In November 2015, Virtue Olaitan Oboro found herself sitting in a hospital ward, her newborn son under the harsh lights of a phototherapy machine. He was battling neonatal jaundice, a condition that, if left untreated, can cause cerebral palsy, deafness, blindness or even death.

Though overwhelmed by fear, Virtue did not yet fully grasp the danger her son faced. The ordeal, however, would mark the beginning of a journey that would reshape neonatal care in West Africa.

Her son’s treatment had begun with phototherapy, but the machines available at the time were unreliable and often out of order. Even when functional, they posed their own risks. The extreme heat from the phototherapy light scorched her son’s skin, causing it to peel and darken.

As his jaundice worsened, doctors recommended a blood transfusion—a risky procedure in Nigeria due to the potential for malaria-infected blood.

“When phototherapy is not effective, when phototherapy is not available, or when jaundice is very high, there’s a procedure called exchange blood transfusion. It is draining all the blood in the baby’s body and giving the baby new blood,” Virtue explained. “That was what my son went through.”

Cradling her fragile baby, Virtue knew there had to be a better way to treat jaundice. This realisation would soon ignite a revolutionary idea: a new kind of phototherapy machine that would make jaundice treatment safer and more accessible.

The Birth of Crib A’glow

Virtue wasn’t a healthcare professional. She holds a degree in visual arts and design and works in branding and printing. But her experience with Nigeria’s inadequate healthcare system sparked her artistic problem-solving instincts.

Alongside her supportive husband, Ezoukumo, who had stood by her throughout their son’s ordeal, Virtue began asking hard questions: Why were so many babies in Africa still suffering from preventable conditions like jaundice? Why were the existing treatments so dangerous and outdated? And, most importantly, how could this change?

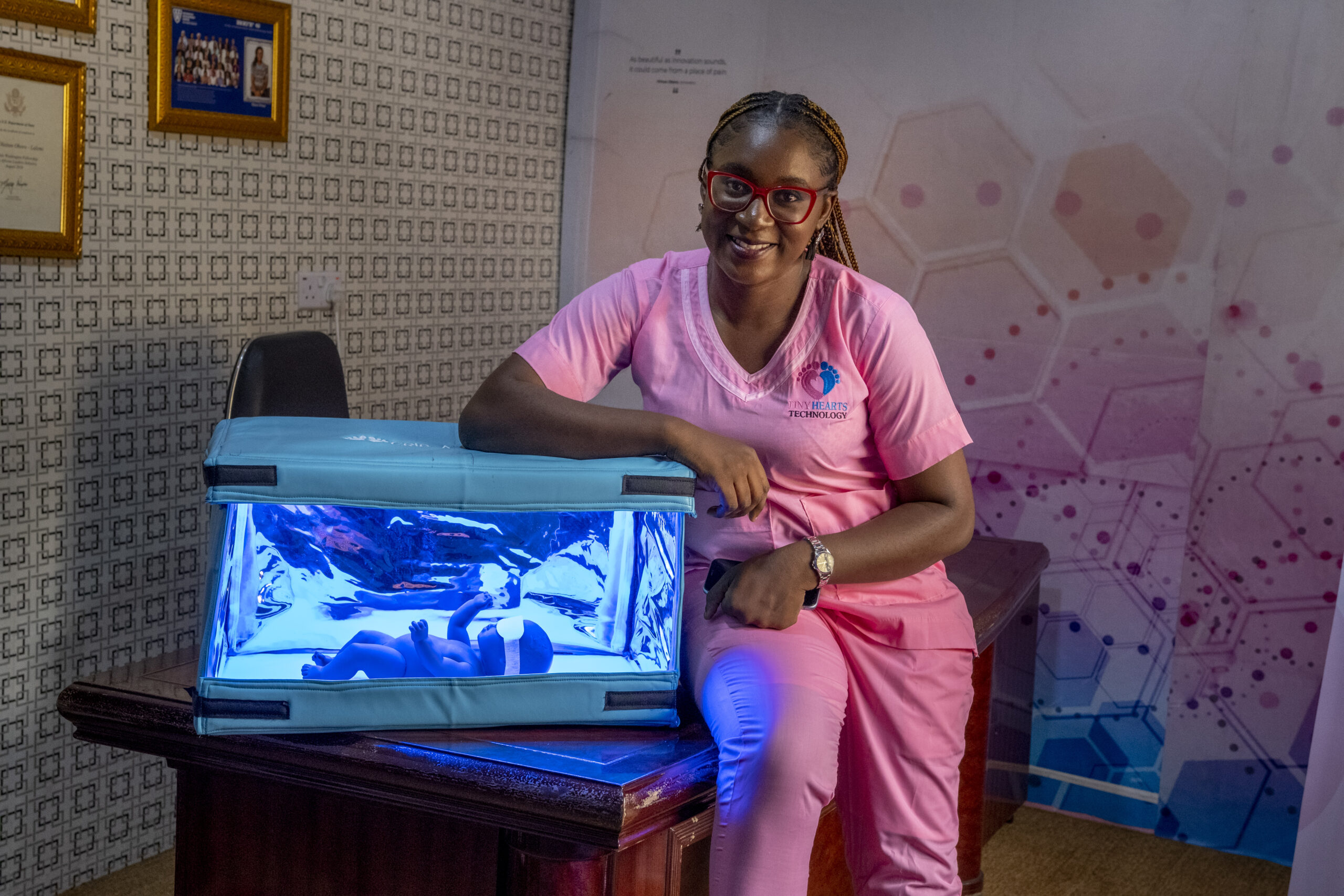

The answer came in the form of Crib A’glow—a portable, solar-powered phototherapy device. Virtue and her husband spent months sketching designs and building prototypes from their home. After nearly a year of hard work, they finally had a working model: a compact, foldable machine that could be transported easily, even to remote areas with unreliable electricity.

One of their biggest breakthroughs came when they realised the device could be solar-powered, a game-changer for hospitals and clinics in regions where electricity is a luxury. “People told me it was impossible,” Virtue remembers. But with persistence, the couple brought Crib A’glow to life, making phototherapy treatment affordable and accessible to thousands of underserved families.

Impact across West Africa

Since its launch in 2017, Crib A’glow has saved the lives of over a million babies in Nigeria, Ghana and Gambia. In areas where hospitals once had no means to treat jaundice, Crib A’glow has become a lifeline for newborns. The device not only delivers effective treatment but also offers hope to healthcare workers who previously watched helplessly as infants suffered.

Hospitals in both urban and rural settings welcomed the new technology. Traditional imported phototherapy machines cost more than double the price of Crib A’glow.

“Hospitals often run expensive generators to power conventional phototherapy units, straining their already overstretched budgets,” Virtue explained. With Crib A’glow, mothers could now bond with their babies while treatment was ongoing, addressing one of the major drawbacks of traditional phototherapy, where infants are often isolated from their parents.

Despite its success, Crib A’glow’s journey was not without challenges. Early on, many hospitals in Bayelsa, where Virtue first introduced the device, were hesitant to test it. “One hospital even insisted on testing it with rat blood before using it on babies,” she shared. But over time, as success stories emerged from other states, resistance gave way to acceptance.

Overcoming Hurdles

Developing Crib A’glow wasn’t easy. Sourcing materials to create a device that worked in diverse environments was a challenge. Inflation and high production costs, especially in Nigeria’s fluctuating economy, continue to present difficulties.

Bureaucratic delays in the healthcare sector add to the strain, making it harder to scale the innovation. “The long approval processes sometimes mean prices rise before orders are approved, which causes financial strain,” Virtue said.

But through it all, Virtue’s resolve never wavered. She recalls a low point when the weight of Nigeria’s inefficient healthcare system nearly caused her to give up. Seeing people die needlessly in the very system she was trying to improve left her feeling disillusioned. “I thought to myself, ‘What’s the point of continuing?‘” she admitted. But the thought of the babies whose lives her device had already saved—and the many more it could save—kept her going.

Recognition and the Road Ahead

Recognition of Crib A’glow’s impact soon followed. In 2017, the device won the Diamond Bank Building Entrepreneurs Today Award, selected from over 8,700 entries. That victory marked the beginning of a wave of accolades, including the Mandela Washington Fellowship, USAID funding, and the Unilever Young Entrepreneurs Global Awards. Crib A’glow’s success even caught the attention of international media, with a pivotal interview on BBC World helping to solidify its importance on a global scale.

Despite the accolades, Virtue remains grounded. “Our goal has always been to make phototherapy accessible and affordable,” she said. “Every baby deserves the chance to live a healthy life, and Crib A’glow is helping make that possible.“

Looking forward, Virtue is documenting her experiences in a forthcoming book titled Embracing Your Pain with Audacity. “No matter how dark your story or experiences are, there’s always the potential to use that pain to change lives,” she said. For Virtue, what began as a mother’s quest to save her own child has grown into a mission to save children across West Africa—one Crib A’glow at a time.

In 2015, Virtue Olaitan Oboro found herself in a challenging situation as her son struggled with neonatal jaundice, using unreliable phototherapy machines that sometimes led to dangerous treatments like blood transfusions. Driven by the inadequacies and safety issues of existing treatments, she and her husband created Crib A’glow—a portable, solar-powered phototherapy device. This innovation made jaundice treatment safer and more affordable, especially in areas with unreliable electricity.

Since its launch in 2017, Crib A’glow has saved over a million babies' lives in Nigeria, Ghana, and Gambia, offering a cost-effective solution compared to traditional machines. Although initially met with skepticism in some areas, its success stories have garnered acceptance and acclaim. Despite challenges like high production costs and bureaucratic delays, Virtue's determination remains strong, fueled by the impact her invention has had.

Crib A’glow has received numerous accolades for its revolutionary impact on neonatal care, including awards and international recognition. Virtue's drive to make phototherapy accessible continues, and she plans to share her journey in a forthcoming book, emphasizing the power of transforming personal pain into societal change.