Emmanuel Nuhu, 37, earns a living as a motorcycle taxi operator on the Pantisawa-Mararraban Lacheke route in Taraba State. The road links Pantisawa to other areas in Taraba and neighbouring states in northeastern Nigeria. However, the road is in deplorable condition. One morning in April, as he ferried farmers and their farm produce, Nuhu thought about the flooding and erosion that usually worsen traffic on the route and make his work gruelling in the rainy season.

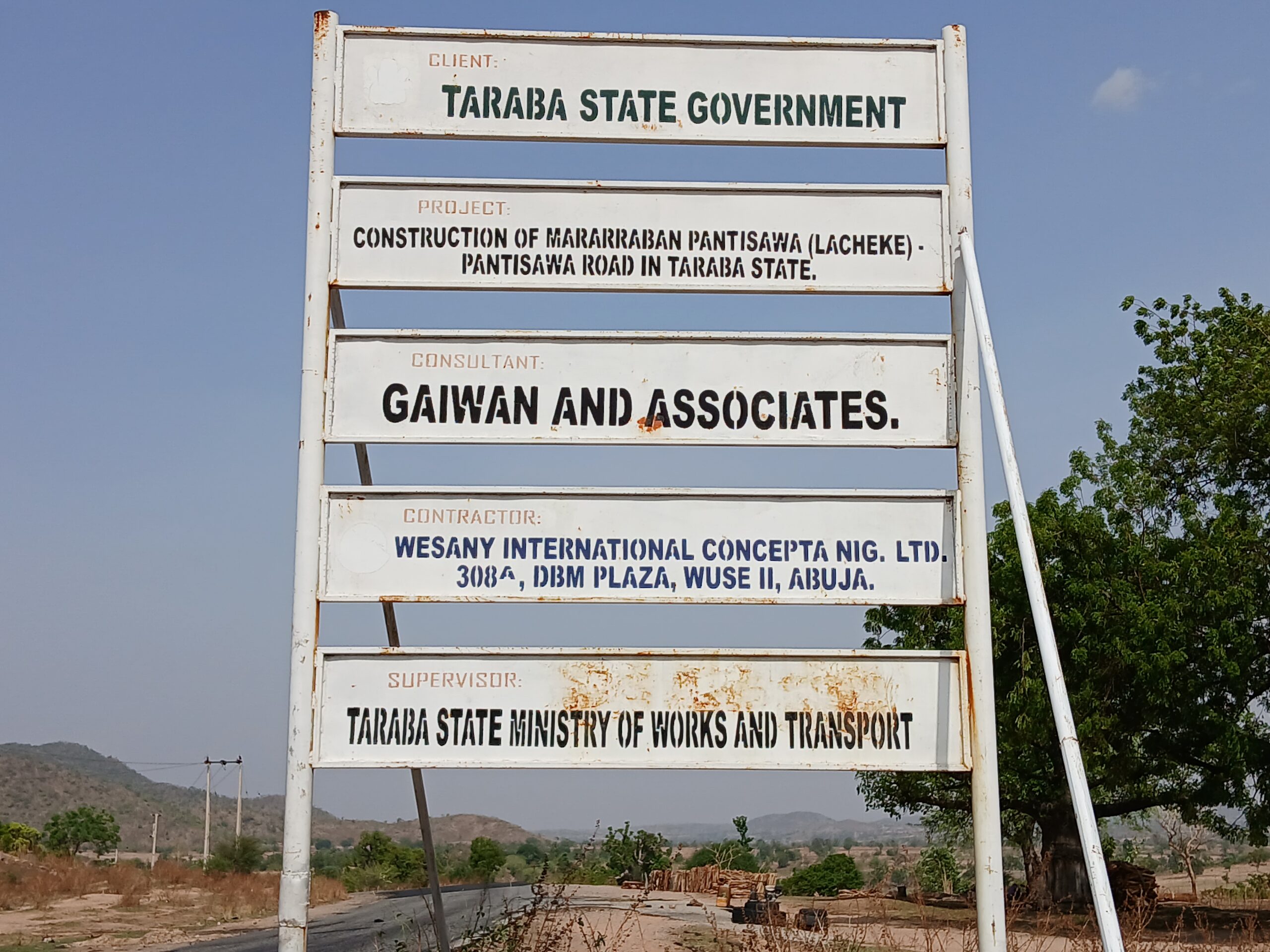

Seven years ago, then-Governor Darius Dickson Ishaku flagged off the construction of the road from Mararraban Lacheke to Pantisawa to redeem a campaign promise he made during the 2015 gubernatorial elections. The 20-kilometre road project was valued at N6.3 billion and contracted to a Germany-based firm, WESANY International Concepta.

Excitement first, then disappointment

However, work on the project stopped almost as soon as it began, dashing the hopes of residents of communities in the area and other road users.

On a Sunday in April, this reporter visited Mararraban Lacheke, where the construction took off. A walk along the smooth stretch of asphalt, bordered by a well-built culvert, lasted only 32 seconds. Across a field on the right flank, where the construction work stopped, industrial equipment such as concrete pumps, long blocks, and scrap metal littered the scene. Opposite the field, an excavator was stuck in a riverbed, and a partially completed bridge had forced commuters to fall back on the old, decrepit, narrow bridge. Beyond the bridge, the rest of the road was in disrepair.

Some villagers displayed their farm produce at a nearby market, while some men gathered over local brew. The reporter approached to speak with them about the abandoned road project, but the villagers were nervous. Instead, they led the reporter to Iliyasu Makong, whom they regarded as an authority on the construction debacle.

Mr Makong, 64, is the community leader of Lacheke. He recalled a grand ceremony that marked the project’s kick-off in 2017. “We were very happy,” he said as he sat upright on a plastic chair in his Lacheke home. “Soon after, land surveyors came to survey the road from our village to Pantisawa town. I think five or six people here in Lacheke even got compensated because the road would go through their land or houses. But many others didn’t get anything.”

A tour of the abandoned road

However, the contractor bypassed the main part of Lacheke village and paved an asphalt road two kilometres away. This section took eight minutes to ride through on a motorcycle, and the reporter and his local fixer rode slowly to get a proper view of the road. The construction ended abruptly at Nsoreng Makaranta village.

Martin Markus, a former ward councillor in Nsoreng Makaranta, was nursing a fever when this reporter approached him. Sprawled on a mat outside his home, Mr Markus corroborated Mr Makong’s account of the area’s excitement at the news of the road construction.

Mr Markus struggled to his feet to lead the reporter on a tour of the abandoned construction. “Over there, it’s a water passage, and a bridge could have been built there even without the completed road,” he said, pointing at an eroded section of the road. “During the rainy season, vehicles get stuck.”

In Lacheke, Makong highlighted the lack of a bridge in Nsoreng Makaranta as a major problem during the rainy season. “When it rains a lot and the water gets high, people can’t use the road,” he said.

Blessing, a 32-year-old farmer, said she has lived in Nsoreng Makaranta all her life.

“This road is a nightmare in the rainy season,” she said. “When it rains here, cars get stuck and sometimes can’t pass for two to three days. I use this road to travel to Pantisawa and Jalingo to buy things to sell here in Nsoreng Makaranta, but the rain often makes it impossible,” Blessing lamented.

Unlike the section of the road in Lacheke, which has an adjoining bridge, Nsoreng Makaranta lacks alternative routes. This part, where a lot of water flows in the rainy season, only has small bridge structures that weren’t completed. When this reporter and Blessing arrived at the place, they met kids playing in the water while some people fetched water from one of the holes.

Another stretch of asphalt lay four minutes from Nsoreng Makaranta, leading to the next village called Bakinya. The asphalt petered into a dirt track called Dila, where a rusty excavator lay abandoned by the roadside. The unpaved track continues until Malale, where a standard bridge has been erected. Locals say many people drowned in the Malale River before the bridge was constructed.

“We even witnessed a local government worker here who had a terrible accident and lost consciousness. However, we appreciate the past administration for setting up the Malale Bridge. That spot used to be the most dangerous for people here,” Mr Makong, the community chief in Lacheke, told the reporter.

Leaving Malale, the reporter continued a long, bumpy journey to the endpoint in Pantisawa, where he met Comfort Oliver, a food seller who plies her trade across villages in Yorro. With the messy roads, “reaching some places becomes a struggle when the rains come,” she said.

Popular for its rich agricultural produce, especially yam, Yorro is a magnet for food traders, who flood its two major markets. “We have Pantisawa on Sundays and Nyaja on Mondays. This road is the main route to these places. People from Maiduguri, Bauchi, and Gombe come to these markets, especially during the yam harvest,” Mr Makong explained.

The terrible condition of the road severely hampers food traders’ business in the district. “Sometimes, you buy yams only to meet the road flooded,” Mr Makong added.

For 31-year-old Ezra Umaru, a youth leader in Pantisawa, the road’s poor condition “means lost economic opportunities for us.”

Many Yorro residents had hoped the road project would be completed in former Governor Ishaku’s second term, which began in 2019. That year, when the governor visited the construction site, he blamed the delay on the high cost of materials. In a press release, the governor promised to disburse money to complete the project by 2021. However, five years later, nothing has changed.

Follow the money

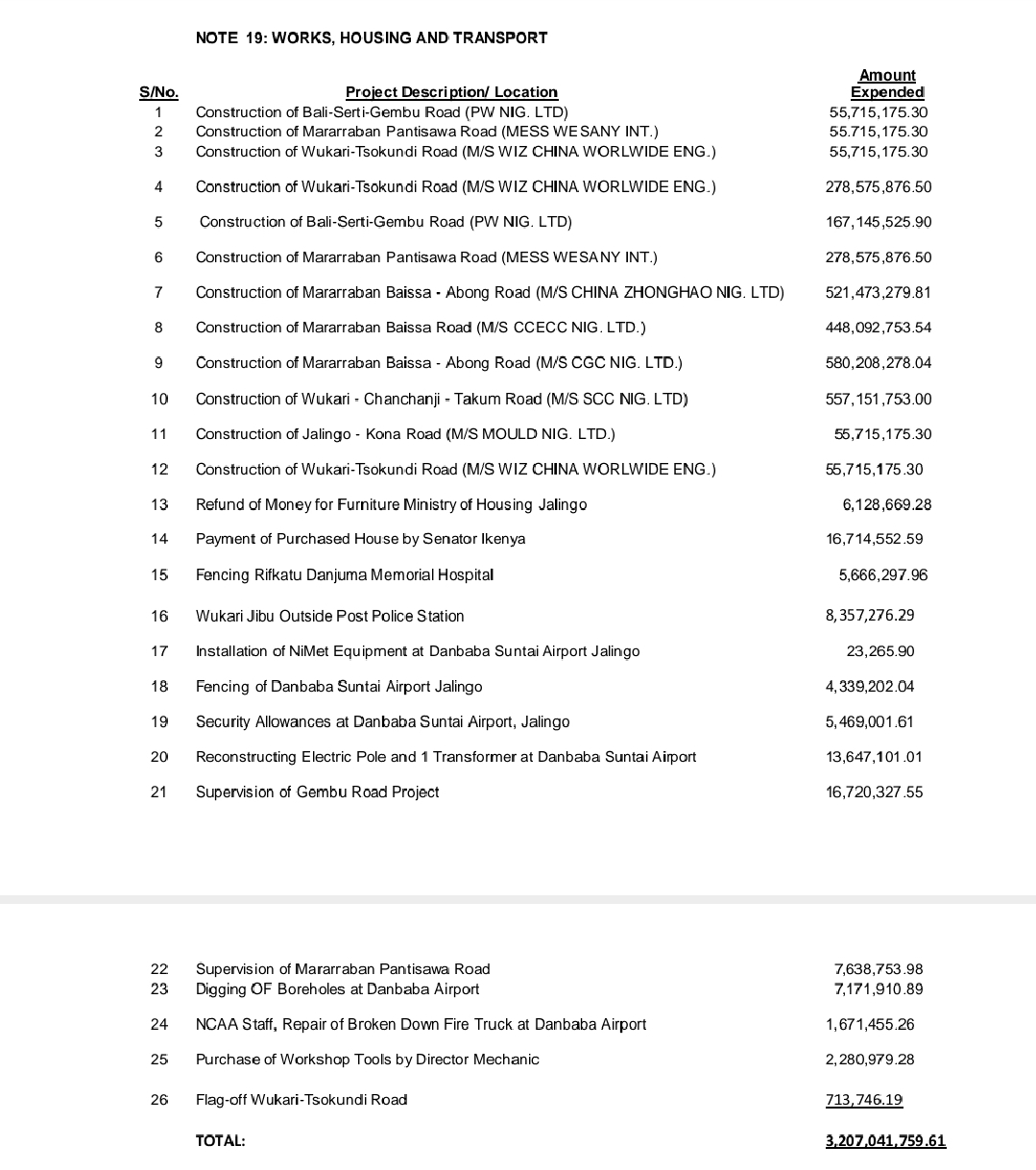

Data on the Open Nigerian States portal shows that the Taraba State government consistently budgeted funds to construct this road for four years. In 2018, N1.1 billion was allocated, followed by N800 million in 2019. In 2020, another sum of N872 million was assigned to the project. The budget for 2021 revealed a planned expenditure of N950,480,000.

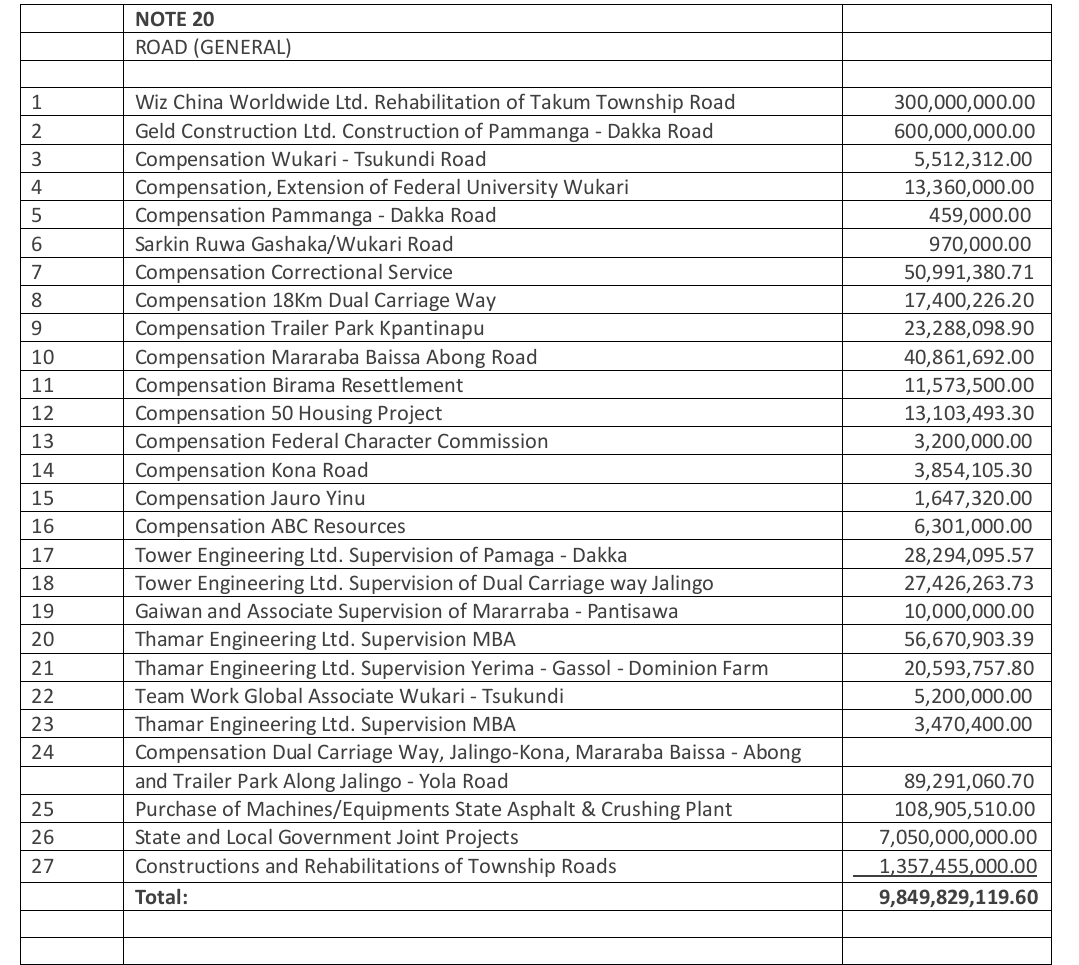

The 2019 audit report by the Taraba state accountant-general indicates that WESANY International Concepta, the project contractor, received N55,715,175.130 and N278,575,876.50 in various payment tranches. While the same report details an expenditure of N7,638,753.98 for the supervision of the road, it doesn’t identify the recipient of that fund. In another report from 2022, the audit also revealed that Gaiwan and Associates, the consulting firm overseeing the project, was paid N10 million for supervision.

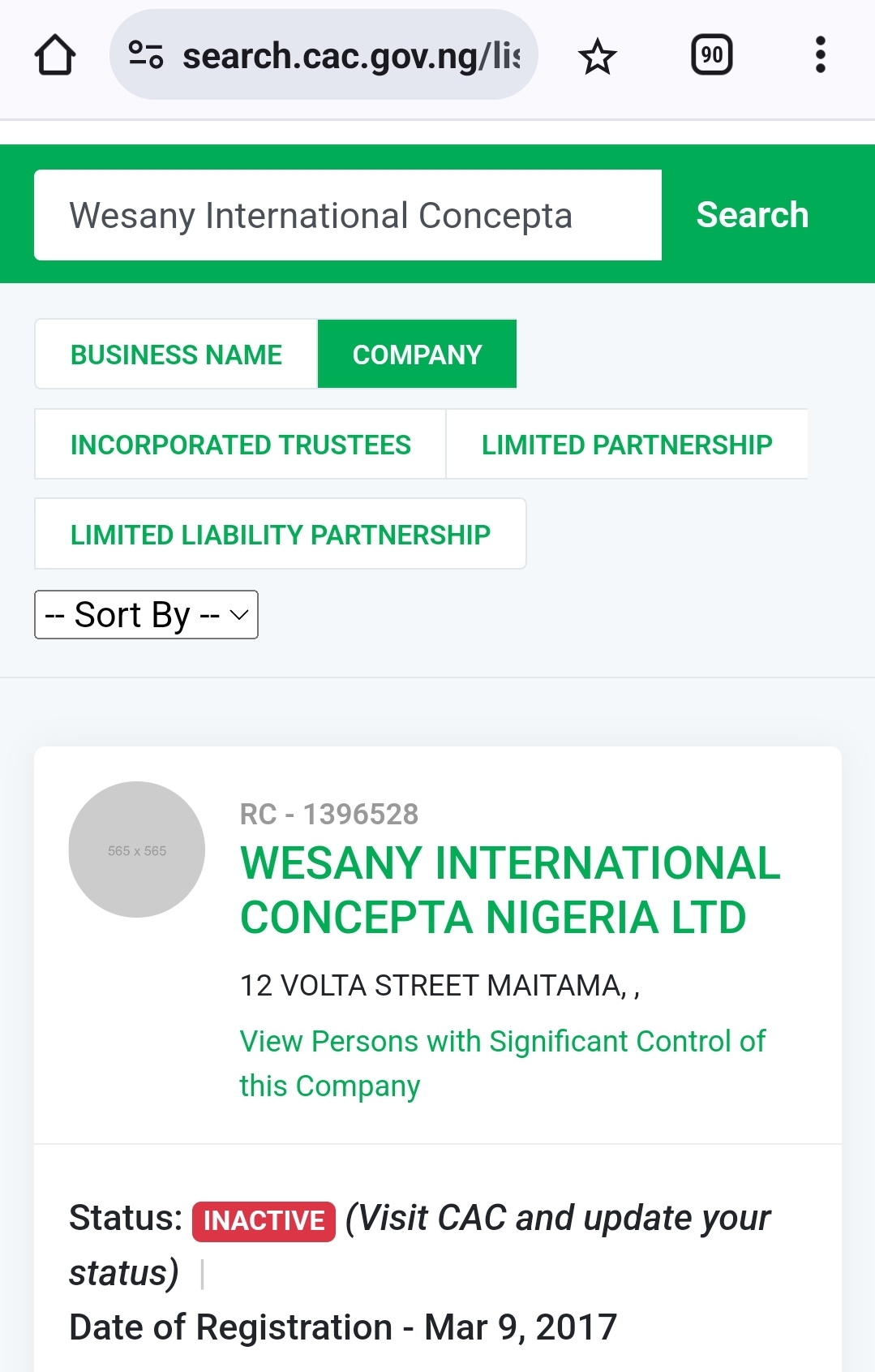

Although WESANY International Concepta registered with the Corporate Affairs Commission (CAC) on March 9, 2017, its status on the CAC website is currently listed as “INACTIVE.” The CAC designates companies inactive if they fail to update their annual returns on the CAC portal.

Similarly, a separate search on NG-Check.com also generated an “Unknown” status for the company. There is no phone number or email address.

However, the company address listed on both the CAC and NG-Check.com portals, 12 Volta Street, Maitama, Abuja, differs from the address found by this reporter on a billboard at the project site in Mararraban Lacheke, which showed the company’s location as Suite 308a, Dbm Plaza, Aminu Kano Crescent, Wuse II, Abuja.

On July 23, a visit to 12 Volta Street, Maitama, Abuja, revealed that the company wasn’t located at the registered address. The location turned out to be a residential property, as confirmed by residents in the area. There was no signage for the company there too. While attempting to photograph the building as evidence, the reporter’s phone was seized by individuals claiming he shouldn’t take pictures of private residences. After a heated exchange, the phone was returned with a cracked screen.

A visit to Suite 308a, Dbm Plaza, Aminu Kano Crescent, Wuse II, Abuja, on July 20 also yielded no results. There was no signage for the company there, and the specific suite was locked. Business owners around the neighbourhood said they had never heard about the company. A follow-up visit on July 23 yielded no new information. The company did not exist in that location.

Awarding a contract to an inactive company is a violation of Section 16(8)(d) of the Public Procurement Act 2007, which explains thus: “A bidder may have its bid or tender excluded if the bidder is in arrears regarding payment of due taxes, charges, pensions or social insurance contributions unless such bidders have obtained a lawful permit in respect to allowance, the difference of such outstanding payments or payment thereof in instalments.”

Seeking answers from the government

At 11:23 a.m. on June 10, this reporter arrived at the administrative office of the Taraba State Ministry of Works and Infrastructure (formerly the Ministry of Works and Transport). An assistant to the ministry’s staff officer claimed to be too busy to field inquiries from the reporter. She recommended the Ministry’s secretary.

As the reporter walked to the secretary’s office, the assistant called back, saying the secretary was in a meeting and she was unsure when it would end. So, the reporter waited. At 12:04 p.m., the meeting ended, and the reporter asked to see the secretary. Again, he was told to wait.

Not until 12:35 p.m. would the reporter finally meet the secretary. He explained that the project was uncompleted because of a lack of funding. “Contractors will pack their equipment and leave whenever funding isn’t provided,” he stated, sitting upright on a chair while the reporter stood. When asked if there were plans to provide the funding, the secretary directed the reporter to the Ministry’s director of Civil Engineering for details.

Following the lead, the reporter arrived at the director’s office at 12:39 p.m., but he wasn’t there. He waited under a tree until an office assistant confirmed that the director wouldn’t return that day. He decided to leave the Ministry then. The time was 2:29 p.m.

The next day, the reporter arrived at the director’s office at 12:14 p.m. He waited for eight minutes, as the director was busy. Finally, when meeting the director, the reporter highlighted the challenges suffered by the residents of Yorro, who rely on the road for their daily work. The reporter then questioned the director about why construction had stalled despite the funds earmarked for the project in the 2019 and 2022 audit reports.

“These are official matters. Some of this information can only be released by the commissioner or the permanent secretary. I’m not responsible for releasing information without permission from them. Gentleman, I’m working under an authority. I’m not on my own,” said the director, suggesting that the reporter forward his request to the ministry’s commissioner.

As he left the director’s office, the reporter asked a staff member for directions to the commissioner’s office. The commissioner was said to be out of office. The next morning, on June 12, when the reporter returned to the office, the commissioner was still unavailable.

By June 13, the commissioner still couldn’t be reached. Months earlier, Mr Makong and other community leaders had considered meeting the commissioner of Works and Infrastructure.

“We feel the commissioner can connect us with the governor so we can beg him to reason with us. But I’m still sceptical about the decision,” Mr Makong told this reporter.

A plea for intervention

While the community leaders have shelved their decision to approach the government, the plight of Yorro residents remains dire, especially as the rainy season intensifies. Trips that once took 30 minutes now last between 60 and 70 minutes, Nuhu, the motorcyclist, complained.

Residents like Comfort and Markus continue to plead for government intervention in providing at least standard bridges to ease movement on the deplorable road.

“Government officials sometimes use this road, and whenever they learn it is flooded or jammed with vehicles, they will return to the city where they came from. It’s the common man who’s left to suffer at last because they must pass through to get to their homes or destinations. We know the government has workloads, but we still beg them to remember our needs,” Mr Markus bemoaned.

For now, the road to economic prosperity remains blocked, forcing residents to grapple with the difficulties of incomplete infrastructure and broken promises.

Support for this report was provided by the Centre for Journalism, Innovation and Development (CJID).

Emmanuel Nuhu, a motorcycle taxi operator in Taraba State, Nigeria, struggles with the bad condition of the Pantisawa-Mararraban Lacheke road, especially during the rainy season. Seven years ago, the road construction was initiated by former Governor Darius Dickson Ishaku with a project valued at N6.3 billion, but work halted soon after commencement, leaving residents disappointed.

A tour of the area reveals incomplete stretches of road, abandoned equipment, and the severe impact on local communities. Key local figures, including community leader Iliyasu Makong and former ward councillor Martin Markus, recount their excitement and subsequent disappointment over the project's stagnation. Regular flooding exacerbates travel difficulties, impacting daily life and economic activities, especially for farmers and traders.

Despite consistent state budget allocations for the project, including significant funds earmarked from 2018 to 2021, the road remains unfinished. The contractor, WESANY International Concepta, is currently marked as inactive by the Corporate Affairs Commission, raising questions about fund disbursement and project supervision. Efforts to get answers from the government have been met with delays and limited responses. Residents continue to plead for intervention to complete the road and build essential bridges, crucially needed for their livelihood and safety.