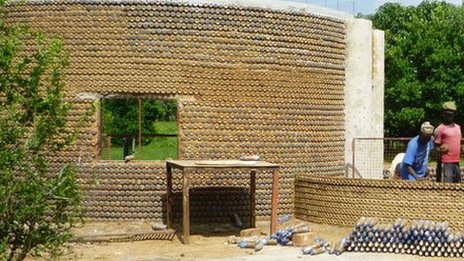

In the blistering heat of Abuja’s Jahi district, 34-year-old construction worker Ibrahim Musa mops sweat from his forehead as he stacks long cylindrical bottles into a wall. Each plastic bottle is filled with sand and serves as a building block for a housing project.

“People used to laugh at us,” Musa says with a chuckle. “They said, ‘How can you build a house with bottles?’ But when the first room stood firm after heavy rain, they came back and asked for one like it.”

The rise of eco-bricks

Nigeria churns out an estimated 2.5 million tonnes of plastic waste annually. Of these, less than 10% is recycled; most ends up clogging drainages and forming litter on streets. Amidst this, an environmentalist movement is attempting to transform plastic waste into sturdy, affordable homes.

Referred to as eco-bricks, these plastic bottles are tightly packed with sand and then stacked and held together with mud or cement just like regular blocks.

The concept is not entirely new. In 2011, the first plastic-bottle house—a two-bedroom bungalow—was erected in Kaduna by the Development Association for Renewable Energies (DARE). More than 7,800 bottles were used for the project.

More than a decade later, ecobricks are gradually drawing fresh appeal—in the face of Nigeria’s critical housing shortage. The Federal Mortgage Bank of Nigeria (FMBN) estimates that more than N21 trillion is required to bridge the deficit.

Other factors are also at play. The concept of plastic houses thrives off the rising costs of building materials, reckons Sarah Nwankwo, an architect with Ecobuild Nigeria, a construction firm that specialises in sustainable housing solutions.

With the cost of materials such as cement soaring in recent years, leading to knock-on effects for the average Nigerian, “plastic waste offers a low-cost and environmentally responsible alternative.”

These structures boast surprising durability. “We ran a stress test on one wall,” recalls Nwankwo, referring to a plastic-made building. “It took the impact of a sledgehammer without cracking. Try that with regular cement blocks.”

They also boast ample environmental benefits, providing insulation against blazing temperatures and the harmattan chill compared with brick buildings.

Plastic reuse is not limited to only houses. In 2021, the Federal Ministry of Works and Housing, in partnership with BAS Plastics and Dantata Construction, tested the country’s first plastic-paved road using recycled polymer waste.

Despite its broad applications, not everyone is sold on its sustainability. “We need to test for fire resistance, long-term durability, and how these houses respond to Nigeria’s high humidity,” notes Ifeoma Eze, an environmental scientist at the University of Abuja.

Besides, she adds, Nigeria’s undeveloped recycling infrastructure means that “collecting, sorting and cleaning enough bottles for just one house can take weeks.”

Musa, the construction worker, believes the challenges are overstated, however. “People bring bottles to us from dumpsites. Some get paid; others just want their environment clean,” he says. According to him, his team of six completed a two-room structure at half the cost of a cement-block home.

For all its promise, social acceptance remains a hurdle. Many bottle houses are dismissed as substandard, making it difficult for owners to obtain land titles or permits. This also means difficulty in securing bank loans. Musa recalls a bank manager’s reaction while applying for a mortgage using his plastic home as collateral. “He said, ‘Come back when you’re building with real materials.’”

Scaling the plastic-housing movement

States are leading efforts to foster awareness and increase adoption. In Kaduna, where Developmental Associations for Renewable Energy (DARE) continues to promote eco-bricks, state authorities have expressed interest in using plastic for public toilets and rural classrooms.

Also, Lagos State’s Ministry of Environment is exploring partnerships with recyclers to pilot similar models in low-income areas like Makoko and Ajegunle, where high rent and flooding make conventional construction nearly impossible.

But scaling the idea, Musa admits, will require policy backing. “For now, each house is a kind of prototype,” he says. “Until there’s support—maybe tax incentives for green builders or inclusion in public housing programmes—it will remain mostly experimental.”

The United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) recently identified Nigeria as one of Africa’s frontline innovators in plastic reuse, citing its potential to align with the UN Sustainable Development Goals.

Whether Nigeria’s plastic-housing movement becomes a cornerstone of sustainable development—or remains a visionary experiment—will depend on how quickly policy, perception and technology align.

Summary not available at this time.