As the golden sun dipped below the horizon, casting its vibrant hues upon the serene landscape of Nagi village, Awashima returned from the village stream, a woven basket balanced gracefully upon her head.

While the evening air carried a sense of tranquillity, an impending storm, the shadows of tradition, lurked in the darkness, patiently waiting to seize her fate and shatter her world.

On this fateful evening, beneath the canopy of ancient trees, Awashima’s steps faltered, her heart quickening with trepidation. Her path crossed with her suitor’s in a cruel twist of tradition. In an instant, she was whisked away from the familiar, plunging into a nightmarish journey of abduction dictated by the ancient practice that haunted their village.

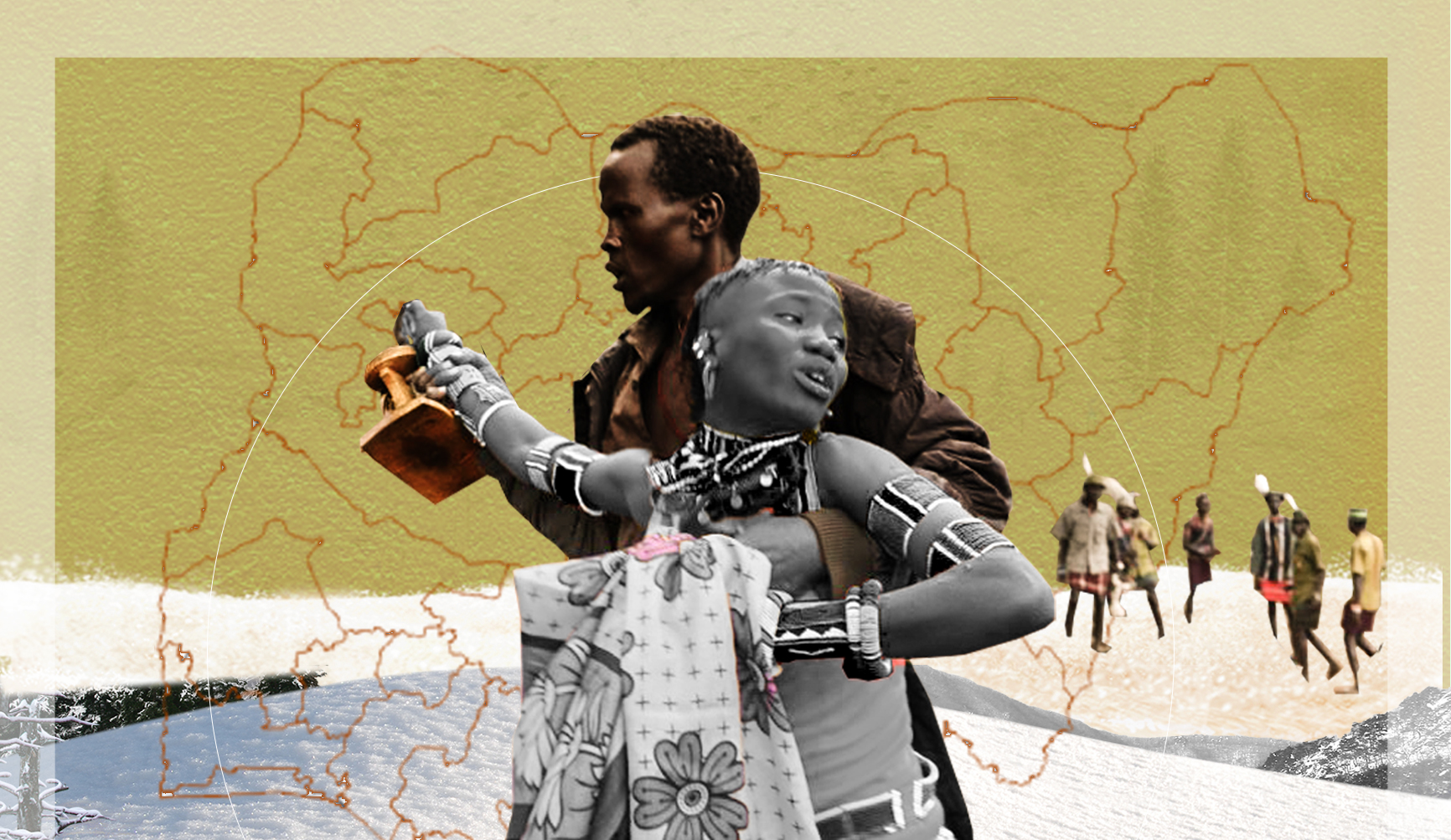

In the depths of Nagi village, Gwer West of Benue State, a repressive cultural practice known as “bride abduction” has persisted for generations. Awashima’s story depicts many young women who have fallen victim to this archaic tradition.

Notwithstanding its different names and regional variations, the underlying dynamics remain the same: a woman is taken against her will and forced into a marital relationship.

Bride abduction is believed to have ancient origins, rooted in notions of power, control, and ownership. It emerged in societies where women were considered commodities, and marriage was seen as a transaction between families rather than a union based on mutual consent.

Over time, this practice became deeply ingrained in certain cultures and continues to persist today, albeit in diminishing numbers, an example being Rukuba, a district in Jos North Local Government Area in Nigeria’s north-central Plateau State.

In a world that should celebrate love, the brutal act of kidnapping a woman, sometimes against her will, is how you ask for her hand in marriage or prove to the family and the community that you are a capable young man.

More often than not, if the bride’s mother has taken a liking to a particular suitor, as against the other suitors coming, she could arrange with the suitor and his friends to abduct the bride.

Other times it could be a mutual agreement between the bride and suitor or solely within the capacity of the suitor. In Awashima’s case, a regular market day quickly became a road less travelled through tradition.

While some may argue for cultural relativism, claiming that each society has its values and practices, examining the human rights implications of bride abduction is essential.

The Universal Declaration of Human Rights unequivocally asserts that “every individual is entitled to freedom, dignity, and the right to choose their own destiny.” This cultural practice flagrantly violates these fundamental rights by subjecting women to abduction.

Advocates of bride abduction often justify the practice by citing cultural norms and traditions. They argue that it ensures social cohesion, maintains family honour, and prevents women from engaging in relationships deemed inappropriate by the community. However, such justifications ignore the fundamental principles of human rights, individual freedom, and consent.

Bride abduction is a stark reminder of the deep-seated gender inequalities in societies like Nagi village. The practice reduces women to mere objects, denying them their autonomy and relegating them to the status of property to be claimed.

It perpetuates a patriarchal power structure, reinforcing that women are subordinate to men and their desires. Such oppressive practices hinder the progress towards gender equality, preventing women from realising their full potential in all spheres of life.

The long-lasting psychological effects of bride abduction cannot be overlooked. Awashima’s harrowing experience is not an isolated incident; countless women endure emotional trauma, anxiety, depression, and post-traumatic stress disorder due to being forcibly separated from their families and communities. The psychological scars are often overlooked, perpetuating a cycle of suffering for future generations.

Addressing the issue of bride abduction necessitates proactive measures from both the government and human rights organisations. Legislative reforms must be enacted to criminalise this archaic practice and protect women’s rights.

Simultaneously, awareness campaigns, sensitisation programs, and support services must be implemented to empower victims and educate communities about the harmful consequences of bride abduction.

Awashima eventually fell sick and died after 23 years of a forced marriage that produced six children. And it was until the last years of her life that her abductor husband fulfilled his traditionally required obligation of paying her bride price as a public testimony of their marriage.

Even more painful was that one of her daughters also became a victim of bride abduction – leaving her with a till-death sadness.

“Six children and 23 years were what it took to finally fulfil the obligation of paying the bride price,” Awashima told her brother before death. “I see the pain when one of my daughters (17) went through the same thing.”

Awashima’s story is a sobering reminder of the deep-rooted repressive cultural practices that persist in many corners of the world. Shedding light on the bride abduction phenomenon exposes the inherent violations of human rights and the perpetuation of gender inequalities.

Societies like Nagi village and Rukuba district must confront these issues head-on, fostering a future where individual autonomy, freedom, and dignity are revered above all else.

Only through education, legislation, and grassroots activism can we hope to dismantle these oppressive structures and pave the way for a more just and equitable society.

As the sun sets on Nagi village, Awashima returns from the stream, unaware that an ancient practice known as "bride abduction" is about to shatter her peace. This tradition, deeply ingrained in the culture of Gwer West in Benue State and other regions, involves forcibly taking a woman against her will into marriage.

Awashima's story is a grim reflection of countless women subjected to this practice, which is rooted in notions of power, control, and viewing women as commodities. In some regions like Jos North in Nigeria's Plateau State, the practice persists, though in diminishing numbers.

This cultural norm often involves the family's and sometimes the bride's complicity, illustrating the complex social dynamics at play. However, it starkly violates fundamental human rights, such as freedom and the right to consent to marriage, enshrined in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights.

Advocates of the practice argue it upholds social cohesion and family honor but ignore the severe human rights violations and the perpetuation of gender inequality. The psychological toll on women like Awashima is significant, causing emotional trauma and long-term mental health issues.

Awashima's life, marred by forced marriage and personal grief seeing her daughter endure the same fate, underscores the urgent need for action. Addressing bride abduction requires legislative reforms, awareness campaigns, and support services to protect women's rights and dismantle these repressive cultural practices.

Her story is a stark reminder that societies must confront and eradicate such traditions to promote individual autonomy, freedom, and dignity, moving towards a more just and equitable world.