When Blessing Bassey saw her menses for the first time at age 12, she was confused and thought she would bleed to death. And it did not help that her mother did not know enough to give her accurate and unbiased information and the assurance she needed about menstruation.

“My mother told me to stay away from boys, especially during my menses, and that I was going to get pregnant if I did not,” Bassey said.

She became more scared when her classmate who saw her period in school became a laughingstock.

“She was treated [by other students] like she killed someone and was called a dirty girl,” Bassey said, adding that the shaming made her classmate “stop coming to school.”

There and then, Bassey decided that she would skip school on the days she was on her period.

Sadly, the not-too-helpful words from her mother (who later gave her money to buy pads) and her classmate’s experience were the only menstruation-related discussions she had until she met volunteers from Brencare Foundation in 2021.

Period Poverty in Nigeria

An estimated 25%of women and girls in Nigeria suffer from period poverty – a lack of access to menstrual education and products like pads, menstrual cups, toilets, handwashing facilities, and others. This leads to an inability to manage menstruation with dignity, significantly impacting their health, education, and social well-being.

Chiefly responsible for period poverty in Nigeria includes the rising cost of menstrual products like sanitary pads, now selling for N700($1) in a country where most citizens live on less than $2 a day.

But a lack of awareness around menstrual hygiene contributes to period poverty, with many women and girls in rural communities using unhygienic materials, such as rags, newspapers, toilet tissues, or leaves, to manage their periods.

In addition, menstruation is often seen as a taboo subject in Nigeria, and this has made it difficult for women and girls to talk about their periods, as doing so could make others stigmatise them.

A safe space

Brenda Effiom was fortunate to have come from an educated family where her parents gave her the necessary menstrual hygiene education and support she needed as a teenager living in Calabar.

But when the family later relocated from Calabar to her rural community in Akpabuyo Local Government Area, she observed that unlike in Calabar, most girls in her community, including new friends and neighbours, lacked primary sexual and menstrual hygiene education.

“I was just seeing my mates, friends, and neighbours living anyhow. While I made informed decisions, these persons weren’t making informed decisions, and I saw a lot of unplanned pregnancies,” she said.

Effiom was about 14 years old, and she started volunteering to teach other girls how to manage their menstruation and make better sexual decisions. This initial effort opened her eyes to an even bigger problem: “Young girls were reserved and shied away about their issues, so we decided to expand,” she said.

But she did not expand until 2016, when she started the Brencare Foundation as a nonprofit, a year after she graduated from the university, to build the confidence of school girls to handle their menstruation.

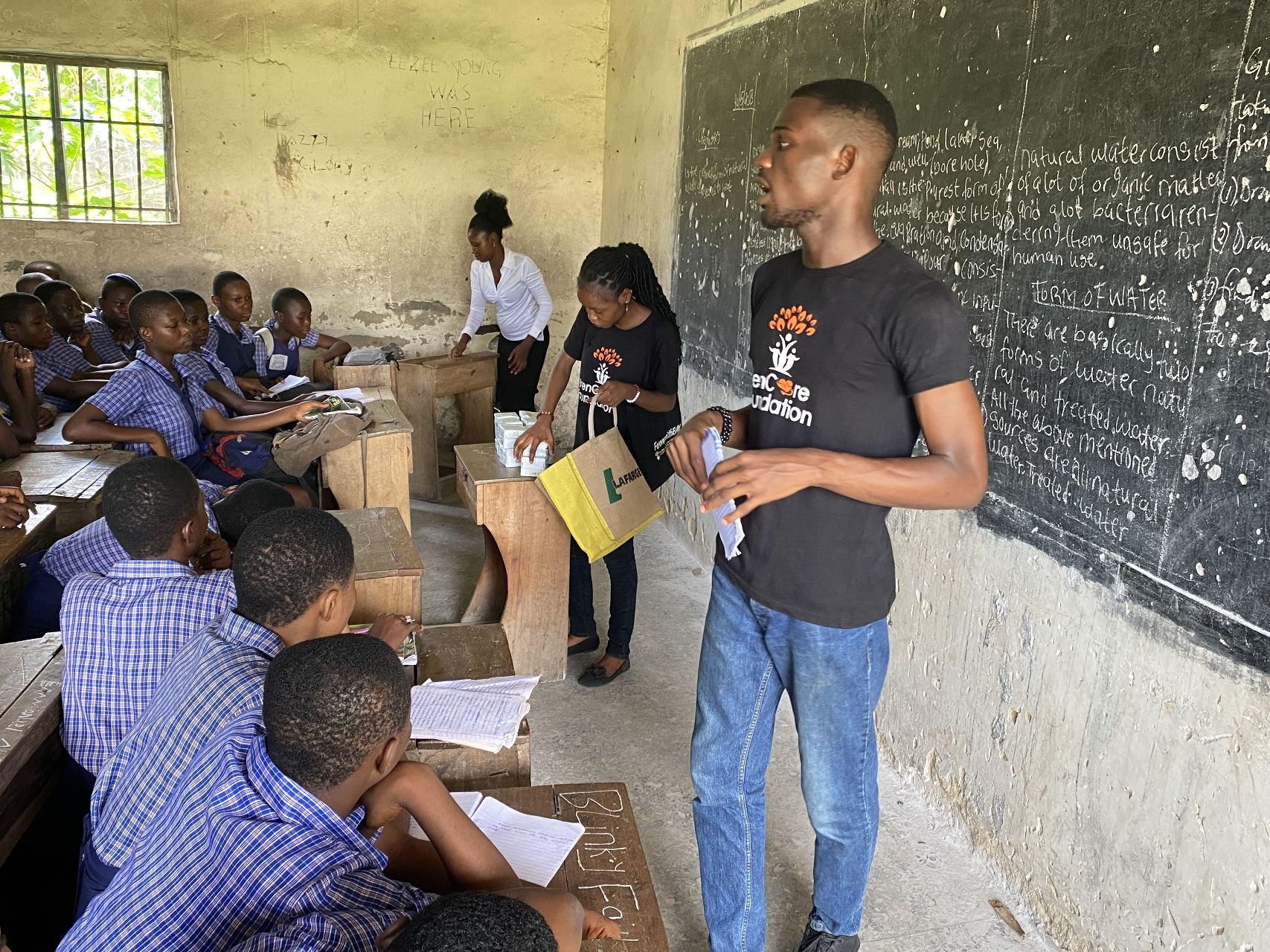

Brencare Foundation uses its safe space project to impart menstrual health and hygiene and sexual and gender-based violence education to secondary school girls and inspire them to be ambassadors to their peers and parents about menses.

Volunteers from the foundation visit the schools once every week and hold meetings called safe spaces where the girls are free to express themselves and talk about everything. The sessions take place in secluded places within the schools.

“Most girls have their first period in school where they build habits and are vulnerable. So [the schools are the best place] to meet them with this intervention,” said Rachel Idim, the foundation’s program manager.

“Schools are usually one of the worst places for adolescent girls, as they can be bullied about their menses, even by teachers, some who don’t even know these things.”

Initially, the girls refused to open up, “and it was understandable,” Idum said, “but by showing up consistently and starting with basic lessons on how to keep oneself clean, they got fully involved and led some sessions themselves.”

While BrenCare Foundation sometimes distributes sanitary pads to the girls, the safe space project focuses more on menstrual health, hygiene and reproductive health education.

Brencare says it has reached about 5000 women and girls across communities in Cross River State with menstrual health and hygiene and sexual and gender-based violence or SGBV education, with the safe space project reaching almost 200 female students of Government Secondary School, Lagos Street; and Government Secondary School, Akim; both in Calabar, the state capital.

But while the grant-dependent project has built the girls’ confidence with gender and sexual-based violence and SRHR information, it has not always been smooth sailing.

Caesar Amoikwen, communication lead at the foundation, said on some days, some school teachers are unnecessarily hostile towards the team because they feel the nonprofit fronts the girls to attract grant money for personal use.

Also, the foundation is run mainly by university undergraduate volunteers whose study schedules sometimes clash with the time for the safe space meetings.

Despite the challenges, Grace Asuquo, a student at Government Secondary School, Akim, said the lessons have been valuable. “As a first child, I can talk to my sister about menstruation and general hygiene. I have the knowledge now,” she said.

And Bassey described the safe space as one of the best “classes” she attended in the school. “I always looked forward to the games and the experience sharing. And thanks to the lessons they shared, I know my body better now.”

This story was produced with the support of Nigeria Health Watch through the Solutions Journalism Network, a nonprofit organisation dedicated to rigorous and compelling reporting about responses to social problems.

Blessing Bassey experienced confusion and fear when she had her first menstruation at age 12 due to a lack of proper information and support from her mother. Her fear was exacerbated by the stigma and bullying faced by a classmate at school, prompting her to skip school during her periods. This highlights the issue of period poverty in Nigeria, affecting 25% of women and girls who lack access to menstrual education and products.

Rising costs of menstrual products and inadequate awareness about menstrual hygiene contribute significantly to period poverty. Many girls resort to using unhygienic materials, and the stigma around discussing menstruation further complicates the issue. Brenda Effiom, motivated by her own informed upbringing, founded Brencare Foundation in 2016 to address these challenges by providing menstrual health education and creating safe spaces for girls to discuss their experiences.

The foundation conducts weekly sessions at schools, offering girls a platform to openly talk about menstrual health and hygiene. The initiative has reached about 5000 women and girls in Cross River State, providing essential education and confidence. Despite facing challenges like suspicion from teachers and scheduling conflicts with volunteer commitments, the project significantly benefits participants by empowering them with knowledge and support.

This story was supported by Nigeria Health Watch and the Solutions Journalism Network, emphasizing the importance of addressing social problems through informed reporting.