PORT HARCOURT: Ben Arikpo and his wife, Felicia, became worried in 2010 when they realised their eight-year-old son found it difficult to spell, identify some letters of the alphabet, and read simple sentences.

In December 2011, while on a one-month family vacation in the US, Arikpo took his son to a brain assessment and training organisation, where he was diagnosed with dyslexia, a learning disorder that makes it hard for individuals to learn, read and comprehend.

Though Arikpo was teaching sociology and applied psychology at the University of Calabar, Cross River State, at the time, he had never heard of dyslexia.

He was not alone.

Despite dyslexia being the most common learning disability affecting one in every five people in the world, with 70 to 85% of children with learning disabilities having dyslexia, knowledge of the disorder is low here.

“My son was diagnosed with dyslexia in 2019 at the age of 25, and before that time, I did not know such a condition existed,” said Alhassan Aliyu, a 61-year-old engineer in Minna, Niger State.

Further screening on Arikpo’s son revealed that the boy also had attention deficit hyperactivity disorder or ADHD. This nerve-related disease makes people easily distracted, have difficulty paying attention, and slows their brains’ capacity to process information.

At least 30% of people with dyslexia also have ADHD, according to the International Dyslexia Association.

A strange dream

Following the assessment, experts at the organisation asked Arikpo to pay $35,000 (N16 million), so the boy could undergo brain training therapy for one year to strengthen his weak cognitive system.

“But I didn’t have the money,” Arikpo said. Meanwhile, “[As] I was walking away in frustration, someone said, ‘by the way, we’re selling franchises to the rest of the world in case you’re interested.”

That idea did not sound like what Arikpo, a pastor with the Redeemed Christian Church of God, would be interested in. After all, the franchise cost was $50,000, $15,000 more than the training fee for his son.

However, weeks later, “I had a dream that showed me a million children in a stadium; I was trying to liberate them, and I was shouting, ‘let them go.’ My wife woke me, and I told her about the dream. Then she said, ‘that franchise’ is not just for your son,” Arikpo narrated.

For some strange reasons, he agreed with her that what he saw were dyslexic kids in Nigeria seeking help because, at the time, there was no group certified to treat dyslexia in the country.

When Arikpo returned to Nigeria, he took a bank loan and paid for the franchise. The acquisition process took two years. During this period, the franchising organisation trained Arikpo and his wife on how to conduct dyslexia tests, the tools to use, and the brain training after assessment.

In 2013, they opened a dyslexia assessment and brain-training facility in Abuja; their son was their first patient.

With assessment tools like Gibson and ARX, the couple and others working with them can assess a dyslexia case and determine the appropriate training method.

“For the Gibson test, we take the information from parents [details about their kids’ condition] and put them in the system (computer), and then we set up the system to test questions. The system shows you a picture; for instance, there’s a car of a particular colour and a dog on top of the car. Or a dog beside the car, and then it turns to the next page and says, ‘which of these dogs was in the car?’ Or ‘which of these dogs was beside the car?’ Just to see how you remember stuff?” he explained.

“Then we print out [the result], and from there, it shows us an intervention approach which might take nine months, six months, one year as the case may be.”

The ARX, a less complex computer-based simulation test, is used “[When we set] the Gibson test, and you’re unable to do it no matter your age, that shows your cognitive skills are below five years old,” Arikpo said.

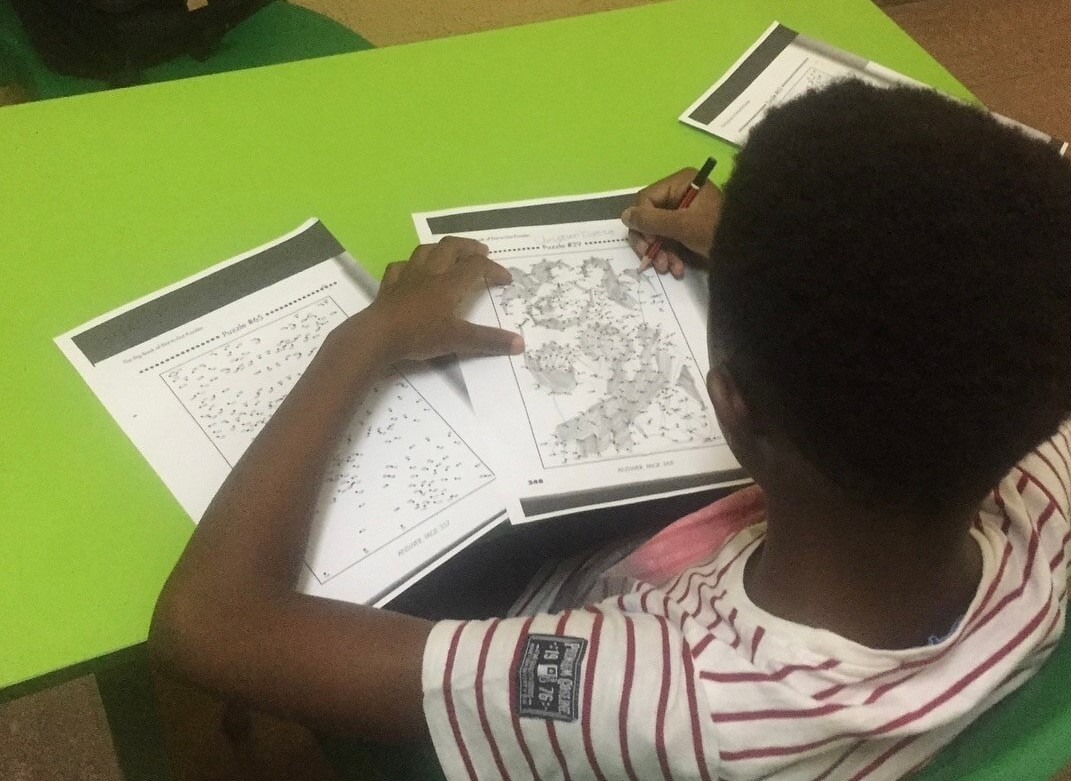

Once the assessment is concluded, the proper brain training begins, involving one-on-one sessions with an instructor and several digital exercises.

For example, for a child struggling to concentrate due to ADHD, an instructor takes them through an exercise involving the child using a computer to carry out tasks that look like they are playing a game but are not actual games.

The instructor attaches a brain-sensing headband to the kid’s heads to measure their speed and accuracy in completing those tasks. The child improves with the repetition of these exercises over weeks and months.

“For all those deficiencies, there are digital and one-on-one exercises that we take them through,” said Arikpo, adding that the aim is to help the individual improve their attention processing speed, auditory processing speed, and visual, long-term and working memories.

Through this process, within six months, Arikpo’s son improved in his learning ability: he could identify letters and attempt to read simple sentences better and spell words he could not.

Reaching other kids

Arikpo’s son remained the facility’s only trainee until 2015, when the couple visited some special schools in Lagos and sought approval to tell parents about the impact of dyslexia and the need for the brain training program for their kids.

In April 2015, they founded a social enterprise, the Dyslexia Foundation Nigeria, to create awareness about dyslexia and ADHD using radio and television talk shows and awareness walks to encourage parents to bring their dyslexia-sick kids to the facility for assessment and training.

The social enterprise charges N100,000 ($227) per assessment, which Arikpo insists is subsidised compared to between $1,500 and $5000 (N666,000 to N2,220,000) charged in the US and other countries.

Besides the assessment fee, parents pay more for the proper training, which could run for six months, a year, or even longer, depending on case severity determined by the foundation’s psychologists.

The cost implication, however, poses a limitation; less than 20% of about 1000 kids the foundation has assessed since 2015 have gone through training. Most parents here cannot afford the cost.

According to Arikpo, the service is cost-intensive, and the foundation cannot give it entirely free. But parents whose children have undergone the training say they are happy with the outcome.

“My [17-year-old] daughter was assessed in January 2020 and underwent the training. We began to see results after about a year. She began to write, spell, and read well. Those things used to be very difficult for her,” said Lagos-based Theresa Unaam.

“My son has developed self-confidence and can read, write, and comprehend better,” adds Aliyu, the 61-year-old engineer whose son started training in January 2020.

Zero legal protection

Arikpo said the foundation now has two extra centres, one in Lagos and another in Port Harcourt. Still, he worries that Nigeria has no legislation explicitly protecting people with dyslexia, unlike countries like the US, which has 33 legislative bills on dyslexia.

Where such laws exist, they mandate schools and test organisers to give kids with dyslexia additional time to complete their tasks during tests, examinations, and other controlled brain-tasking activities.

“The disability act in Nigeria does not mention dyslexia anywhere; the nearest definition is ‘people with intellectual disability’, and dyslexic children are not intellectually disabled,” Arikpo lamented.

The absence of such laws in Nigeria means schools do not bother to train teachers to manage kids with dyslexia, and 90% of the country’s teachers do not know about the condition.

Arikpo’s foundation now trains parents, teachers, and school administrators on teaching and caring for dyslexic children.

Despite challenges, however, Arikpo said he is proud that his decision to get a franchise has helped his son and many other kids. His son is now in his second year at a Nigerian university Arikpo prefers not to mention. He copes comfortably with his parents’ continuous support.

This story was produced with the support of Nigeria Health Watch through the Solutions Journalism Network, a nonprofit organisation dedicated to rigorous and compelling reporting about responses to social problems.

In 2010, Ben Arikpo and his wife realized their son had learning difficulties, leading to a diagnosis of dyslexia and ADHD during a US vacation in 2011. Despite Ben's background in sociology and psychology, he was unfamiliar with dyslexia, a common learning disability affecting many globally. Faced with the high costs of therapy, Ben pursued a franchise opportunity, inspired by a dream to help millions of children. Returning to Nigeria, he started the country's first dyslexia assessment and brain-training facility in Abuja in 2013.

The facility uses advanced assessment tools like the Gibson test and ARX to tailor training methods. Despite initial financial challenges, their son showed significant improvement. To reach more children, the Arikpos founded the Dyslexia Foundation Nigeria in 2015, raising awareness through media and public outreach. They now charge a subsidized assessment fee but face limitations as most parents can't afford the full training costs.

Arikpo's advocacy extends to training educators about dyslexia, highlighting the lack of legal protection and support in Nigeria compared to countries with dedicated dyslexia legislation. Despite challenges, his efforts have positively impacted many children, including his son, now a university student. The foundation's work continues to address the significant gap in dyslexia awareness and support in Nigeria.

This story was produced with the support of Nigeria Health Watch through the Solutions Journalism Network.