Every year, approximately 351,000 hectares of land in Nigeria are wiped out by expanding deserts and land degradation. In Yobe State, the ecological assault is more acute: between 25,000 and 30,000 hectares are lost annually to advancing sand and degraded soils.

Landsat imagery shows tree cover in Yobe collapsed from around 582.8 km² in 1975 to just 284.7 km² by 2013. Shrubs and grasslands also dwindled from nearly 1,990 km² to just 669 km² within the same period.

What does this mean for communities?

Encroaching desertification means that farmers are increasingly running out of available space for cultivation.

This, in turn, results in less income as harvests take a hit and output falls short of national demand. With fewer options for income and meals, many households face hunger and deeper poverty.

This August, Yobe State launched a bold new tree-planting initiative named after the state governor, Mai Mala Buni.

Buni’s Initiative for Desert Reclamation and Restoration of Degraded Lands features a statewide competition among emirates, schools, and residential areas, offering attractive rewards to stir community involvement.

The programme draws on former initiatives like the gum Arabic plantations across the state’s three senatorial districts, roadside planting, shelter belts in estates and schools, and the installation of six weather-monitoring stations.

The state has partnered with the World Bank, the African Development Bank, and the Great Green Wall initiative to bolster capacity and funding.

A state committee, chaired by Idi Barde Gubana, the state’s deputy governor, will orchestrate activities, site identification, land preparation, seedling distribution, and technical support. Government nurseries in Damaturu, Potiskum, and Garin-Alkali are stocked with seedlings, ready for community uptake this rainy season.

How trees tackle desertification

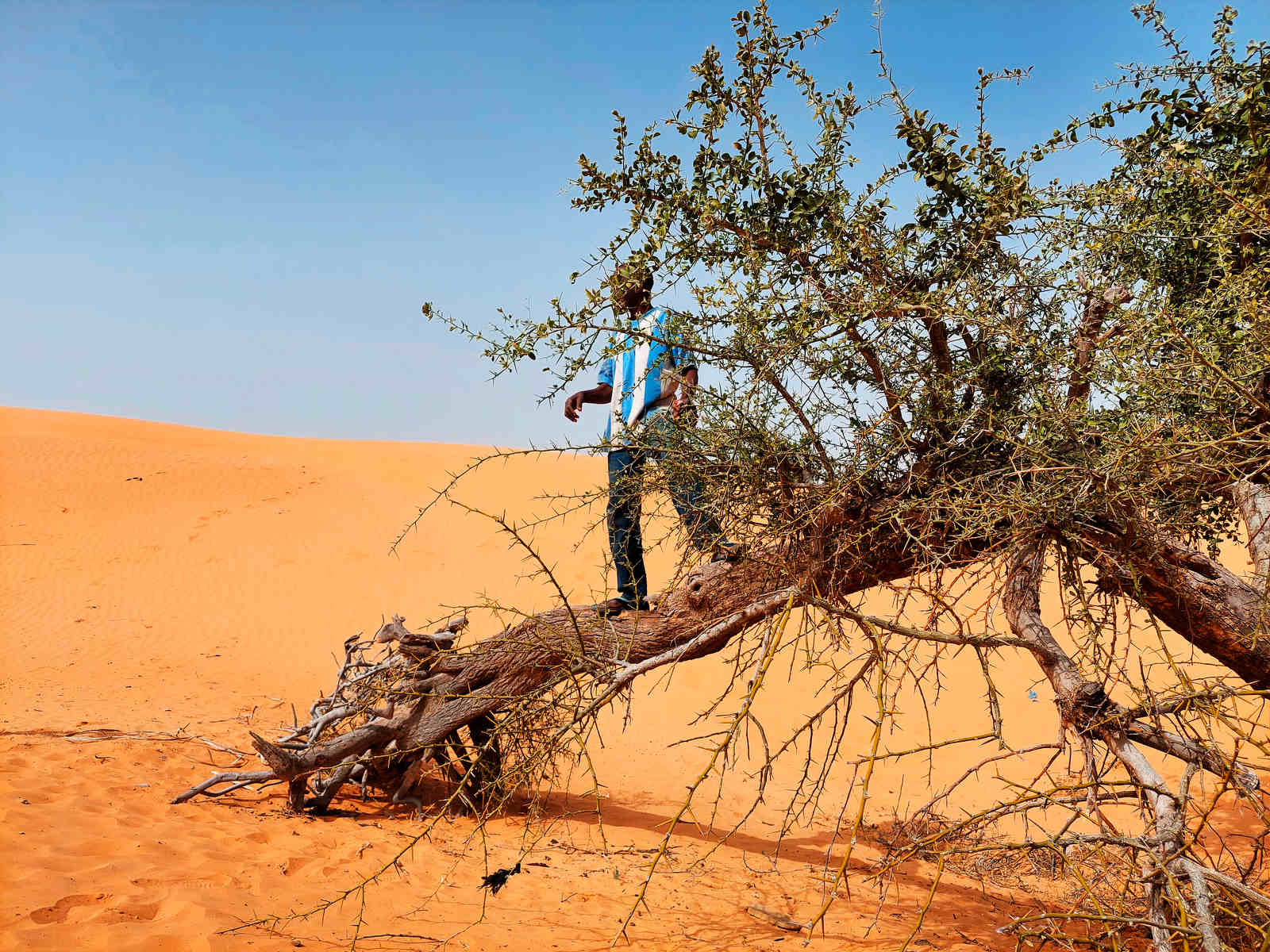

With well-established roots, trees help to stabilise the soil and arrest wind erosion. Leaves and branches, meanwhile, shield the soil from the sun’s rays, reducing evaporation and locking in moisture.

By holding the soil firmly and blocking strong winds, trees stop sand dunes from spreading. Their shade and branches create space for life, attracting birds, insects, and smaller plants. When leaves fall and rot, they enrich the soil, help it hold water, and make it healthier. Over time, this allows grasses and shrubs to grow back and cover the land again.

Trees also make the weather around them gentler. Through evapotranspiration—a process in which plants release water into the air—they add moisture and slightly cool the surroundings. These changes are very important for healing dry and damaged lands.

Sustaining the gains

A tree-planting campaign in Yobe is only half the battle. Young trees need watering, protection from grazing animals, and community stewardship. Shelter belts—lines of trees planted around compounds and schools—help to protect soil and create micro-visual barriers between sand and farmland.

Monitoring is key. With six weather stations installed across Yobe, government agencies can track rainfall patterns and heat trends, adjusting planting strategies accordingly. Seedling supply from state nurseries ensures ongoing access.

Creating a sense of competition among fosters a sense of ownership among the communities and schools, ensuring that saplings survive past planting season.

What Worked—and what didn’t

History provides plenty of insights. In August 2021, Yobe and the UN distributed 3 million tree seedlings to fight desertification. Although it was an impressive scale, long-term survival rates were unclear.

In June 2024, a localized campaign in Fika planted around 200 trees to mark World Environment Day. While modest, it raised environmental awareness and mobilized the community.

However, a 2022 investigation into the Great Green Wall efforts revealed issues with inefficiencies and weak community buy-in; dead saplings and funding shortfalls undermined progress.

Desertification is not an abstract threat; it is concrete, mapped, and encroaching upon farms, homes, and water sources.

The loss of forest, grass, and soil directly undermines rural livelihoods in Yobe. But trees offer a tangible remedy: soil protection, moisture retention, cooler microclimates, and biodiversity revival.

If seedlings survive, communities care, and monitoring continues, this year’s campaign could mark a turning point. The real test lies not in how many trees are planted but in how many reach maturity.