IBADAN, OYO: What would become the beginning of years of depression and repeated attempts to end her own life began in May 2011.

At about 7:45 pm on a particular Sunday that month, Blessing was walking home after she closed from a computer training centre where she was taking a course in general computer operation in Ibadan, Oyo State.

Midway, in one of the dark and sometimes lonely neighbourhoods of the ancient city, she felt a heavy hand cover her mouth tightly from behind, even as the assailant held her firmly by the torso with his other hand.

She struggled to rip herself off his grip to no avail. Then, within minutes, it was over. He had raped and left Blessing on the ground, crying and traumatised.

Weeks later, Blessing, who was 20 years old then, discovered that that single act had resulted in a pregnancy. Then her life took a sudden depressing twist.

“How do I explain to people that I got pregnant for someone I don’t even know?” the 30-year-old recalls herself lamenting. “[So] I attempted suicide three times.”

She managed to keep the pregnancy and later gave birth to a baby boy with her parents’ support, but the trauma and depression lingered with her years after childbirth.

At least one in every three women in the world aged between 15 and 49 has experienced one form of sexual and gender-based violence (SGBV), especially from intimate partners, the World Health Organisation or WHO says.

Similarly, 30% of Nigerian women and girls within that age bracket have been victims of SGBV. The WHO says 42% of abused women have an increased tendency to commit homicide or suicide, acquire infections like HIV, and develop physical, mental, sexual, or reproductive health injuries.

Yet, nearly 50% of victims never speak up or seek justice. This is due to fear of stigmatisation, intimidation, and threats from the perpetrators, said Adeola Oladimeji, secretary of the International Federation of Women Lawyers in Oyo State.

“We don’t really have a civilised society that understands that crime should be punished and victims should not be labelled,” Oladimeji said, referring to Nigeria. “Until when people know that being a victim of any crime does not define you, we will not get people coming out to get justice for themselves because the shame and stigmatisation are there.”

Several Nigerian laws prohibit all forms of gender-based violence, including the Violence Against Persons Prohibition Act that stipulates life imprisonment for rapists and a maximum of 20-year jail term (without a fine option) for offenders of other gender-based crimes like female genital mutilation.

But since it came to effect, only 18 of the country’s 36 states have adopted and domesticated it, with most of them being conservative northern Nigerian states. Even in states where it has been adopted, no conviction has been recorded due to weak implementation.

Oladimeji attributes some states’ unwillingness to either domesticate or implement the law fully to factors like poor female representation in state legislative assemblies. She said since women are mostly victims of SGBV, poor female representation means fewer women pushing for the law’s adoption. She said some male lawmakers across the states are reluctant to support its adoption because they sometimes violate the law and are afraid it could cash up with them.

Thanks to ‘Safe House’

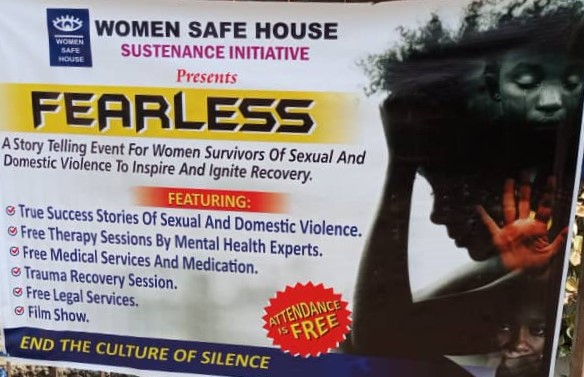

About five years after the rape, in September 2016, Blessing’s friend invited her to attend a book review programme in Ibadan. During the event, which centred on the impact of SGBV, one of the speakers, Wuraoluwa Ayodele, explained how victims could recover. That “how” included her introducing “Safe House” as a place in Ibadan where victims receive rehabilitation.

Provided by Women Safe House – a nonprofit Ayodele founded, “Safe House is a [free] shelter space where women can come in temporarily away from their abusers or perpetrators of violence” to recover psychologically, mentally, and emotionally before returning to their homes, Ayodele said.

Blessing approached Ayodele after the event, shared her experience, and inquired more about the shelter.

“I felt [like] she was the best person I could speak with because I was still confused,” she said.

A week later, Blessing arrived at Safe House and was ushered into a big room she shared with three other women. Few days after arrival, she began a six-month rehabilitation programme that required her to spend the first three weeks at the facility and the rest of the rehabilitation time in her home.

The rehabilitation included private counselling sessions with a mental health expert and group activities with other victims and survivors.

The private sessions mainly were non-medical therapies involving teachings on how to keep her private environment free of colours, sounds, paintings, and pictures that could remind her of the rape; how to maintain good sleeping positions to avoid nightmares; and how to avoid thoughts that might make her relive the violent event.

During daily group activities, each woman shared her experience with other women, listened to theirs, and wrote down her positive experiences in a “gratitude journal” to help her stay grateful for the good things that had happened for her and not dwell on the negative.

“Sometimes they don’t actually need medication; everything is not medication-based. They just go through these things, and they are able to get over their experience,” said Ayodele. “And having a network of other women who have gone through the same thing, they see that ‘I’m not just the only person going through it, I am not crazy.’”

True enough, by the time Blessing completed her three-week stay, she had improved significantly.

“My experience was painful. When I came in (to Safe House), I was chattered and depressed,” Blessing said. I went through some psychology sessions, was taught how to regain my self-confidence, and I recovered.”

Why Safe House?

Ayodele grew up as a child watching her mother suffer abuse at the hands of her father. Her mother sometimes wished she could get respite somewhere away from home. This motivated Ayodele, a legal practitioner, to start Safe House in 2016.

“One of the primary needs of women facing violence is having a safe place to go to and stay for a while until they can get back on their feet,” the 30-year-old said.

The two-bedroom sanctuary is kept secret from the public for the women’s safety. And because it can only accommodate six women per time, each woman is allowed to stay only for three weeks so that another set can come in.

But Women Safe House also delivers the same rehabilitation sessions to women at the homes of some of its network of 50 volunteers.

With support from groups like The Pollination Project, International Centre for Women Playwright, and Afrab-Chem – a pharmaceutical company in Nigeria – Safe House has rehabilitated about 3,000 women and girls since 2016. It feeds those at the facility twice daily and provides them with health support and other essentials like sanitary pads.

It regularly takes awareness programmes to public places like churches and markets to educate women and men about the danger of SGBV.

To protect itself from possible accusations of abduction, it registers each case with the police. It makes sure every admitted woman signs a consent form acknowledging that she came to the facility without force.

The women, who must provide at least one piece of evidence of abuse (pictures, third-party testimonies, a doctor’s report, and audio or video recordings) before admission, also promise never to bring their abusers or stranger to the facility.

For the women who have no jobs, wish to start small businesses but have no funds, Safe House offers them small interest-free loads (not more than N100,000 or $247).

“The loan N10 000 ($24) I received was for my popcorn business,” said 37-year-old Busayo Ilori who, who came to Safe House in June 2019 after suffering physical violence from her husband. “It is really helping me because I get daily income that helps me feed my [four] kids.”

For Blessing, she had learned tailoring years before coming to Safe House. With Ayodele’s encouragement, when she returned home from Safe House in March 2019, she took a job as a casual worker in an agricultural firm in Ibadan. Months later, she had saved enough to buy a sewing machine with which she started her fashion business from her home.

The business has since grown with five female apprentices and one staff. From it, she trains her son. “Today, I am fulfilled. I am comfortable with what I am doing,” she said.

Ayodele said her challenge is that some women easily submit to pressure from their relatives to return homes (where they are abused) even when they have not fully healed. She said, sometimes, the women return within a short time after leaving the facility with the same abuse complaint.

She also said that lack of adequate funding prevents the group from renting and moving into a bigger facility that can accommodate more women per time.

Meanwhile, Blessing said the recovery she received through the sanctuary is one she would always be grateful for.

“The best gift one can have is to have good people around. I am glad I met her [Ayodele],” she said.

In May 2011, Blessing was raped while walking home in Ibadan, Nigeria, leading to a pregnancy that caused years of depression and suicide attempts. She managed to keep the pregnancy with her parents’ support but continued to struggle with trauma. Statistics indicate that one in three women worldwide aged 15-49 experiences sexual and gender-based violence (SGBV), with similar situations in Nigeria where many victims remain silent due to fear of stigmatization.

Nigerian laws, like the Violence Against Persons Prohibition Act, aim to protect against SGBV, but poor implementation and low female legislative representation hinder their effectiveness. Blessing later found support at "Safe House," a rehabilitation center founded by Wuraoluwa Ayodele, which provides temporary shelter and counseling to SGBV victims.

Safe House offers rehabilitation through therapy, group activities, and sometimes interest-free loans to help women start small businesses. Since 2016, it has helped about 3,000 women and girls. However, challenges remain, such as women prematurely returning to abusive environments due to familial pressures and a lack of adequate funding for the facility.

Blessing has since successfully started a fashion business and feels fulfilled, attributing her recovery to the support from Safe House and its founder, Ayodele.