When an unflattering photo of Nollywood actress Nkechi Blessing surfaced on social media, it triggered a cascade of jeers. The viral photo, captured at gym, showed her flabby midsection in an unguarded pose. Still the uproar also reinforced the age-old prejudice against fat people in Nigeria.

Among the Efiks, in Cross River, the fattening room was a celebrated tradition associated with good health and fertility. As a rite of passage between adolescence and womanhood, maidens were secluded for weeks on end and fed on a variety of meals.

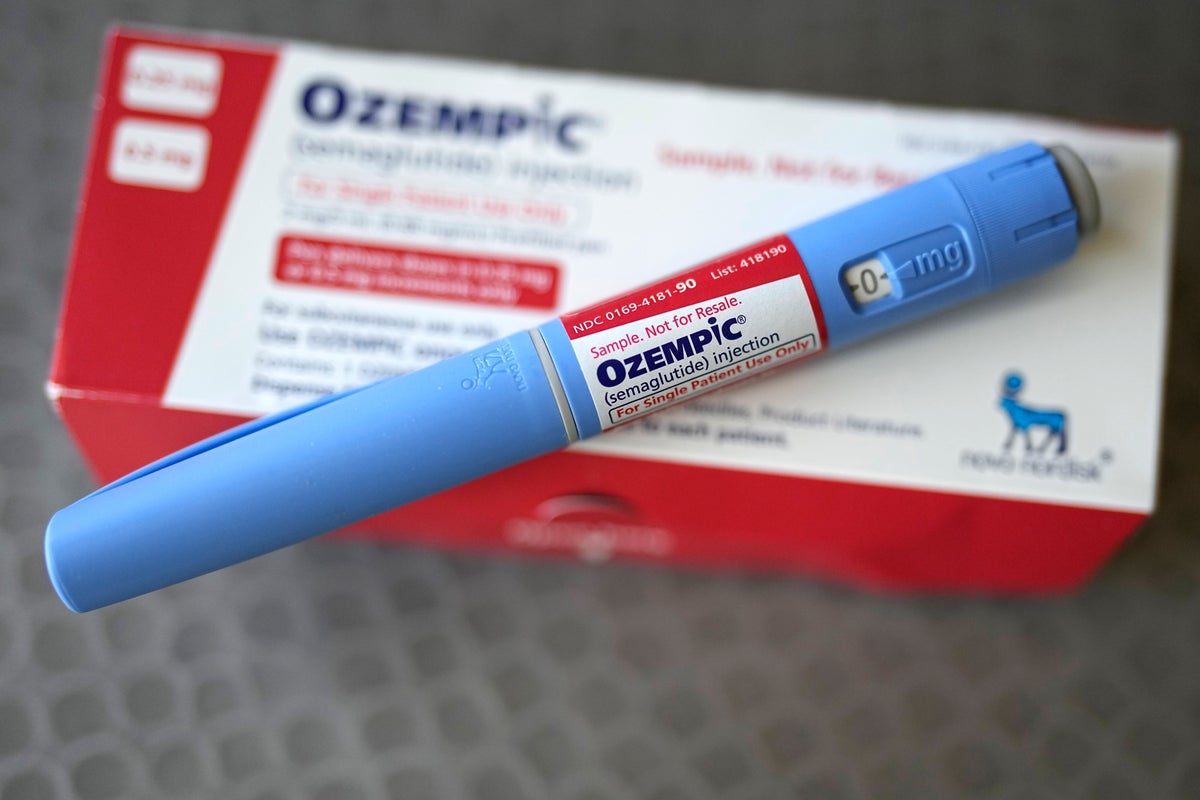

Not too long ago, body positivity—that is, accepting and appreciating one’s body size—seemed to be gaining traction worldwide, but ideals have shifted, especially with the discovery of weight-loss drugs like Ozempic.

The departure from this traditional view towards the ultra-slim figure—or what’s typically known as the ballet body—shows how the body has become a tradable asset across the world, modified for social validation and economic gain.

Indeed, a medley of factors—including the fashion industry and the celebrity culture—has propelled an interest in thinness as a beauty ideal.

Celebrities such as Elon Musk and Oprah Winfrey have spoken openly about taking semaglutide (the active ingredient in drugs like Ozempic) for weight loss, accelerating demand for the drug. Novo Nordisk, which manufactures Ozempic, is reported to be the most valuable company in Europe.

A similar dynamic is also at play in Nigeria. Celebrities, previously noted for their plump figures, have emerged almost overnight with slimmer physiques. Crediting shifts in lifestyle, rather than surgery, for their rapid body transformation, these celebrities leave fans pining for a similar shape.

The economics of thinness

The pursuit of thinness has spurred a growing market for unregulated products—slimming teas, pills and herbal tinctures—promoted by social-media influencers.

In early 2024, NAFDAC raised alarm about fake Ozempic packs that had flooded the country following increased demand.

Cosmetic surgery is also booming in the country as health clinics open in major cities like Lagos and Abuja, catering to a growing number of young Nigerian women seeking the slim-thick ideal, including Brazilian butt lifts and tummy tucks.

To cater to the rising obsession around thinness, many ill-trained personnel are offering cosmetic procedures at a fraction of the cost. This has inevitably led to a cottage industry of unlicensed practitioners where profit trumps safety.

Yet the widespread body dissatisfaction is not only a cosmetic concern. An array of mental-health issues contribute to the mix, with disturbing psychological fallouts.

According to one study, over 68% of urban Nigerian women aged 18 to 35 lamented body dissatisfaction, citing social media as the primary culprit. As the ridicule surrounding Nkechi Blessing’s picture shows, body image shame is acute on Nigerian social media.

The psychic response to this discrimination is deeper levels of depression and low self-esteem.

As if to redeem her image, Blessing clapped back at her detractors, hurling curses at the anonymous person who took her shot in the gym. In a recent post on X, she shared a close-up of herself holding the latest IPhone 17, alongside another picture of her gadgets and perfumes. Many users interpreted the post as a childish riposte at her detractors.

As social-media influencers have begun to cash in on the booming enthusiasm for thinness, trends like prolonged fasting and reduced calorie intake have taken root. Posts promoting the virtues of skipping breakfast are commonplace on social media—which has left unwholesome results.

A 2021 study on female undergraduates found a worrisome prevalence of disordered eating, with 17.1% of the sample classified as being high risk. In a similar vein, another study among dermatology patients found a 36% prevalence rate of Body Dysmorphic Disorder (BDD), a mental-health condition marked by an obsessive preoccupation with perceived physical flaws.

The pursuit of thinness in contemporary society is not a simple aesthetic trend. The journey towards a narrower waist line or trim figure is fraught with health risks.

As such, tackling the crisis requires a multi-pronged and coordinated approach. There’s an urgent need for stricter regulations and enforcement to dismantle the black markets for dangerous products and quack doctors.

The Nigerian government’s regulatory framework for weight-loss supplements is weak.

Nigeria is one of the few countries with a minimum legal age for purchasing WLS, but these regulatory gaps allow a global dietary supplement industry—valued at over $300 billion—to sell products that are not only ineffective but potentially fatal.

Beyond regulation, there is an urgent need for widespread public education. These campaigns will challenge the stigma surrounding mental health issues like eating disorders and BDD.

Nevertheless, a collective effort is needed to redefine beauty to help Nigeria heal from this profound pursuit.

Summary not available at this time.