EKUREKU, CROSS RIVER: On December 14, 2022, Eleng Orji Imoke’s life was torn apart after his wife became seriously ill. She had started complaining of weakness in her joints and then a stomach upset that saw her running nearly every two minutes to use the toilet.

Imoke is from Ekureku, a rural community in southern Nigeria’s Cross River State. At first, he felt his wife’s ailment was nothing serious and could be self-managed.

“I did not know what was wrong with her. So we managed and got her drugs from the chemist (a local patent medicine store),” he said, fighting back tears. “She was always rushing to the toilet and sometimes found it difficult to eat.”

On December 15, she became unconscious. It was then Imoke rushed her to the community’s public health centre. Unfortunately, she died that night at the hospital.

Two days later, his eight-year-old eldest son, Daniel, also died. The clinic confirmed to the family that they both had cholera, an acute diarrhoeal infection partly caused by the consumption of contaminated water.

Imoke’s wife and son were among 51 people who died from a cholera outbreak in Ekureku within that period, according to Bernard Egbe, a local chief in the community.

Data from the Nigerian Center for Disease Control or NCDC show that cholera claimed about 233 lives across the country from January 1 to September 25, 2022. The December outbreak in Ekureku only pushed the 2022 cholera casualties higher. But the NCDC has yet to update its data to reflect the December deaths.

NCDC attributes the spate of the virus to “limited access to clean water and sanitation facilities, open defecation and poor hygiene practices.”

The people in Ekureku rely on a stagnant, contaminated stream for drinking and other domestic uses. Generally, only 25.7% of Nigeria’s 213 million population has access to clean drinking water, with 39% of households in rural communities like Ekureku lacking access to essential water supply.

“Access to clean water is the first and most viable line of defence for rural dwellers against the virus,” Felix Ukam, executive director of the Centre for Healthworks, Development and Research Initiative or CHEDRES, a non-profit based in Calabar, the Cross River State capital, told Prime Progress.

State government’s failure contributed to deaths

The 51 deaths in Ekureku would probably never have happened if a Cross River State government-led water project meant to provide clean water to villages in Ekureku was not abandoned in what some say was due to corruption.

In 2012, the Nigerian federal government requested from the World Bank a credit facility of $120 million to implement the Second National Urban Water Project in Lagos and Cross River states.

The credit facility, secured by the federal government on behalf of the states, and financed by the International Development Association or IDA, an institution that offers loans and grants to some of the poorest nations in the world, was a loan to the federal government and a grant to the states.

In Cross River, this money was meant to extend and upgrade facilities for public water supply to three local government areas, including Abi, where Ekureku is. The implementing agency was the State Water Board Limited.

The state’s 2015 audited account shows that from the $120 million and subsequent loans the federal government got from the World Bank, Cross River got a whooping N16 billion to provide clean water to communities across the state. But the contract included a 15% counterpart fund of N55,000,000 from the state for each of the two years the project was expected to last (2014 and 2015).

In 2014, the state government awarded the contract for the Itigidi, Adadama and Ekureku water scheme to Lilleker Brothers Nigeria Limited, a local company. The contract, valued at N1.3 billion ($8.2 million at the time), was meant to provide pipe-borne water to about 5500 homes within the communities.

While awarding the contract, Liyel Imoke, who was state governor then, reiterated the need for the project to “be pursued effectively and delivered on time” because “lack of potable water is responsible for poverty and other diseases.”

But nine years later, there is no proof that the project was ever pursued “effectively”, much less delivered. The contractor started the work but abandoned it and never returned to the site.

A staff member at the Cross River State Water Board, the agency directly responsible for the project, blamed its non-completion on the unwillingness of the new government of Governor Ben Ayade that came in 2015 to pay the agreed 15% counterpart fund.

“The new government, for some reason, saw no need to continue to pursue the project, so it didn’t pay the counterpart funds. The Obubra and Okpoma water projects were also affected,” the female staff, who is not authorized to speak to journalists, said.

The 2015 audited account confirmed that the government failed to pay the funds, thereby short-cutting the project. Besides, there are indications that even the money from the federal government might have been misused in corrupt ways, the reason the government never followed up on the contractor to complete the project.

Efforts to get the managing director of the water board, Victor Ekpo, to explain the situation behind the project abandonment met a brick wall. A letter Prime Progress sent to his office on January 11, 2023, was not responded to, despite two follow-ups. He did not also reply to a text message sent to his known phone number.

Lilleker Brothers Limited, the company that won the contract for the project, was not available to comment. The company’s office inside the state’s water board compound in Calabar is now deserted and locked.

Pipes without water

While the government keeps mute, the project’s halting has left the people in the communities helpless and defenceless.

“Our major challenge here is water. It’s worse during the dry season, and our people have to go through hell for water. We are helpless,” said Eval Ezege Eleng, the clan head of Agbara, a village of 5000 people and one of several that make up the Ekureku community.

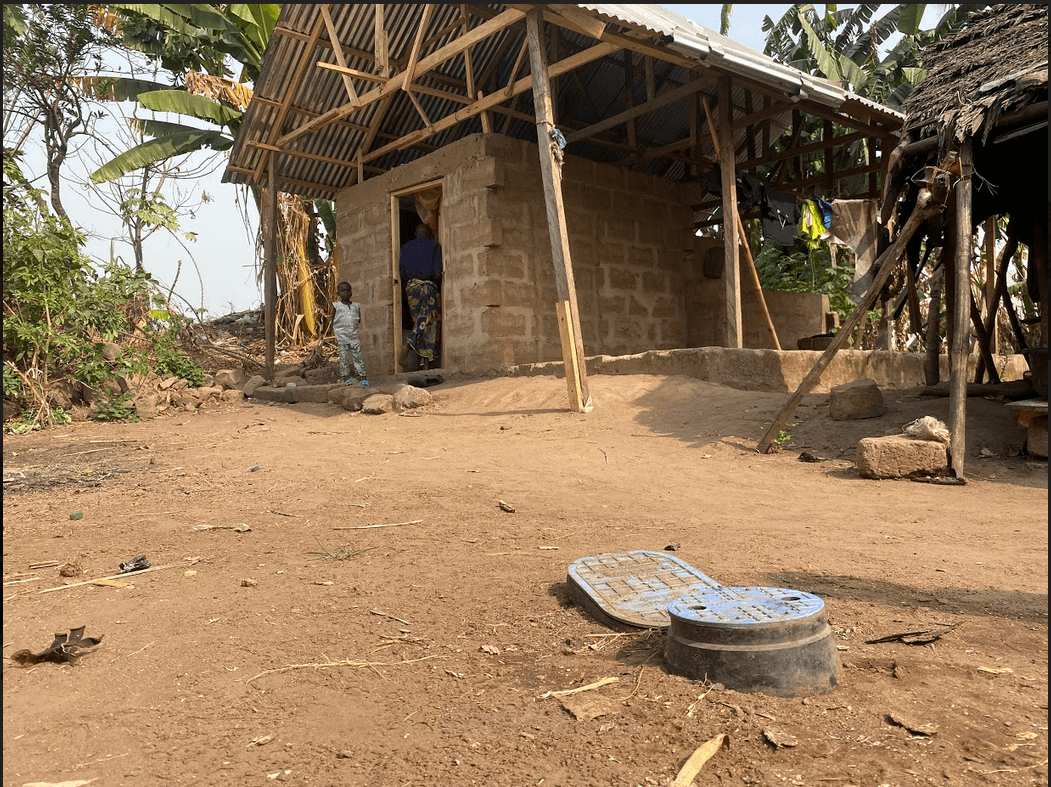

“It is a terrible situation. I still remember when they came to install the pipes and how hopeful everybody in the village was. We know what we go through, especially in the dry season, because of water. But they (the workers) just disappeared after laying the pipes.”

Joseph Enya is a local farmer. His compound holds proof of what could have been but never was. There are pipes running from one end to another into a standing water pump that is unfortunate never to have carried water.

“They came here from the state waterboard and installed all these pipes, and then they disappeared one day without a single drop running from it,” he said.

Enya himself is a survivor of the cholera outbreak in the community. Now, he fears that if nothing is done about access to clean water for the community, “it [cholera] will come back. Our people need clean water, and I don’t think we are asking for too much,” he said sorrowfully.

EKUREKU, CROSS RIVER: On December 14, 2022, Eleng Orji Imoke faced a devastating tragedy when his wife fell seriously ill and succumbed to cholera the next day. Shortly after, his eldest son, Daniel, also died from the same infection. Their deaths were part of a cholera outbreak that claimed 51 lives in Ekureku, Cross River State.

The outbreak was linked to the community's reliance on contaminated water sources. Despite a significant funding effort by the Nigerian federal government and the World Bank to improve water supply in the region, the project was abandoned due to corruption and lack of commitment by the state government. The 2012 initiative aimed to provide clean water to communities in Cross River State, but the project never reached completion, leaving the villagers without essential water access.

The Cross River State government failed to provide the necessary counterpart funds, leading to the abandonment of the project. This dereliction of duty by successive governments has left the community struggling with inadequate water supplies, particularly in the dry season. The pipes installed during the project remain dry, symbolizing the unfulfilled promise of the initiative.

Community members, including local farmers like Joseph Enya, who survived the cholera outbreak, continue to plead for clean water to avert future health crises. The lack of response from relevant authorities exacerbates their plight, leaving them vulnerable to recurring outbreaks and highlighting the urgent need for reliable water infrastructure.