustling Serti town, there are tens of Fulani children who, despite living in urban communities, couldn’t afford to pay their school fees. But with FUDECO Gashaka, their dreams aren’t on hold as the organization takes on the responsibility of paying their school fees each academic term.

On a Wednesday morning, I visited a private school in Serti town named Minat Memorial School, with more than 20 learners enrolled, including 9-year-old Aisha Abdullahi Ardo, with a stellar academic record. Aisha received a scholarship, funded by FUDECO’s national leaders, all the way to university.

FUDECO Gashaka’s impact stretched far beyond Ardo’s story. Across the rural communities of Gashaka, including Garin Buba and Garin Yau, they established seven schools, imparting knowledge to around 1,000 pastoralist children.

With donations from FUDECO’s national leaders, the schools are supported with notebooks, textbooks, pencils, and football for sports. Most important, these donations ensure that teachers also receive their salaries early to enhance their morale.

These commitments weren’t limited to rural areas. Within Serti town itself, like Ardo, other 67 students in both public and private schools continue to benefit from these scholarships and free reading and writing materials.

The National Commission for Nomadic Education (NCNE), established in 2004, has significantly expanded educational access for Nigeria’s nomadic communities. Between 2016 and 2022, pupil enrollment soared from 590,511 to 1,570,983. In the same vein, the number of teachers nearly doubled, from 14,936 to 26,660, during the same period. This growth extends to the number of nomadic schools catering to pastoralists, migrant fisherfolk, and migrant farmers, which have tripled to 7,314 from 3,611.

While these statistics underscore the NCNE’s progress in reaching nomadic populations, some rural communities like Garin Buba and Garin Yau have not experienced similar success—before the advent of FUDECO Gashaka at least.

Similar initiatives are taking root across Nigeria. One such example is a school in Borno State that primarily targets Fulani children displaced by Boko Haram and provides them with education despite their nomadic lifestyle.

Challenges persist

Even before entering Garin Buba Community Primary School, Adamu mentioned a lack of chairs and tables. He bemoaned the limited supply of furniture.

“We need more help, not just from FUDECO, but we also urge the government to step in as well,” Adamu pleaded.

Abdullahi, the teacher, added that limited staff hindered academic progress in the school, as he and the other teacher struggled to manage the large number of students. “We need more classrooms with tables and chairs,” he stressed.

While Alhaji Yau Nomadic School in Garin Yau faces a similar shortage in classroom furniture, their most pressing issue is finding reliable teachers.

“We only have Malam Umar,” Yau explained. “Other teachers haven’t stayed long because living in such a remote area is difficult.” Nevertheless, Yau remains hopeful that future generations will provide more teachers from their own communities.

Yau also brought up the challenge that the new emphasis on education places an obstacle on the herding aspect, which is their way of life.

“While we appreciate the importance of education for our children, it’s becoming difficult to find people to herd the cattle, now that the children are going to school. We, the older generation, are getting tired, and the children no longer have enough time to learn the skill,” Yau said, adding that sometimes they have to travel far distances to find people that can help them.

FUDECO Gashaka, on the other hand, acknowledged challenges in accessing these communities as a result of poor roads. “Some villages are far from Serti,” said Ali Yobi, the organization’s secretary. “We use motorcycles, but it’s always tough. During rainy seasons, the bad roads leave us stranded or unable to cross small rivers, since there are no bridges.”

Limited funding also cramps FUDECO’s capacity to erect more schools. But the organization is working hard to expand its work. “We want to build more classrooms and even secondary schools so children don’t have to travel to other towns after primary school,” said chairman Bello.

One harmattan morning, I met Saidu Adamu, a 47-year-old cattle herder with intricate tribal marks, under a mango tree. Adamu, who only attended a Qur'anic learning center as a child, grew up in Garin Buba, Central Taraba State, knowing only cattle herding passed down by his ancestors.

Later, I visited Garin Yau and met Alhaji Yau Hassan, a 50-year-old who also had religious education and completed a pilgrimage to Makkah. Yau was the first to settle in Garin Yau, where residents are all Fulani and primarily herders without formal education.

In 2021, the Fulɓe Development and Cultural Organisation (FUDECO), founded in 2017, began influencing these communities, promoting the blend of traditional skills and modern education. FUDECO aims to empower pastoralists with access to essential services and education, adapt to climate change, and participate in decision-making.

Through FUDECO, Adamu and Yau now see the value of formal education and have enrolled their children in schools established by the organization. FUDECO started classes under trees with volunteer teachers and eventually built classrooms, despite initial resistance from community leaders. Their efforts include engaging in participatory research and humanitarian aid to enhance pastoralism to modern standards.

The organization has established seven schools across rural Gashaka, providing education to around 1,000 pastoralist children and offering financial support and learning materials. However, challenges such as the lack of classroom furniture, teachers, and infrastructure persist.

Despite adversities including poor road access and limited funding, FUDECO's mission is expanding, with plans to build more classrooms and even secondary schools. The efforts are showing promising results as children like Abbas Adamu aspire to become engineers, while others excelled academically, reflecting a transformative change in these communities.