It was January 3, 2024, and Zampa village in northern Taraba State was still abuzz with the new year’s celebrations. Farmers who suffered shrinking harvests in the last season joined those with bountiful harvests, thankful for the gift of another year. These jubilations wouldn’t last for long, however.

A little after 1:00, around midnight, armed kidnappers stormed the village, in the company of villagers they had abducted from nearby communities. Upon arriving at Zampa, they split into three groups, all in search of Halima*, a community health extension worker, or CHEW, at the Zampa Health Post. One surrounded Halima’s house, another forcibly entered, and a third held down the abducted group.

All efforts to capture Halima were futile. Frustrated, the kidnappers turned on her neighbors, demanding Halima’s whereabouts. But the neighbors, who were gripped by fear, didn’t know about Halima. They asked about Halima’s daughter, who was among the people crouching in fear, but no one could point her out.

The kidnappers went to the village’s health facility on the prowl again. Yet Halima remained elusive, however hard they searched. As they departed, they whipped some of the villagers as if to avenge Halima’s absence.

Fearing the kidnappers’ return, many Zampa residents, women and children especially, fled to Jalingo, the state’s capital, the next morning. Similar attacks were reported in neighboring villages like Wuro Musa and Lanko, all nestled in the northern part of Taraba State.

On the night that the kidnappers struck, Halima was away on a break, having left for Jalingo shortly before Christmas. Hearing about the ordeal and how the kidnappers had been on her prowl, she stayed far from Zampa.

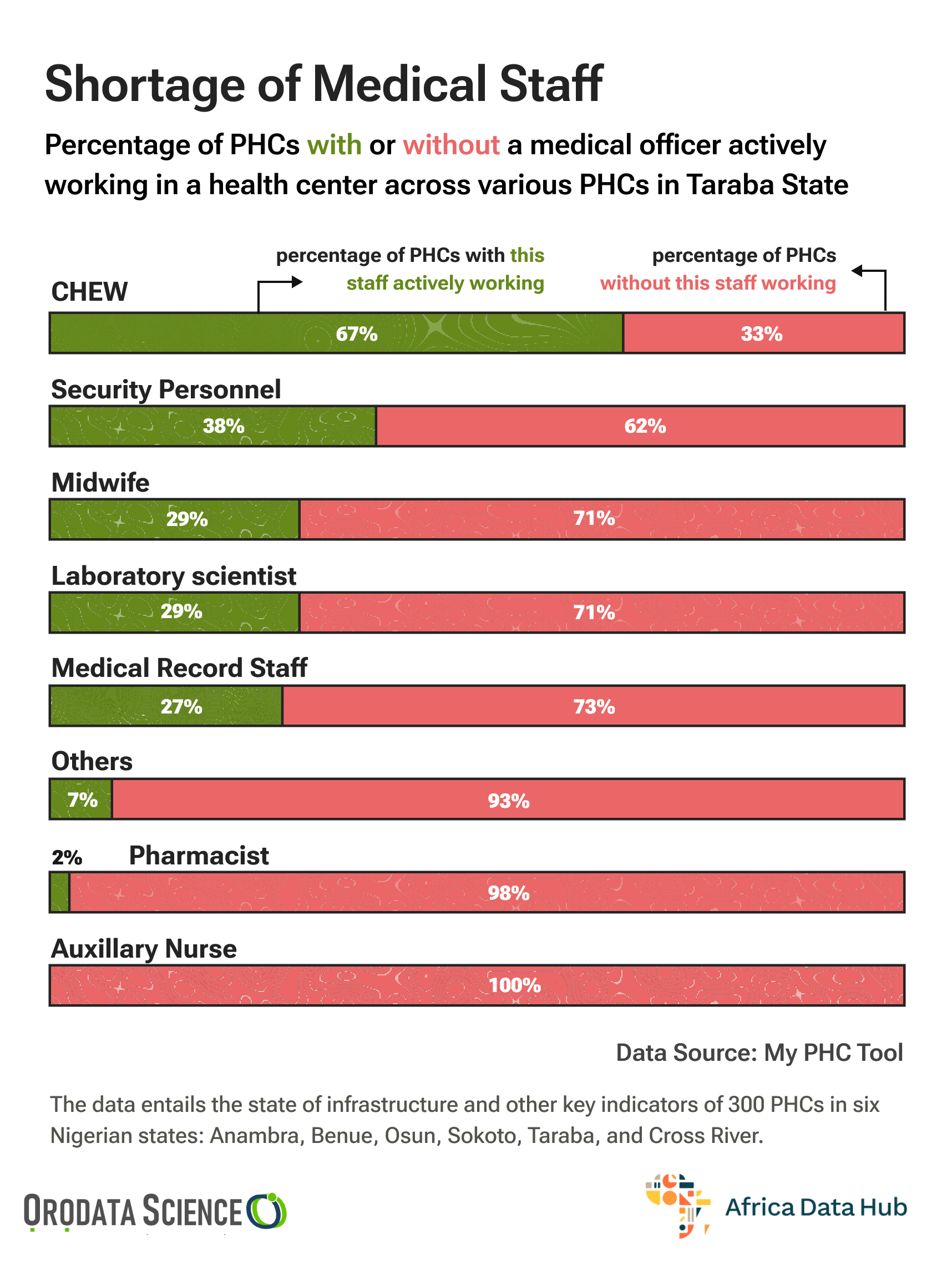

Halima’s case is hardly an isolated incident of healthcare workers targeted for violence. Earlier in 2018, gunmen abducted 3 healthcare workers of the Taraba State Primary Healthcare Development Agency, or TSPHCDA, who were busy on a data collection project in southern Taraba, as reported by the PUNCH. In 2019, two more doctors were kidnapped, prompting the Taraba State chapter of the Nigerian Medical Association to demand intervention from the state government.

Continued abductions have caused distress among healthcare workers, leading many to raise alarms about the prevailing insecurity.

Failing Healthcare

As gathered from locals, the health facility in Zampa was built in 2007 as a hut by community members. Without qualified personnel, the facility struggled with basic healthcare services until three years later, when the Taraba State Government reformed the hut into a bungalow with three rooms. Afterward, Halima was assigned by the TSPHCDA as the head of operations at the reformed health center.

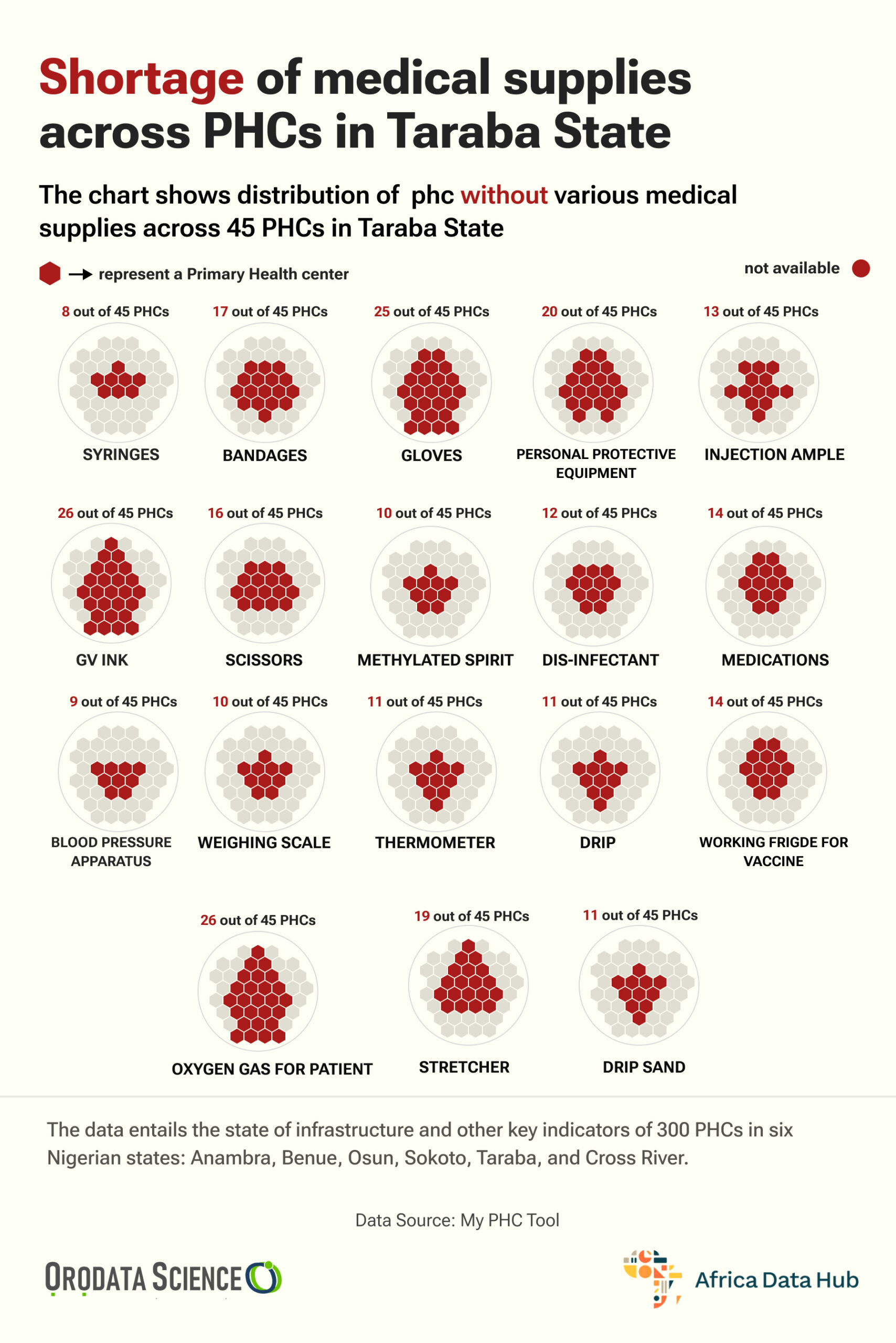

After assuming duty at the facility, Halima took on the task of vaccinating children in Zampa and six neighboring settlements against polio and cholera. At the same time, she enjoined expectant mothers to subscribe to antenatal care. Yet many of the services she pushed for were hindered by a gross lack of adequate equipment in the health center.

“I was transferred from another PHC to come here and despite our efforts to make things work smoothly, we still failed, due to shortages of staff and medical equipment in the facility,” Halima said.

Worried by the seeming lack of progress at Zampa Health Post, Halima, in 2014, left for another healthcare facility, and things turned even worse for Zampa Health Post. Seeing the gap left by Halima’s departure, Zampa’s community leaders rallied to get her back to the facility. By 2017, after persistent lobbying, Halima returned to her former health outpost.

“After she left, we couldn’t find someone that matched the work she was doing for us. So we put efforts to see her return,” said Jauro Musa, the community head of Zampa.

Despite a shortage of manpower, Halima plowed ahead with her medical service until December 2023, when she took a break before the kidnappers invaded.

“Sometimes, I would use my funds to travel to Jalingo and source medication for the community members. I have forwarded complaints to authorities several times, but there wasn’t any change,” Halima recounted.

Scared

In the wake of the kidnapping incident, many locals have fled Zampa. While many others visit their farms in the day only to return secretly to Jalingo by night.

“There are only a few remaining here and our nights are spent worrying about our husbands, who are forced to sleep in trees for fear of being abducted. Everyone is afraid. We think they might come back and take some of us,” Rashidat Yusuf, a resident of Zampa, told Prime Progress.

Locals in Zampa have expressed worry over the fact that their settlement will never be as peaceful and rustic as before. Their anxiety is goaded by stories of people kidnapped for ransom in nearby settlements.

The spate of kidnappings in Zampa and neighboring communities has continued without any significant intervention from the authorities, leaving villagers vulnerable and depressed. Their lives seem to hang in the balance, as most of the locals expressed.

One morning in January, as Hafiza Mubarak lay in bed, a sharp pain gripped her around her pelvis. She was just five months pregnant.

“The pain was intense, and I was subsequently transported to a hospital in Jalingo, where I stayed for three weeks before regaining my health,” the 28-year-old narrated.

Given that the Zampa Health Post was derelict and bereft of quality medication, Mubarak made the arduous trip to Jalingo for medical care instead. This is Mubarak’s second pregnancy. As with her first, Zampa’s deplorable healthcare center leaves her with no access to prenatal care.

The health facility, a single-story bungalow, consists of only three rooms. Inside, a waiting room offers a modest welcome with just a few old chairs. To the left lies the ward, containing two broken beds with shabby mattresses. On the right is Halima’s office, which doubles as a storage room for the scant medical supplies.

The toilets stand a few meters away from the main building, two narrow rooms designated for males and females. Its creaking doors and overgrown weed greet visitors before the rank smell of urine that assails the nostrils. The cistern doesn’t work.

As there are no boreholes within its surroundings, the facility relies on water from a stream about 650 meters away.

According to the Thehospitalbook website, Zampa Health Post offers antenatal care and six other medical services for in-patients and out-patients. However, this reporter’s findings revealed none of the listed services to be fully provided.

This reporter also observed, during the investigation, that the facility falls short of some basic requirements outlined in the National Primary Healthcare Development Agency’s minimum standards for primary healthcare centers.

According to Chapter Four of the minimum standard for Primary Health Care in Nigeria, the health post (which ranks lowest on the cadre) should be a detached building with at least five rooms in good condition, including functional doors, netted windows, and separate, functioning male and female toilets with running water on-site.

The building must also have sufficient rooms and space to accommodate a waiting or reception area, client observation area, consulting area, delivery room, pharmacy section, record, and staff section.

Also, it must be signposted and visible from both entry and exit points. The facility must also be fenced with a secure gate and include a generator house for uninterrupted power supply.

Not returning

Following the attacks, Halima disclosed to Prime Progress that she would not return to the facility.

“I feel like I’m being targeted. It’s important to take precautions to protect myself. The possibility of my return depends on the proactiveness of the authorities in taking necessary security measures and also equipping the facility with essential medical equipment,” Halima bemoaned.

While Halima chose to embrace the comfort of her home, uncertainty looms over the future of Zampa Health Post.

A staff member at the TSPHCDA who asked to be anonymous revealed that the agency was taking steps to address the insecurity at Zampa Health Post.

Until the authorities intervene, countless women like Mubarak will continue to grapple with insecurity and a lack of essential healthcare services.

*Name changed to protect the subject’s identity.

This story was produced for the Frontline Investigative Program and supported by the Africa Data Hub and Orodata Science.

On January 3, 2024, the village of Zampa in northern Taraba State was disrupted by armed kidnappers searching for Halima, a community health worker. Despite their efforts, Halima was not found, and the kidnappers instead terrorized her neighbors and destroyed medical equipment at the local health post.

Fearful for their safety, many residents, especially women and children, fled to the state capital, Jalingo. Similar attacks were reported in neighboring villages. Halima was away in Jalingo during the attack and decided not to return to Zampa due to fears for her safety.

This incident highlights the ongoing targeting of healthcare workers in Taraba State, with previous abductions reported in 2018 and 2019. The Zampa Health Post has struggled with inadequate facilities and staff since its inception in 2007, despite efforts by Halima and community leaders to improve conditions.

Since the attack, the health post remains under-equipped and unable to provide essential medical services, forcing patients to travel great distances for care. Without significant intervention from authorities, the safety and well-being of Zampa's residents remain in jeopardy.

This story underscores the urgent need for better security and healthcare infrastructure in rural areas.