Kayode Akinwumi was returning home from primary school one sultry November afternoon when his heart muscles suddenly went into a spasm. His breathing became laboured, his vision blurred and he teetered helplessly to the ground, gasping for air. Rushing to his rescue, bystanders hauled him home, where he was immediately administered an intravenous drip that later stabilised his health.

Akinwumi’s mother recognised her son’s symptoms as strikingly similar to those suffered by her husband. Geneticists maintain that asthma runs in the genes, and children born to asthmatic parents face a high chance of developing the disease too. This genetic predisposition was now manifest in the eight-year-old.

In the years that followed, Akinwumi treaded with more caution—abstaining from cold water, avoiding fried foods and staying away from smoke and other irritants that could trigger another asthma attack. “During the harmattan last year, I had to endure short breaths for days because I didn’t have an inhaler. Only one store had an inhaler in my neighbourhood, and it was almost impossible to walk down there,” Kayode said.

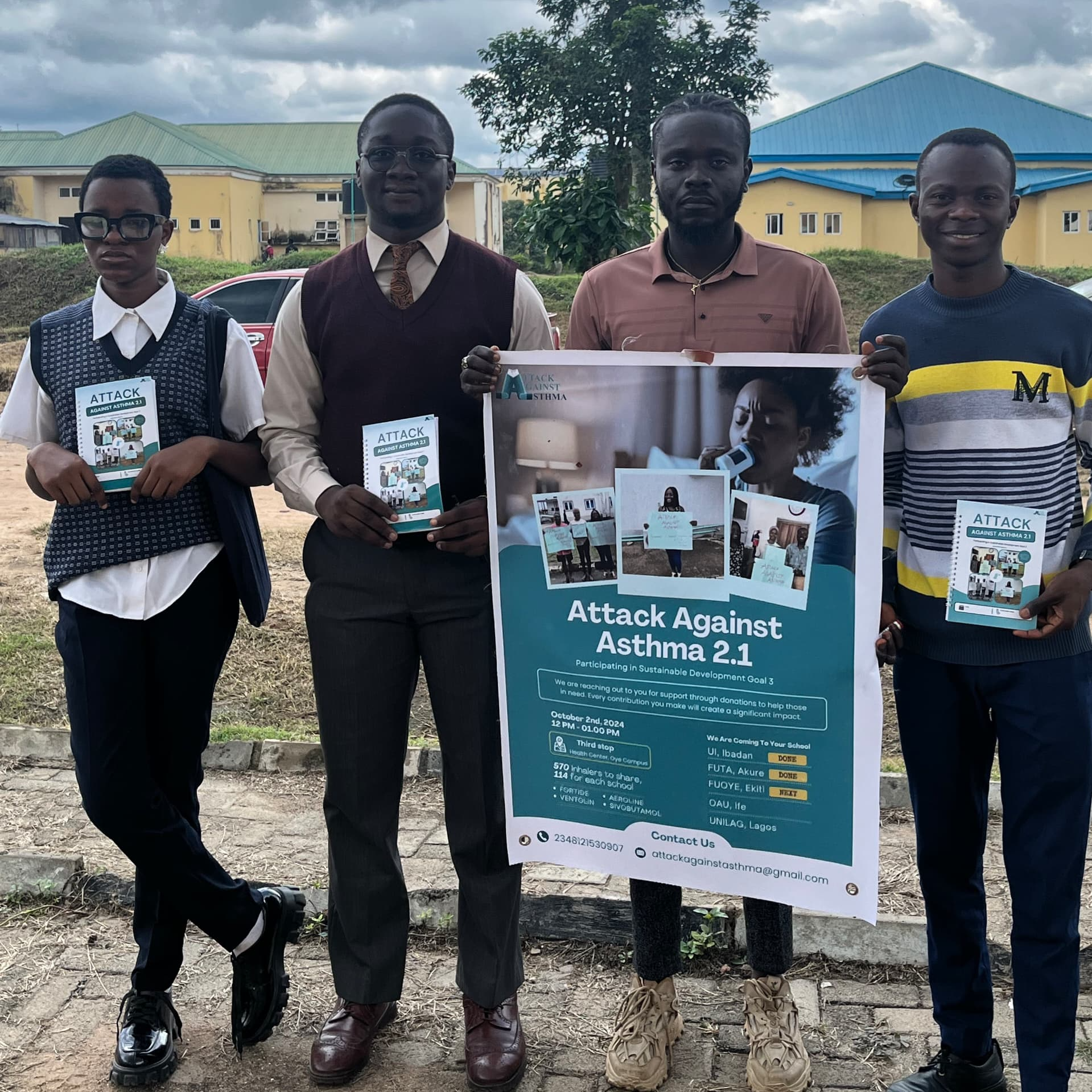

In a similar vein, Temitope Omosebi, a graduate student of psychology, recalled the haunting memories of seeing his aunt struggle for breath during recurring asthma episodes, which left a deep impression in him and led him to launch an initiative called Attack Against Asthma in September 2023.

Similar struggles resonate with many in Nigeria, where an estimated 13 million people suffer from asthma, with a significant percentage facing life-threatening risks as spiralling inflation in the country takes a huge toll on the cost of inhalers. The exit of international pharmaceutical companies from Nigeria in recent months has compounded the woes, resulting in a critical shortage of medications on the market.

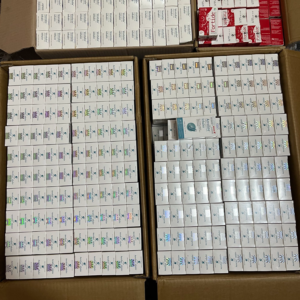

In August 2023, Nigeria’s subsidiary of the British pharmaceutical firm GlaxoSmithKline (GSK) announced that it was shutting down operations in the face of the country’s deteriorating economic policies. GSK had been a leading manufacturer of asthma inhalers for more than five decades.

Amid this grim background, Omosebi began doling out cash to university students to help them cushion the cost of inhalers, “but I observed that this might not actually achieve the intended objective,” he explained, highlighting the heavy financial strain that resulted.

So he turned to crowdfunding, rallying public support and raising roughly N4.5 million (together with personal funds) used to purchase Aeroline, Ventolin and Fortide inhalers for university students battling asthma.

In the year since its launch, the campaign has disbursed over 700 inhalers in Nigeria’s southwest region, including Lagos and Ibadan. “Currently we’re focusing on schools in the South West because of their proximity, and going to them does not require a large amount of financial obligation,” he said, citing travel costs and security concerns as barriers to expanding nationwide.

Still it hasn’t been smooth sailing for the Attack Against Asthma campaign. “You’d have to meet the dean of students’ affairs, the health centre administrator and other relevant stakeholders,” Omosebi said, bemoaning the bureaucratic hurdles in gaining institutional approval to share inhalers in campuses. “Sometimes you have to always keep checking up on them to get feedback,” he added.

Despite the odds, the initiative has recorded remarkable success, even outside tertiary institutions. At the University of Ibadan, a mother who could not afford the N20,000 Fortide inhaler brought her asthmatic daughter to the awareness campaigns, where free inhalers were given out. “The expression on the mother’s face was priceless,” recalled Omosebi, who has extended the support to non-students who can provide proof of need.

Health outreaches like this can be prone to misuse, putting the inhalers out of reach to those who need them. To ensure that the inhalers are distributed fairly, Omosebi supplies part of the medications to healthcare centres within the universities while requiring students to present a doctor’s prescription or show up with their used inhalers at his awareness campaigns.

At the University of Ibadan, for example, students in need of inhalers are screened through several tests to ascertain their asthmatic conditions. “All I did was go [to the asthma clinic] with my ID card and speak to the nurse who was attached to the clinic. I asked about my health before receiving a can of Aeroline inhaler,” explained a student beneficiary of the Attack Against Asthma campaign who asked not to be named.

Got mine today !

Thank youuuuuuu #AttackAgainstAsthma https://t.co/LmnzX4M42h pic.twitter.com/wHdWvBaKF1— amaris 🤍💙 (@thelittleamaris) September 25, 2024

Similar rigorous vetting processes have been created in several other campuses where the campaign has been launched. Medical personnel review students’ medical records during registration or screen new cases.

Omosebi’s initiative against asthma has similarly met with a wide reception from university authorities. Egai Wariebimowei Ebimiebo, a medical officer at the Federal University in Oye-Ekiti, reported a significant drop in the number of asthma-related emergencies at the school’s health centre. “Previously, we had to manage life-threatening asthma about two times in a week, while an average of two complaints of acute or recurrent asthma cases were filed on a daily basis,” recounted Ebimeibo. “We’ve not had to nebulise students as often as we did before,” he said, referring to a method of treating breathing difficulties through a medicated fine spray.

Omosebi’s campaign against asthma comes in the wake of a surge of low-grade inhalers on the market since GSK’s exit. “The less expensive inhalers that these students can afford are mostly adulterated,” continued Ebimiebo. “Two puffs of inhaler would normally give patients respite, but that is no longer the case.” Earlier in March, a student of Ebimiebo’s university died after his inhalers reportedly failed to nurse him back to stable health.

Beyond sharing free inhalers, the Attack Against Asthma initiative has been pivotal in fostering public knowledge about the disease and debunking long-held stereotypes. “We’ve had to deal with cases where students believe that asthma is the work of the devil and generally disregard it, avoiding treatment,” said the chief nursing officer at the University of Ibadan Health Centre. “Others do not believe that asthma can be controlled.”

Social media has been instrumental in spreading the message. “I came across his post on X where he shared that the organisation would be coming to the University of Ibadan, and so I waited, anticipating his arrival,” said Kayode Akinwumi, now a university student in his twenties. Unlike before, he now had two inhalers to navigate the harmattan dust.

To broaden the campaign’s reach to other tertiary institutions and vulnerable populations across Nigeria, Omosebi envisions setting up branches in each of the country’s geopolitical zones. Part of this strategy, he explained, would involve leveraging technology to improve access to asthma healthcare. “We are looking at creating an app where students can apply for inhalers at registered pharmacies, and we’ll pay on their behalf,” he said.

The initiative also aims to distribute 2000 inhalers in 2025 to “reduce asthma mortality rates,” he said.

For Omosebi, the war against asthma is more than just a mission in reducing the burden for asthma sufferers in Nigeria. It is a source of personal fulfilment. “I love solving practical problems such as improving asthma care in Nigeria. It meets my principles and makes me feel fulfilled,” he noted.

This story was produced with the support of Nigeria Health Watch through the Solutions Journalism Network, a nonprofit organisation dedicated to rigorous and compelling reporting about responses to social problems.

Kayode Akinwumi experienced a severe asthma attack, highlighting his genetic predisposition to the condition inherited from his father. To manage his asthma, Akinwumi adopted lifestyle changes but faced difficulties due to limited access to inhalers caused by economic challenges and the withdrawal of major pharmaceutical brands like GlaxoSmithKline from Nigeria, which has led to a depletion of asthma medications. In response to the urgent need for affordable asthma care, Temitope Omosebi launched the "Attack Against Asthma" initiative to distribute inhalers and raise awareness about asthma management.

Omosebi’s campaign, which began in September 2023, has provided approximately 600 inhalers to students in southwestern Nigeria and aims to tackle the shortage of quality asthma medications. The initiative also educates the public on asthma triggers to debunk myths about the disease. Despite bureaucratic challenges in distributing inhalers on campuses, Omosebi has found success by using public crowdfunding and personal contributions, and aims to expand his reach with ambitions to establish technological solutions like an app that allows students to apply for inhalers at registered pharmacies.

The campaign has led to a decline in asthma-related emergencies reported by health officers at universities. Omosebi plans to distribute 2,000 inhalers in 2025, aiming to reduce asthma mortality rates across Nigeria. His efforts serve as both a personal fulfillment and a commitment to improving asthma care, showing the potential for a significant reduction in asthma struggles with combined community effort and innovative solutions.