By Nanji Nandang

Plateau State, Nigeria—Mary Yakubu* headed home as dusk settled, her small frame weighed down by fatigue. Her feet were coated with dust, and her face bore traces of weariness after hours of walking and calling out to passersby.

Her tray, nearly as big as her, was still heavy with unsold kununzaki (a popular non-alcoholic drink made from millet)—a bitter reminder of the day’s toil.

The familiar sounds of children laughing and playing nearby reminded her of the school she only dreamed of attending. Her eyes, filled with longing, glanced briefly at the children before turning back to the road that led her home.

The six-year-old arrived to find her older brother, Henry Yakubu, along with two of his friends, in the cramped single “face-me-I-face-you” room where her mother and three siblings all lived.

Since the death of her husband six years ago, Mary’s mother had slipped into a life of neglect and debauchery. Often drunk, she could only provide little care for her children, leaving them to fend for themselves.

Mary, her youngest child, supported her paternal grandmother with hawking kununzaki in the streets of Plateau State, where a consistent pattern of child labour exists across all age categories.

“My mother and older siblings are not usually home at that time. I told my brother I was hungry,” she said.

Henry told his sister to pull off her clothes and let his friends play with her first, the same game he’d introduced a few months earlier, promising he would buy her noodles afterwards.

The 15-year-old had begun defiling his sister months earlier, later involving his friends. Mary’s life took a different turn when male neighbours started demanding sex from her in exchange for food.

One evening in August 2022, Mary confided in Madam Rose, a neighbour, about how another elderly neighbour had assaulted her, resulting in her limping. Soon afterwards, Madam Rose called the Christian Women for Excellence and Empowerment in Nigerian Society (CWEENS) helpline to report Mary’s case.

“That was how I came to CWEENS shelter and my brother was arrested. I was brought to Kamkpe house.” Mary recounted.

“CWEENS is a child of circumstances,” said Oluwafumilayo Para-Mallam, who founded CWEENS, “because women were weary of the incessant killings of women and children during the ethno-religious crisis that bedevilled Plateau State between 2008 and 2010.”

Para-Mallam, who coordinates the national affairs of the organisation, explained that she collaborated with a few women to write a communique to the state government highlighting some of the critical issues for action and by leading women to act and express their concerns.

“We started out as a group of six women and started a 21-day fast and then a massive peaceful protest tagged ‘Women-in-Black,’ a platform we used to call out the federal government, state government and the general public to take decisive action at ending the bloodbath across the state,” she noted.

The protest was recorded as one of the biggest protests by women in the history of Plateau State. According to her, Kamkpe was created to provide shelter and rehabilitation for women and children affected by the ethno-religious crisis in Dogo Nahawa, Plateau State, where over 150 children and 80 women were murdered. Kamkpe House alone has provided temporary accommodation, counselling, legal assistance, skills training, and free education to over 5,000 women and girls.

“CWEENS doesn’t only provide shelter for survivors,” says Dirmicit Binyir Pyentam, the program manager, “but it also provides legal and psychosocial support, empowerment programs, life skills trainings and girls mentoring schemes.”

Pyentam added that the shelter welcomes women and girls of all ages and boys from newborns up to age seven.

Para-Mallam noted that CWEENS later established an office in Nasarawa State and a shelter at the Federal Capital Territory (FCT).

“We operate across the geopolitical zones in 14 states, including the FCT. We are a network so women can join the network regardless of anything.”

Women and Girls Empowered

Mary was soon enrolled in a private school after several sessions of psychotherapy and trauma counselling.

As Mary expressed her excitement about being in school, emphasising, “I want to give back to my community by saving lives, which is why I’m studying hard to become a certified nurse someday.”

Abigail Musa had been on the verge of suicide when a friend referred her to CWEENS. The 30-year-old, who had been living with her family in Kaduna State, shared that her mother began pimping her out to older men when she turned sixteen.

“My sisters and I struggled with it, but I couldn’t bear it any longer and ran away when I turned twenty. When I reached Plateau State, I had no idea where to begin,” she recounted in a voice laced with pain.

Abigail tried small businesses and menial jobs to make ends meet, but the wages weren’t sufficient to cover her bills, plunging her into debt.

“My failed efforts left me retraumatized. It felt like nothing was working out, and I was about to give up when a friend introduced me to CWEENS,” Abigail recalled.

She said that her debts were cleared, and she was given an opportunity to improve her makeup skills. After she graduated, Abigail received a small starter pack to support her business.

“I also learnt bag-making while staying at the shelter. I sleep better at night after my sessions with the psychologist, and I feel empowered now that I have a stable source of income,” she continued.

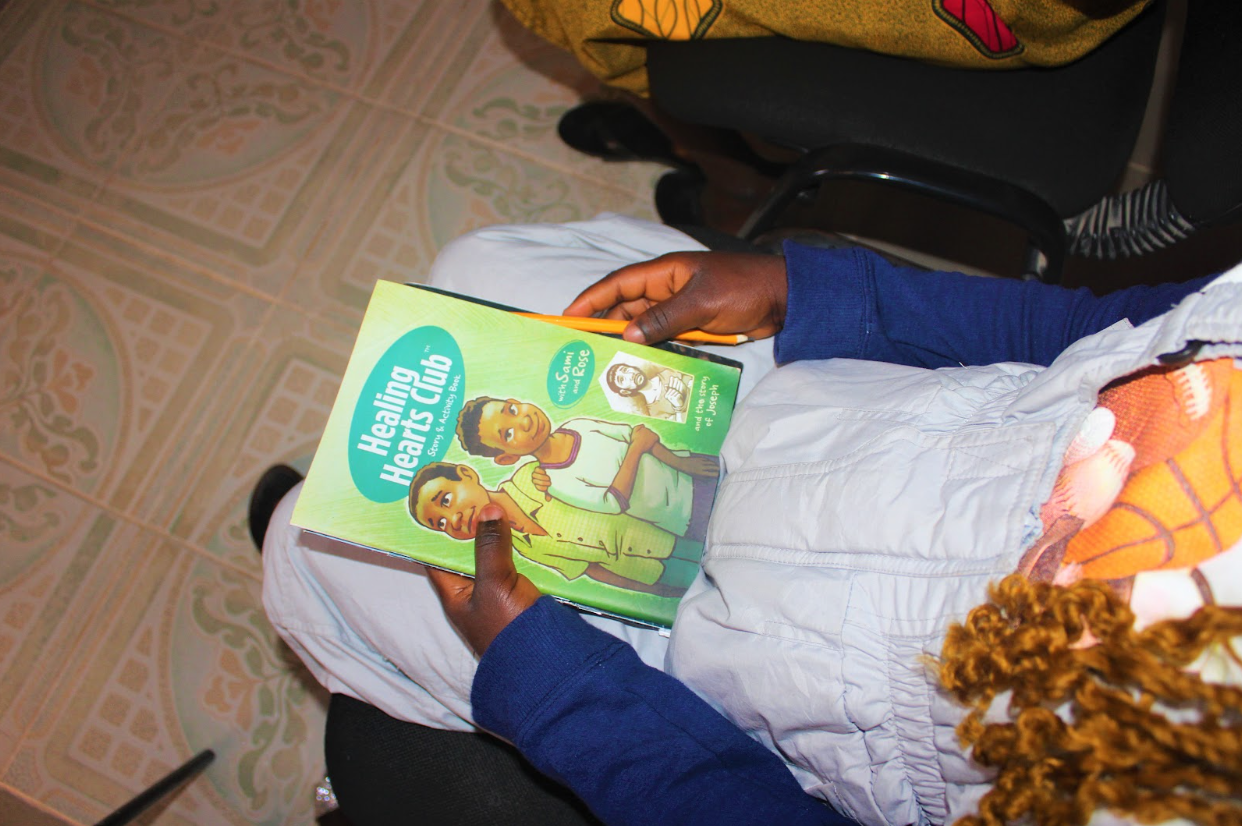

Joy Mathias*, a beneficiary of the Girls Education and Mentoring Scheme (GEMS) Club, recounts the skills she has learnt.

“Though we meet for only once a week after school hours, I have learnt about menstrual hygiene, baking, and leadership skills,” she said.

In the same vein, Mercy Luka*, a survivor of child abuse, expressed her love for baking and playing Scrabble with friends in the shelter.

*Names have been changed to protect sources’ identities.

Disclaimer: To ensure anonymity, certain elements of survivor stories may be generalised. Names, locations, identifying characteristics, or any specific details that may potentially reveal the survivor’s identity are altered or omitted deliberately.

Mary Yakubu, a six-year-old from Plateau State, Nigeria, endures child labor and abuse brought upon by her neglectful environment following her father's death. Her brother Henry exploited her for sexual acts, later including neighbors, which left Mary vulnerable and coerced into trade-offs for basic needs. When Mary confided in a neighbor about the abuse, intervention came from the Christian Women for Excellence and Empowerment in Nigerian Society (CWEENS). Founded amid the ethno-religious crisis in Plateau State, CWEENS provides support like shelter, counseling, legal aid, and education for women and children. The organization, born from women-led activism, has since expanded to 14 states, creating a network that empowers women through various programs.

In the CWEENS shelter, Mary received psychological support and the chance to pursue education, expressing her aspirations to become a nurse. Abigail Musa, another beneficiary, escaped a life of exploitation and received debt relief and skill training, empowering her to achieve financial independence. The programs at CWEENS, such as the Girls Education and Mentoring Scheme, provide survivors roles like baking and learning about leadership and hygiene, evidencing the transformative impact on participants' lives. Despite protected identities to maintain confidentiality, survivors' stories highlight the critical role CWEENS plays in providing hope and rehabilitation in the face of systemic challenges.