In 2014, Emeka Nwachinemere was a National Youth Service Corps or NYSC member serving in Oyo State. After participating in the agro-allied component of NYSC’s Skills Acquisition and Entrepreneurship Department or SAED, he got five hectares of land to cultivate in Iseyin community.

The Agro-allied scheme seeks to spark young graduates’ interest in agriculture, and NYSC had, that year, partnered with the Oyo State government to allocate land to corps members interested in farming.

With savings from a part-time job during his university days, Nwachinemere cultivated maize expecting a great harvest. But he got a surprisingly low yield. “I was expecting at least 2.5 tons per hectare, but I got about 1.2,” the 34-year-old told Prime Progress.

The poor yield was because he lacked essential soil and seed-related knowledge: from ignorantly buying and planting uncertified seeds to spacing the farm poorly to applying insufficient fertilizer quantities.

Worse still, his harvest fell during rainy season. With no access to storage facilities, he could not dry and store his harvest for as long as he would have loved to wait for market prices to appreciate. So he sold hurriedly and cheap. Later, he discovered other farmers around him had similar problems.

Creating a solution

To solve these problems for farmers, in July 2016, the mechanical engineer founded Kitovu Technology, an agro-tech social enterprise “leveraging data that enables farmers to access profit across the agricultural value chain.”

In May 2017, Kitovu, supported by the International Fertilizer Development Centre, started a season-long pilot involving 30 farmers cultivating a hectare each.

“We mapped each farmer’s land into three bits; one portion serving as control, one worked the way the farmers usually did, and [in] the third [we] used some of the methods we had developed,” Nwachinemere said.

His team interviewed the farmers and used sensors-filled wireless electronic gadgets to collect data on the pilot farms for analysis.

“[Then] we realized that farmers are not just looking to improve their yield. For some of them, access to the market is a big issue. For others, access to finance is a big problem. For yet others, they want to ensure that they don’t lose their harvest, and they want to have options in terms of storage.”

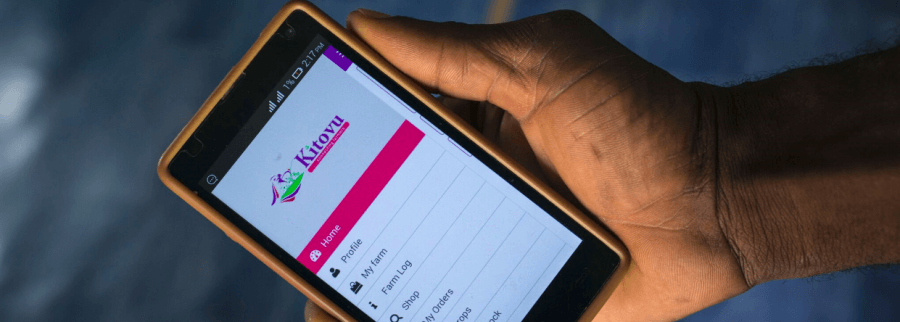

Kitovu then developed three services – Farm Park, Farm Swap, and E-procure – in one mobile application called YieldMax.

Under Farm Pack, a Kitovu-trained extension agent visits a farmer’s farm to map and “capture the GPS coordinates, what the farmer is growing, soil and satellite data, including weather and meteorological data,” Nwachinemere said.

On the YieldMax app, the agent creates an account for the farmer, inputs and saves details associated with the farmer and their farm. Kitovu analyzes these data, including “plant health analysis, water strength analysis, and weather report.”

From the result, Kitovu provides regular personalized recommendations on precise fertilizer application, crop health, weather, pesticide, and herbicide usage through the agents.

Then “we bundle [the recommedndations] with fertilizer, certified seeds and [agro]chemicals and give them to the farmers on credit,” Nwachinemere explains further. “So Farm Pack is a service that consists of subscription to those services and then the physical inputs.”

At the end of the farming cycle, the farmers pay Kitovu with their produce, swapping their produce (primarily grains) for Kitovu’s services and inputs.

“And that is what we call Farm Swap,” the founder said. “We are giving you Farm Packs on credit; you pay us at harvest with your produce.”

This way, Kitovu lessens the financial pressure smallholder farmers face during planting and improves their profit margins. Kitovu gets back its funds with profit by selling the grains it gets from farmers to large commodity buyers.

In the past, lack of access to storage facilities and big commodity buyers meant farmers hurriedly sold their produce at give-away prices, with post-harvest losses being farmers’ regular experience. To solve this, Kitovu partners with large agro-processors and commodity buyers like AFEX Commodities Exchange and Slate Farms to buy the farmers’ grains.

“We pay [the farmer] the farm yield price, and we take care of logistics, add our own markup and supply to processors. That is what we call E-procure,” Nwachinemere said.

‘touchpoints’

Since 2017, Kitovu has trained 307 agents who work with about 12,000 farmers in Oyo, Gombe, Niger, Jigawa, Kaduna, Kano, and Plateau states. One agent manages 20 to 50 farmers and attends farmers’ engagements meetings to introduce Kitovu and onboard farmers.

“There are just eight of us in the [core] team, so they [agents] are our touchpoints with the farmers. And this serves as a form of employment for the agents,” Nwachinemere said.

Adegbola Olusola has been a farmer for about 10 years. In 2019, after a Kitovu agent onboarded him, “I benefited from fertilizer recommendations and plant health analysis,” he said. “My yield increased from 10-12 bags of maize per hectare to nearly double of that.”

Nwachinemere said agents manage farmers’ details on the app to eliminate the limitation of lack of access to a smartphone or lack of knowledge to operate one. But farmers who have and can operate smartphones can download and manage their details on the app.

“Storage X”

Last February, Kitovu took a step further and partnered with the Niger and Gombe state governments to introduce “Storage X”, an electronic warehousing system allowing farmers to store their grains for up to six months and sell them when prices are favourable. It started with one pilot warehouse in Niger and then scaled to six in the two states (three in each).

“They (governments) gave us warehouses at subsidized rates. We equipped them with hermetic storage, driers, weighing scales, and others,” Nwachinemere said, adding that nearly 2000 smallholder farmers are now using the warehouses at a fee. A farmer could decide to pay the fee immediately or when they sell their stored produce.

Plus, a farmer can use their stored produce as collateral to collect a loan from Kitovu – up to 50% of the total value of their stored grains – and pay with interest upon sale of the preserved goods.

Kitovu also does “commodity aggregation” for large commodities buyers at a fee to raise funds for its operations. “If a big buyer, like AFEX, tells us ‘we need 1000 tons of maize,’ we can afford to get [it] for them from different farmers across different locations as long as they give us the specifications,” Nwachinemere explained commodity aggregation.

Yet, not all Storage X farmers who desire a loan get it because Kitovu’s revenue inflow is insufficient to meet all loan requests and other administrative expenses. For the same reason, Kitovu has limited itself to grain-storing warehouses despite continued requests to expand to other farm produce like tubers and vegetables to accommodate more farmers in the two states or expand Farm Pack to more states.

He said the social enterprise has been trying to get commercial banks to handle the loan aspect of Storage X but has been largely unsuccessful because some banks say Kitovu must provide up to 40% of the loan to farmers. Others are demanding interest rates Kitovu feels are unfair to farmers.

“If we are doing 5000 farmers, it would require about N500 million to fund them because, on average, they would get N100,000 each as a loan. Telling us to bring 40% means they expect us to bring roughly N200 million. If we had the N200million, we would go ahead and start giving to the farmers,” Nwachinemere said.

He is now considering a possible partnership with private financial initiatives while calling for government policies that would make it easier for commercial banks to lend money to smallholder farmers at low-interest rates.

Hunger in Nigeria

About 811 million or 9.9% of the global population go to bed hungry every day due to poverty, climate change and conflicts that affect food production and distribution. The number of undernourished people has grown by 161 million since 2019, with COVID-19 and its associated 2020-2021 economic disruptions contributing largely.

In Nigeria, since 2018, 21.4% of the 213 million population has experienced hunger due to factors similar to those affecting global food systems. As of April 2022, 39% of the population lives in extreme poverty. Desertification in northern Nigeria and other climatic factors across the country gravely affect agriculture, not to mention frequent herder-farmers clashes, Boko Haram activities, banditry, and farmers’ lack of access to information and resources.

Last year, the Global Hunger Index said, “Nigeria has a level of hunger that is serious,” ranking the country 103 out of 116 countries facing food insecurity.

Nwachinemere said this food insecurity is what he is fighting with his social enterprise, and the result thus far aligns with what he had in mind when he named it “Kitovu”, a Swahili word that means navel.

“My thinking when I was starting Kitovu was to build a system that is to the agricultural sector what the umbilical cord is to a child in the mother’s belly. We want to be that system that connects small scale farmers with everything they need to get the best results,” he said.