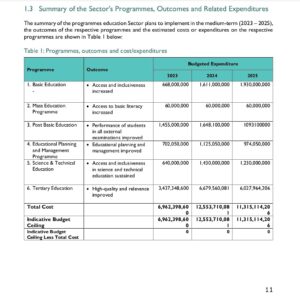

In 2022, the Adamawa State government sought support from the United Agency for International Development (USAID) through its State2State project to implement a five-year Medium Term Development Plan targeting critical areas such as education, health and water, sanitation and hygiene (WASH). This plan also led to the Medium Term Sector Strategy (MTSS), billed to run from 2023 to 2025 and seen as a link between the development plan and the state’s annual budget.

Although subject to annual review, the 3-year MTSS ensures that the objectives and strategies outlined in the education sector of the Development Plan are achieved. Ahmadu Umaru Fintiri, the state governor, hailed the strategy as a significant shift from traditional budgeting procedures to a result-oriented planning aligned with contemporary practices. Similarly, Wilbina Jackson, the former Commissioner for Education and Human Capital Development, noted that the MTSS focused on five core objectives for education aligned with global policies.

Among the key targets of the MTSS are: boosting school enrollment in Adamawa from 86% to 95%; ensuring that all kids in the state attain basic education by 2025; repairing dilapidated school infrastructure; distributing sports and WASH facilities to schools; providing essential textbooks for students; and improving adult literacy and numeracy rates past 75%.

Additionally, the MTSS outlines plans to spend more on teacher recruitment and salaries, thereby improving the ratio of students per teacher.

Given that it establishes a theoretical connection between governmental structures and functions, particularly in relation to gender equality in education, gender-responsive education sector planning, or GRESP, is regarded as the cornerstone of Nigeria’s state education sector planning.

At its core is an advocacy for the creation of policies and opportunities that meet the specific needs of each gender. The GRESP draws on numerous research studies that have highlighted the inadequacies of Nigeria’s educational policies.

For all its merits, the MTSS fell short on addressing gender-specific educational needs as outlined in the Gender-Responsive Education Sector Planning (GRESP), highlighting a broader flaw in Nigeria’s educational policies.

Obstacles to girls’ education

A UNICEF factsheet from 2022 reports grim statistics about girls’ education in Nigeria. About 3.9 million girls are enrolled at the primary level and 3.7 million at the junior secondary level, with 7.6 million out of school. At least more than 50% of girls reportedly do not attend school at the basic education level. Where 1 million girls within each cohort are reported to drop out between the first and last year of primary school, 600,000 drop out between Primary 6 and JSS1. The UNICEF report also shows that the northeast and northwest regions account for nearly half of the girls that are out of school in Nigeria.

Additionally, data from the UNESCO Institute for Statistics revealed that only 42% of girls in Nigeria transitioned to secondary school after primary schooling, according to a report by the Center for Advocacy, Transparency and Accountability Initiative (CATAI). Invariably, 58% suspend their education after primary school.

In Adamawa, 51% of girls aged between 12 and 15 never attended school, while a staggering 62.5% were out of school, according to a joint analysis by UNESCO and the World Bank, published in 2021. A Joint Educational Needs Assessment (JENA) dating back to 2019 highlighted that only 20% of schools in Adamawa boasted adequate furniture. This shortfall in resources, together with potential gender biases, is considered among the chief reasons for the poor enrolment of girls in schools across Adamawa.

Negative impacts of educational disparities on girls in Adamawa

In October 2024, this reporter visited public schools—mixed and girls-only—across Adamawa, noting a myriad of challenges. At Government Girls Day Senior Secondary School in Ganye, for example, students complained about dilapidated toilets and inadequate classroom chairs.

“Students used to go around [open spaces] to shit,” said Sakinatu*, one of the students. The school’s first aid box lacked even basic medications such as paracetamol. “The Always [referring to sanitary pads] is already finished inside the first aid box. Sometimes, the school management goes outside to buy the Always. But now there’s not even one in the school,” continued Sakinatu*.

Another student, Jessica*, admitted that she was forced to stay at home during her menstrual period because of the lack of adequate sanitary pads at school. Yet more bothersome for her is the library, which contains few books for students to study when their teachers are away.

“We don’t have labs for practical subjects like chemistry, physics, and computer science. This is my biggest challenge, and it’s depriving me of a quality education,” she said with mounting frustration.

A staff member of the school said that these challenges stemmed from an inadequate GRESP budget for conducive classrooms within schools. She noted that students in the school suffer unbearable heat, especially in April. “There are no ceilings. Because of this, the students don’t concentrate. No matter what you will do to try to calm them, they will not concentrate. They will be there fanning themselves. Their attention will not be in the classroom. They want to go out and have ventilation. Sometimes, when it’s too much, we just ask them to go,” she explained.

In the same vein, students from Government Girls Science Secondary School in Mayo-Belwa expressed dismay over their dilapidated hostels and toilet facilities.

Formerly a boarding school, its junior school was turned into a day school two years ago. The transition created new problems for the school management, who now had less control over the day students, said one female teacher.

“The major factor hindering effective GRESP implementation is the large number of students,” the teacher emphasised. “We don’t have enough classrooms, and it hinders us from achieving the objectives of our lessons. The teachers are also very few, especially in the junior secondary school, which is affecting some of the subjects. That’s to say that we cannot achieve the aim we intend to achieve at a particular time.”

Education advocates contend that GRESP budgeting in schools must include functional toilets outfitted with continuous flow of water as well as a pad bank. “Gender-responsive education has to see the provision of good infrastructure that girls need. Unless this is done, we can’t say we have free and gender-responsive education in Adamawa,” explained Dr. Hassana Shuaibu, a senior programme officer at ACE Charity, a non-profit organisation supporting development in Africa through access to quality education and economic opportunities.

The Adamawa State Ministry for Women Affairs and Social Development reinforced its commitment to partner with schools in order to tackle sexual gender-based violence (SGBV) in the state and ensure that perpetrators are punished. However, the ministry was not involved in either the development or implementation of the MTSS “because we have the ministry of education, which is responsible for that,” its commissioner, Neido Kofulto, said. “And also when we are invited to it, depending on the situation.”

Teachers and students who spoke to this reporter attributed the challenges to poor funding or a complete lack of effective incorporation of GRESP components in the education budget. When presented with these concerns, the Ministry for Education and Human Capital Development, responsible for implementing most of the key priorities and targets of the MTSS, responded that a significant chunk of the state budget was allocated to education in 2024. “We have factored gender-responsiveness in that,” added the ministry’s commissioner, Dr. Garba Umar Pela.

An analysis of the Adamawa State Education budget by CATAI revealed that only 11% of its overall approved budget of N175 billion was allocated to education. This was down 5% from 16% in 2022, with the 2023 education budget of N20 billion paling in comparison with the previous year’s N27 billion.

CATAI also noted that the gender responsiveness of the education budget remains difficult to assess owing to the lack of specific line items detailing how funds were utilised. This makes it challenging to evaluate the budget’s focus on gender-related needs.

Furthermore, CATAI highlighted minimal funding as a primary challenge encountered during the budget analysis. Less than 70% of the funds were eventually disbursed to the educational sector, creating negative impacts on educational outcomes in the state.

The 2024 proposed budget by the Adamawa State government for 2024 is N225.8 billion. Of this, N15.3 billion, later increased to N21.2 billion, was allocated for education. Notwithstanding the increase in allocation, findings showed that only N3.3 billion was released between January and June, a marked contrast to the approved 20% in the state budget.

Yet experts maintain that adequate funding is crucial for the implementation of gender-responsive education in Adamawa. “The budget has to be there because it isn’t about doing fantastic plans. if it’s not incorporated into the budget, then nothing will happen,” said Hassana of ACE Charity. “And it’s not also about budgeting, it’s about releasing [the funds] as well.”

Hassana stressed the need for strong political will to implement GRESP effectively. She remarked that to promote accountability and ensure government ownership, it is important for government institutions to actively participate in the process of developing the GRESP, rather than solely relying on non-governmental organisations.

“All relevant stakeholders in the state need to be aware of what’s going on and what role they are going to play. There should be transparency and accountability mechanisms to track where the money is going,” she said.

A call for action

A member of the Adamawa State Parents Teachers Association (PTA), who requested anonymity, said that essential sanitary facilities for girls need to be provided in schools. “Sanitary pads should be in schools where there are girls. Their menstrual cycle comes instantly without notice or being planned for,” he explained, adding that the government should involve the PTA in planning the education budget to ensure that the needs of students for safety, health, and effective learning are addressed. This includes providing necessary sanitary facilities and infrastructure.

Teachers at the Government Science Secondary School in Mayo-Belwa reported that, despite strong academic performance, parental neglect hinders girls’ education.

“They [parents] don’t care much about the education of the girls,” one teacher said. The teachers urged the government to allocate resources and manpower to educate parents about the importance of girls’ education. “The Adamawa State government is indeed prioritising education, but we want it to do more by allocating separate funds for girls education so as to improve the education of girls in the state,” a couple of teachers told Prime Progress.

One teacher at the Government Girls Junior Science Secondary School in Mayo-Belwa pressed for the allocation of a higher chunk of the education budget to GRESP components.

“Even 60% or 50%. It shouldn’t be less. The classrooms aren’t enough. You will see 80 students in one class, and it’s not conducive. We need enough classrooms so that we can keep a class at 40 students only. This will improve learning outcomes,” she voiced out.

Her advocacy chimes with widespread calls from the schools visited in Ganye and Mayo-Belwa urging the government for more sanitary pads and improved facilities in the education budget. One student, however, urged the government for stable electricity in her hostel to help her study at night, citing security threats and long-water queues. “We want all these to be addressed,” she said.

The PTA member further emphasised the need for increased funding in the education sector, especially for GRESP components, to sustain girls’ education in Adamawa.

“If you go to Primary 1 or JSS1, you will see many girls enrolled, and towards the end of the school system, you will see most of them have dropped out. Why? Right from the budgeting, this can be taken care of, how you sustain them within the school system. If these are addressed, perhaps, the issue of girls dropping out from school to get married will be reduced,” he said.

As Dr. Hassana and other education advocates contend, girls’ education in Adamawa faces a precarious future without adequate funding for GRESP as well as accountability from the government. For many female students in the state, they can only hope that their needs will be addressed in the upcoming annual review of the MTSS.

Names in asterisks have been changed to protect identities. Teacher names have also been omitted at their request, as many schools in Adamawa received a circular from their superiors forbidding interviews with journalists.

This report was published with collaborative support from ImpactHouse Centre for Development Communication and System Strategy and Policy Lab (SSPL).

In 2022, the Adamawa State government partnered with USAID, through its State2State project, to initiate a five-year Medium Term Development Plan aimed at improving education, health, and WASH services. The plan resulted in a 2023-2025 Medium Term Sector Strategy (MTSS) for education, which intends to increase school enrollment, refurbish infrastructure, and improve teaching conditions. However, the plan falls short in addressing gender-specific educational needs, specifically the Gender-Responsive Education Sector Planning (GRESP) goals. Reports highlight that more than 50% of girls do not attend school, and 62.5% are out of school in Adamawa, compounded by inadequate facilities and poor teacher-student ratios.

Despite budget allocations, challenges persist in implementing gender-responsive education. The Adamawa education budget allocation decreased from 16% in 2022 to 11% in 2023, with less than 70% of intended funds released. This funding gap affects the realization of GRESP initiatives, such as providing sanitary facilities and improved infrastructure for girls. Teachers and advocates stress the need for increased budget allocations, strong political will, and accountability mechanisms to support girls' education and reduce dropout rates.

Educational disparities negatively impact girls, with inadequate sanitary facilities and infrastructures such as laboratories and chairs in schools. Teachers point out the need for a larger budget percentage dedicated to GRESP components, such as more conducive classroom environments and a consistent supply of sanitary pads. Both educators and advocacy groups call for the government to prioritize gender-responsive planning in the education budget to sustain girls’ education in Adamawa.