MAKURDI, BENUE – Mimidoo Akombo’s parents were poor, so they could not afford to train her beyond primary education. But when she got married later and gave birth to her son, Sunday, in 2013, she and her husband – whose highest level of education was secondary school – vowed to do their best to support the boy’s education up to university.

However, a tragic event soon happened and shattered the whole plan. About 11 pm one Saturday in November 2018, AK-47-wielding herders invaded Mbagwa, their community in Makurdi local government, Benue State, dragging residents out of their homes, looting, and shooting whoever tried to resist them.

“My husband was killed that night because he wanted to carry a few things that could sustain us,” 32-year-old Akombo recalls, grieving.

Since 2015, clashes between herders – mainly of Nigeria’s Fulani tribe – and farming communities have escalated over grazing rights, resulting in thousands of deaths, especially in the north-central states of Benue, Plateau, Nassarawa and Taraba, where the herdsmen often attack unprepared communities at odd hours.

For example, in the first half of 2018 alone, 1,300 deaths associated with herders-farmers clashes were recorded across the country; that was six times higher than those caused by the jihadist group Boko Haram within the same period. Meanwhile, the Global Terrorism Index in 2015 named violent Nigerian Fulani herders as the world’s fourth most deadly terror group.

Such attacks have resulted in massive displacements. In Benue, authorities estimate that a third of the state’s nearly six million people have been displaced from their communities, living in over 20 internally displaced persons (IDP) camps and host communities.

Akombo and her son escaped that night to the Tse-Yandev IDP camp in Makurdi, one of several managed by the state government. But as expected, camp life is nowhere near comfortable. Besides IDPs’ regular complaint that the government hardly gives them enough basic things like food and clean water, living in the Tse-Yandev camp – or any other – also means children, who make up over 50% of the displaced, have no access to schools.

The Benue State government says 80% of children in IDP camps were at various levels of schooling in their communities before their displacement. The other 20% were either below school age or from low-income families that could not afford their education.

Filling the gap

Amos Terhumba Agber is a sociologist living several kilometers away from Tse-Yandev IDP camp. One day in November 2021, he entered the camp for the first time just to observe what life was like inside it. And what he saw was “really disturbing” – unkempt, hungry-looking children loitered during school hours.

When he asked their parents why the kids were not attending school, most told him they could not afford the cost, and others said they had more pressing issues to worry about than school.

“And it struck my heart,” Agber said.

From then on, Agber started thinking of ways he could help. First, he thought about crowdfunding to enrol the kids in public schools close to the camp. Then he learned that he would need over N7.5 million (about $15,000 at the time) to register over 500 kids in camp (N15,000 or $30 for each).

Plus, he would need even more money to provide them with other school materials and pay each child’s tuition fee three terms a year. That was too heavy an amount to raise within a short period, given the kids’ situation urgency.

So he came up with a second option: use a dilapidated building inside the camp as a makeshift school run by volunteers and able to accommodate up to 300 children of primary school age. That was how 28-year-old Agber started the Fortress of the Vulnerable Child Rescue Initiative in late November 2021 after talking to five friends who agreed to work with him.

They raised funds through their network of friends and acquaintances and divided the 300 kids into four clusters (classes) – 70 kids per cluster on average.

“We had to talk to all the children by literacy level. We discovered some of them could identify the alphabets, some couldn’t, and some could identify even two letter words,” Agber said. “[So]…we [put] those [who] couldn’t identify the English Alphabet in one class, another [class] for [those] who could identify them but didn’t know how to write. We also had a class [for] literacy, reading, and comprehension.”

Nigeria’s primary education system runs a primary 1-6 system. But the initiative had to run a cluster system because “If we [did] primary 1 to 6, we will not get enough people [workforce] for each class. We had a team of eight [volunteer teachers], so we separated the classes [to] have at least two [teachers] per class,” he said.

The teachers handle basic subjects like civic education, mathematics, English, comprehension, and agriculture. “We have contact with these children thrice a week and two hours (each time). Each [teacher] has at least two classes to attend,” Agber explained.

While the teaching the initiative provides might not be up to the government’s approved standard and parents’ desire for their children, it does give the kids the primary education they need, at least for as long as they are in camp.

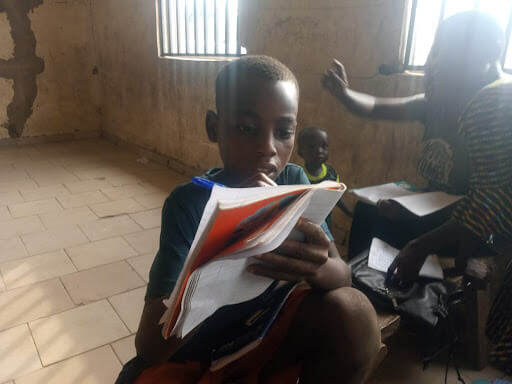

For Akombo, who did not hesitate to enrol Sunday once the initiative started, it revived her dream of seeing her son learn how to read and write in class.

“Nobody ever imagines a school talk more of a passionate one run by NGOs and not the government,” she said. “[I] cannot describe what I feel [every time I see] my son read and write [or] I see him with books either studying or doing his homework.”

Meanwhile, Agber’s initiative also gives each pupil a meal every school day through the support of the International Christian Concern or ICC. ICC also helps pay each volunteer N5000 stipend weekly.

But the initiative does not cover children of secondary school age for a lack of resources and space, meaning most of those in this category are still without access to education.

And the initiative’s sustenance is threatened. Three months ago, one side of the makeshift school’s dilapidated structure collapsed. Fortunately, nobody was hurt. But camp authorities had to pull down the entire structure to avoid a later potential total collapse that could lead to fatalities. Currently, the kids meet under tree shades in the camp to learn.

Unfortunately, the initiative could not access more funding for more than a year to either rent or build a structure for learning because it was not legally registered, and donor organisations like dealing with formally registered groups.

Agber said he could not register the initiative initially because “When we asked how much [it would take], it was N150,000. If I had that N150k, I would prefer to put it in the school than do the legality,” he said.

Besides, the N5000 stipend to volunteers is below what some volunteers expect. So “our volunteers keep decreasing; we only have six now [from a high of 10 in early 2022].”

But with the support of friends, last March, Agber began the long and expensive process of registering the initiative as a nonprofit with the Corporate Affairs Commission and completed it two months after. He is now using the registration documents to open a bank account in the initiative’s name to which potential donors can feel confident enough to donate.

With more funding, he plans to build the school into a full-fledged one for vulnerable children beyond IDPs. But despite the not-too-good current learning atmosphere, Akombo is happy with Sunday’s progress.

“I can see him reading [and hopefully] our lives will soon change for the better,” she said, implying that when she returns to her community when it becomes safe to do so, she will work to support Sunday’s education beyond the primary level.

This story was produced with the support of Nigeria Health Watch through the Solutions Journalism Network, a nonprofit organisation dedicated to rigorous and compelling reporting about responses to social problems.

MAKURDI, BENUE — Mimidoo Akombo's educational aspirations for her son, Sunday, were devastated when AK-47-wielding herders attacked their community in 2018, killing her husband. This tragedy is part of the larger conflict between herders and farmers in Nigeria, especially in north-central states, resulting in thousands of deaths and displacements.

Akombo and her son ended up in the Tse-Yandev IDP camp in Makurdi, where children, who form over 50% of the displaced population, lack access to education due to resources and facilities constraints. Recognizing this gap, sociologist Amos Terhumba Agber started the Fortress of the Vulnerable Child Rescue Initiative in late November 2021 to provide basic education using a dilapidated building in the camp.

The initiative, run by volunteers and funded through personal networks, serves around 300 children of primary school age, with separate classes based on literacy levels. It covers basic subjects and even provides meals through support from the International Christian Concern. The initiative, while not meeting government standards fully, ensures children like Sunday receive some form of education. However, it faces challenges such as lack of legal registration, funding, and dwindling volunteer numbers.

Despite these setbacks, Agber successfully registered the initiative as a nonprofit with the Corporate Affairs Commission, opening doors for potential funding. With more resources, he aims to expand the initiative to a full-fledged school for vulnerable children. Akombo remains hopeful that Sunday’s education will continue and improve their future prospects.