ENUGU: Each time Chinweotito Egwim returned home from school, she complained about how other children in her school, the McCoy Model School in Abia State, southeast Nigeria, always said she could not speak well.

“Anytime she complained, I would promise to take her to the hospital so she can speak like other children,” Chinweotito’s mother, Miriam Egwim, said outside the Good Shepherd, a private specialist hospital in Enugu.

Four years ago, Chinweotito was born with a cleft palate – an opening in the roof of the mouth that occurs when the tissues do not come together during development in the womb. But her mother did not notice it while they were at the hospital. The doctors told her everything was fine.

But each time she fed her daughter with milk, Egwim noticed it came out through her nostrils. And one day, when she cried, weeks after she was born, Egwim looked inside and saw a hole in the roof of her mouth.

“I became uncomfortable and felt it was unusual,” the 30-year-old mother said, her voice trembling. “I quickly told my mother what I had seen, and she said it was how ‘God created her.'”

A global congenital malformation

Every three minutes, a baby is born with a cleft lip or palate (upper part of the mouth) somewhere in the world. On average, one in every 500–750 live births results in a cleft- a congenital malformation of the lip, palate, or both.

The US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reports that there is no single known cause of cleft lip/palate, but a combination of complex genetic and environmental factors like smoking, alcohol consumption, and certain kinds of medication during pregnancy could increase the risk of a child being born with the defect.

Apart from speech impediments, other complications that threaten the normal living of children with cleft lip/palate include eating problems, ear infections, hearing loss, and dental problems.

While an estimated 19,000 children in Africa are born with the condition annually, about 6,186 babies are born with clefts in Nigeria every year.

The prevalence of this condition varies with regions – highest in Asian countries (1/500) and lowest in African populations (1/2500). In Africa, some babies born with it do not receive the surgery they need to correct the problem due to the perception that clefts are an evil curse and a bad omen. As a result, some babies born with this abnormality are immediately abandoned and kept away from the public.

In highly religious Nigeria, clefts are sometimes viewed as divine punishment for parental sins such as witchcraft or prostitution.

Nkeiruka Obi, program director of Smile Train in West and Central Africa, said the myth surrounding cleft had starved many families of the correct information about the condition.

She adds that poverty is another factor that has adversely affected this course, which is why early surgery may not be an option for many families in developing countries.

After noticing the opening, Egwim was now careful with how she fed her daughter, especially when she became eight months old and could eat solid food as a complement to breast milk.

She made sure to remove bones and other ingredients that could easily enter her palate and come out through her nostrils while she fed Chinweotito.

Two years later, when Chinweotito naturally should pick up increasing numbers of words and combine them into sentences, Egwim noticed that Chinweotito was having difficulty speaking.

Now, she thought it was from her tongue. But when she and her husband visited several hospitals, they were told Chinweotito’s tongue was okay.

Back at home, friends and family advised Egwim not to seek further medical attention for her daughter because the opening “will go with time.” They said she might lose her daughter if she decides to go ahead.

“Each time I took Chinweotito to the market and church, and she opened her mouth to speak, people who hardly heard what she said asked me to go and know what the problem is,” she said.

Now, Egwim was caught between two worlds- seeking medical attention or waiting for the opening to close with time. The stigma continued.

Finding a solution

In May this year, after she could not bear the pain anymore, Egwim picked up her phone and called her sister, Loveline Jorom, a midwife.

“She asked me to bring my daughter, and she examined her and asked me not to worry, that she would make inquiries,” she said.

In June, Jorom called and told her about how a patient whose son had a cleft came to the Good Shepherd Specialist Hospital where Smile Train – a nonprofit organization helping children with clefts, sponsored a free cleft surgery for her child, and he became well again.

“That was how we got to know each other,” she said. “I was afraid of the surgery. But my sister encouraged me and said other children had been doing it.” Egwim then brought Chinweotito to the Good Shepherd Hospital in July for surgery.

The surgery

Inside the theatre at the hospital on July 22, a surgical light beams over the face of Chinweotito as she is about to undergo a cleft palate repair. Ifeanyichukwu Onah, a plastic surgeon with the National Orthopaedic Hospital, Enugu, who covers the Good Shepherd on an honorary basis, had scheduled the surgery with her parents.

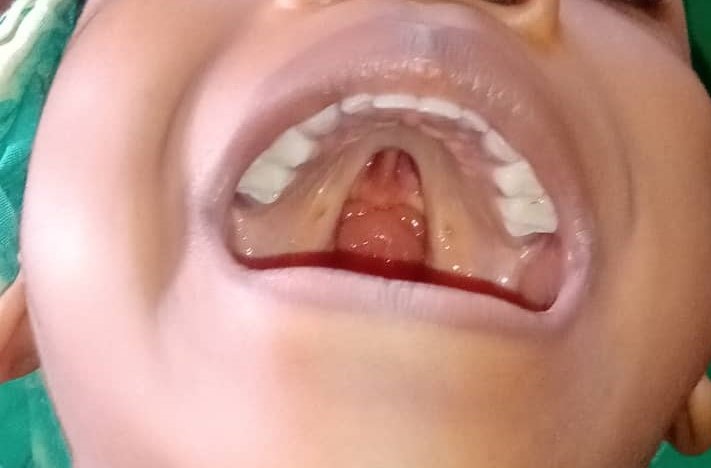

After, Chinedu Obi, a consultant anaesthetist, makes Chinweotito unconscious under general anaesthesia. Onah fits a metal device inside her mouth to keep it open.

Looking focused and undisturbed by the task before him, he requests scalpels and scissors. He begins to re-enact what was supposed to have happened before Chinweotito was born – bringing together the bits of the mouth’s roof that did not meet together and causing them to meet surgically.

He pays particular attention to the muscles that move the soft palate and tries to reposition them to mimic what children born without cleft palate have. This is so she can close her nose from the mouth when speaking and eating.

Before then, Onah had made sure Chinweotito had the appropriate weight, the normal blood count and was entirely fit for the surgery.

“Deciding to do a surgery when the weight is poor, and there is a recurring infection is extremely risky,” he said.

The surgery lasts for over two hours. Gently and precisely, Onah takes out the metal device from Egwim’s mouth and tries to keep bleeding as minimal as possible as Obi also removes the tube. Sweat balls trickle down his forehead as he makes his way out of the theatre and removes his scrub and gloves.

As she wakes up, Chinweotito begins to whimper. Gently, one of the nurses inside the theatre carries Chinweotito into the room, where her mother waits with trepidation and lays her on the bed.

As soon as she sees her daughter, Egwim smiles. Onah reassures her that her baby is in perfect condition and instructs her to make sure she does not take solid food for 21 days, so it does not affect the repair.

“She will take liquid food and multivitamins,” he said. “Once she has recovered fully and is taking food orally, we don’t expect any adverse effects.”

A speech therapist had been informed to ensure that the speech is okay after the surgery, Onah announced. When the speech therapist starts, Chinweotito will come after four weeks and have a session and go back home to continue practicing.

Onah says it is preferable to operate before the speech has formed so that the child can have the best chance of developing normal speech.

Smile Train on a mission

Onah has done about 800 cleft surgeries since 2006. Over 90 percent have been sponsored by Smile Train. He is one of the medical professionals who are being empowered to heal clefts in Nigeria.

He says he has been to Taiwan, Uganda, and other countries to attend workshops on improving his skills to carry out cleft surgeries, all sponsored by the nonprofit helping local surgeons strengthen their capacity by supporting local and international workshops.

Before Smile Train – which is headquartered in New York (US) and has an office in Lagos (Nigeria), came to the National Orthopedic Hospital, the hospital was averaging 30 surgeries a year. The cost per repair was N100,000 ($625), which many parents could not afford in a country where over 41% of the population live in extreme conditions. But now that it is free, the hospital conducts over 100 surgeries annually. Smile Train also provides transport fare for families who cannot afford it to the hospital.

“Smile Train has made it easy for patients to present themselves for surgery because it sponsors the surgery, gives transport grants, and also sponsors nutrition for those who are not at the proper weight for their age,” Onah said, adding that he considers his job an opportunity to serve humanity.

“You look at someone that looks not so normal, and when you are done with your surgery, you watch the face and the eyes of the parents, and there is a transformation; they are happy again.”

To reduce the risk of adverse effects like death during surgery, Onah does a surgical safety checklist before anaesthesia, the surgery, and before the patient is out of the theatre.

Since 2007, Smile Train’s local medical partners-surgeons (about 15) – have provided more than 22,000 cleft surgeries in Nigeria. But program director, West and Central Africa for the organization, Nkeiruka Obi, said the aim is to double its reach in the coming years, putting more children than ever before on track to a better future.

But Onah regularly faces a common challenge: most parents often disobey instructions to make sure those operated upon do not take solid food for 21 days, so it does not affect the repair. He says that sometimes, they give the children solid food after two weeks of operation, and when they return to the hospital after four weeks – when the speech therapist is supposed to start – it is discovered that the cleft repair is affected.

Obi says the nonprofit is working with partnering hospitals to tackle this challenge by educating parents and creating awareness on the ease of accessibility to cleft treatment and patient safety.

Meanwhile, Chinweotito’s speech is now very clear. And her mother, Egwim, said she is ready to help create awareness and help families understand that cleft is not a curse or an evil omen but an anomaly that can be corrected at no cost.

“I can clearly understand my daughter anytime she speaks now,” Egwim said. “The recovery is fast, and I am very happy she is okay.”

Chinweotito Egwim, a child born with a cleft palate in southeast Nigeria, faced numerous challenges including bullying and difficulty speaking. Her mother, Miriam Egwim, initially received incorrect information about the condition, being told it was how "God created her." Awareness about cleft conditions varies, with many Nigerian families viewing it as an evil curse.

Globally, one in 500-750 live births results in a cleft, often influenced by genetic and environmental factors. In Nigeria, about 6,186 babies are born with clefts each year. Despite prevalent myths and poverty preventing timely medical intervention, organizations like Smile Train are facilitating free surgeries.

After discovering Chinweotito's condition, Miriam was advised to wait, but eventually, they sought help from Smile Train, which arranged a successful surgery. Post-surgery, Chinweotito's speech improved significantly, and her mother is now committed to raising awareness that cleft palate is an anomaly treatable at no cost. Smile Train's initiatives in Nigeria include sponsoring surgeries, transportation, and nutrition, significantly increasing successful treatments.