IKOYI, LAGOS: The time was 7 am one Wednesday in November 2018. Raphael Jinias received a call from his boss at Stylezone Limited, a firm providing massaging services in Lagos. His boss instructed him to report at the office that morning.

But, “it was [supposed to be] my off day,” said the 30-year-old who worked as a security guard at Stylezone Limited.

Jinias is from the core northern state of Adamawa. He had left his poor and struggling father in Adamawa and came to Lagos to work and raise money for his university education shortly after his mother died in April 2017.

When Jinias arrived at the office, his colleagues informed him that a burglar had broken into the firm’s accounts office and carted away items and cash. Jinias’ boss accused him and three stylists at the firm of being the perpetrators.

His boss consequently called the police and had him and the others arrested, even after a police-led search of his (Jinia’s) home failed to prove he was a culprit.

At Ifako Police Station in Gbagada, the stylists were released on bail. But the police, at Jinias’ boss’s request, insisted Jinias face trial as the alleged main suspect.

On the first appearance at Ogudu Magistrate Court that November, the case was adjourned because Jinias had no legal representative, and he could not afford one. So from there, he was transferred to Ikoyi prison to await trial.

“Awaiting trial is a term used mainly for those [already] in prison [but not convicted],” said Sunday Ajibo, coordinator of the Enugu State branch of Legal Aid Council of Nigeria, a government body providing legal support to accused persons who cannot afford the cost of hiring a lawyer. “If you start calculating the period of awaiting trial, you have to start calculating from the time of the arrest.”

Sadly, about 74.8% of Nigeria’s total prison population is still awaiting trial. Despite that most Nigerian prisons are overcrowded, the average time those awaiting trial spend in jail is three to seven years.

In Lagos, there are 8,000 inmates in five correctional facilities. Of those, 6,800 are still awaiting trial. Spending months or years awaiting trial than the sentence for the crime itself contravenes the legal protections guaranteed in the Nigerian constitution.

Factors responsible for this delayed justice administration here include repeated adjournments and unnecessary delays in court proceedings by judges, failure of the police to produce accused persons in court, an accused person’s failure to present a legal representative, missing files, and delays in the issuance of certified true copies of court judgments.

Freedom for Jinias

But from where he least expected, help came for Jinias the same month he was taken to Ikoyi prison. Two lawyers from Headfort Chambers, a Lagos-based law firm with a corporate social responsibility department (CSR) offering free legal services to inmates awaiting trial, visited Ikoyi prison to take up poor inmates’ cases.

On arrival, prison officials called out some inmates to meet the lawyers.

Before the pro bono lawyers take up any case, the inmate must meet all conditions: Must be a pre-trial detainee, charged for a minor offence, wrongly incarcerated and without legal representation. Jinas met the requirements, so the lawyers took up his case, among others.

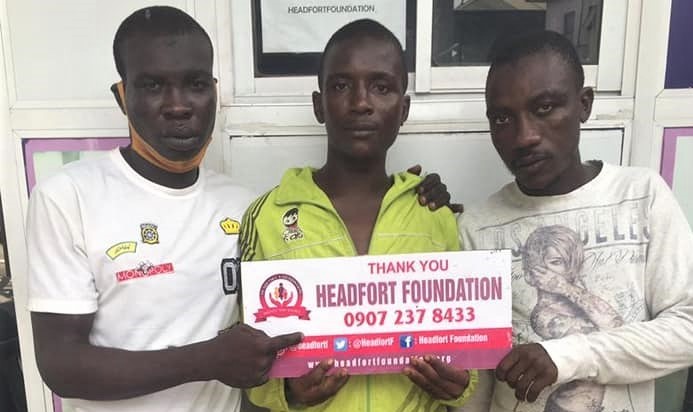

A lawyer assigned by Headfort Chambers to handle his case began by first investigating the matter further. When the case came up in January 2019 at Ogudu Magistrate Court, the lawyer made his first appearance for Jinias, but the case was adjourned a second time because the complainant (Jinias’ boss) did not appear in court. When he failed to appear the fourth time in October 2019, the judge dismissed the case, and Jinias was freed.

“I felt bad when I was taken to the prison. I even asked God why ‘should I be suffering from something I know nothing about,”‘ Jinias recalled. “If not for Headfort, I will still be waiting for trial in prison.”

Usually, Headford Chambers empowers inmates and helps them reintegrate into society after successfully securing their release from the prison. It could be helping some get a skill or start a small business. But Jinias wanted to further his education, so the firm paid for his Joint Admissions and Matriculation Board (JAMB) examination form, an assessment examination for securing admission into the university in Nigeria. It also promised to support his education.

Headfort Foundation

Oluyemi Orija was called to the Nigerian Bar in 2013. Between then and 2015, she worked for three different private law firms. During her time with the firms, she had experiences that left her wanting to provide free legal services to poor inmates.

“I had the opportunity of appearing in court on a daily basis. I witnessed [some] inmates being brought to court for minor offences,” the human rights advocate said. “[Some] had spent months and years in prison for frivolous charges trumped-up by the investigating police officers. The inmates remained in prison simply because they could not afford to contract the services of lawyers.”

She said, “at the time, I could not represent them because of the contract of employment I had with my employers, [but] I determined that once I started my private practice; I would [add] free legal representation of indigent inmates as a corporate social responsibility.”

That dream came to pass in 2015 when she established Headfort Chambers and later introduced pro bono legal service to the firm in 2018.

But as calls from people requesting free legal support increased, Orija soon realised her initial plan to provide pro bono services as CSR would not accommodate many people.

She needed to expand, so she registered the Headfort Foundation as a nonprofit and transferred the chamber’s pro bono structures to the foundation.

When it launched in March 2019, it started with seven staff; now, it has 15, including eight all-female lawyers who help secure the release of inmates awaiting trial. It also has dozens of volunteers. Since then, it has helped about 200 inmates regain freedom.

These days, the nonprofit educates people on their fundamental human rights via its Instagram live stream (@headfortfoundation) every Saturday by 7 pm. To reach more people, it launched a mobile application called “Lawyers NowNow” after the #EndSARS protest of October 2020 against police brutality across the country. The app connects users who need free legal support with pro-bono lawyers nearest to them.

But corruption in the judicial system sometimes frustrates the non-governmental organisation’s (NGO) effort to provide free legal support unhindered.

“We are doing the work that we are not being paid for. Yet, officials of the judiciary need us to tip them before they do their job,” Orija said. “When we let them know that we are pro bono lawyers, they will tell us that we are doing pro bono work because we are rich; hence, we should tip them.”

Orija said the group’s funding comes from Heartfort Chambers and from “individual persons who believe in our vision [and support us] through donations.”

She said her ultimate goal is for everyone in Nigeria to gain easy and free access to justice regardless of social and economic status.

Now, Jinias works as a bartender at Orange Exclusive Lounge (a club and bar) in Lagos while waiting for university admission to study his dream course. He did not pass his previous JAMB examinations, and he plans to retake the test this year.

“I wish to study engineering,” he said. “Headfort has promised to sponsor my [university] education. I am happy.”

Besides Headfort Foundation, there are other local groups working to improve the administration of justice in Nigeria, including supporting pre-trial inmates, such as The Rights Enforcement and Public Law Centre or REPLACE, Just Empower Initiative, and the Legal Aid Council of Nigeria.

IKOYI, LAGOS: In November 2018, Raphael Jinias, a 30-year-old security guard at Stylezone Limited in Lagos, was called to work on his off day. Upon arrival, he was accused of burglary along with three stylists and arrested after a police search yielded no evidence against him. At Ifako Police Station, the stylists were released on bail, but Jinias was forced to await trial in Ikoyi prison for lacking legal representation. About 74.8% of Nigeria’s prison population, like Jinias, awaits trial often for years due to judicial inefficiencies.

Help came for Jinias when two pro bono lawyers from Headfort Chambers, a Lagos law firm, took up his case. The lawyer's investigation led to the case being dismissed in October 2019 after the complainant, Jinias’s boss, repeatedly failed to appear in court. Headfort Chambers not only secured his release but also supported his educational aspirations by funding his examination for university admission.

Oluyemi Orija, the founder of Headfort Chambers, established the Headfort Foundation in 2018 to provide free legal services to indigent inmates. The foundation has since expanded, helping around 200 inmates regain their freedom and educating the public about legal rights. Despite challenges like judicial corruption, the foundation aims to ensure everyone in Nigeria has access to justice regardless of their socio-economic status. Raphael Jinias now works as a bartender while awaiting university admission, with Headfort Foundation committed to sponsoring his education.