By Olayide Soaga

As a child, Najib Murshid always felt a yearning for something his little hands could not grasp and a life that seemed out of his reach. His earliest childhood memories were seeing his peers running around and playing hide-and-seek in his community—in Jos, Plateau State—with smiles on their faces.

Much as he desired to join them, he could not as he was paralysed. At age 4, Murshid’s body was hit with polio. Though he survived, the disease paralysed his legs, leaving him to painfully crawl on all four limbs when help was unavailable.

“I felt like a horrible person because of my condition,” he recalled. “It was really difficult to move from place to place because I could not buy a wheelchair and my family could not afford to buy a wheelchair for me.”

Murshid is one of the 11 million polio survivors in Nigeria, racked with paralysis, many of whom are left without mobility aid. It took the intervention of a special-purpose nonprofit that traces its reason for existence to a biblical story for Murshid to get his first wheelchair.

Fighting the virus but neglecting survivors

Poliomyelitis, commonly known as polio, is a highly infectious viral disease that attacks the nerves in the spinal cord and brain stem in under-5 children. The disease is transmitted through contact with faeces, cough droplets from infected persons, or contact with contaminated food or water.

Although polio can be prevented with a vaccine, the effect of its more severe variant, called paralytic polio, could be paralysis, difficulty breathing, or even death. The World Health Organisation estimates that 5-10% of global polio cases result in death.

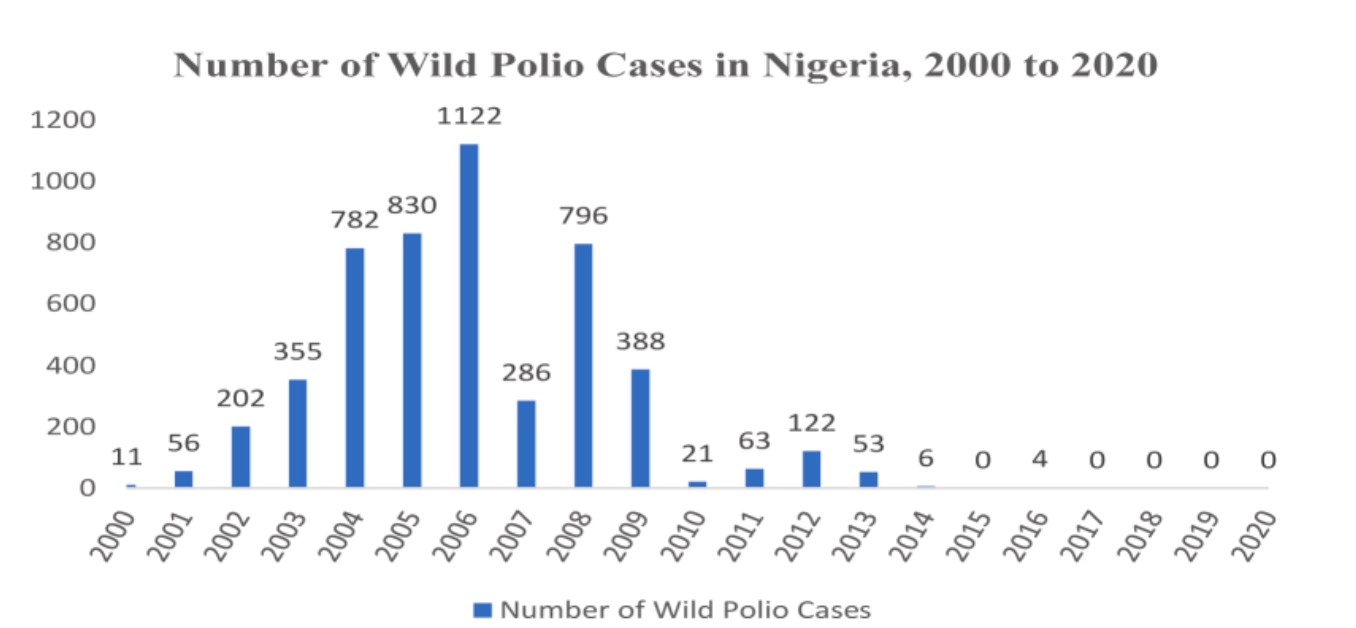

Between 2000 and 2013, Nigeria recorded 5093 polio incidents, making it the second country with the highest cases after Afghanistan. However, by 2020, the country had become free of polio, with only 4 cases between 2014 and 2020—thanks to concerted efforts by the federal government, UNICEF and WHO through vaccines and sensitization campaigns to fight the virus.

However, state interventions have focused primarily on curbing the spread of the virus using vaccines; little or no support has been given to survivors—especially those who cannot afford mobility aid. This compounds the woes of victims and drives them further into the rut of despair.

Many Nigerian polio survivors with paralysis cannot afford mobility aids like wheelchairs and crutches, which are often priced above their means. A wheelchair here sells for between N134,000 ($91.72) and N300,000 ($205), way below the country’s N30,000 ($20.54) minimum wage.

‘The beautiful gate’

Like Murshid, Ayuba Gufwan is a polio survivor who dropped out of school after he became paralysed as a child and didn’t have a wheelchair.

“There was no way I could get to school crawling on my hands and knees,” he said. By the time his uncle bought him a wheelchair, Gufwan was already 14 years old.

“With the wheelchair, [I] was able to go to school and continued schooling until I completed my primary school, went to the College of Education, came back to Jos, picked up a teaching job, and then went back to the University of Jos, where I studied law,” Ayuba, now 52, told Prime Progress.

As a Christian boy, Gufwan was familiar with the Biblical account in Acts chapter 2 verses 1-3, where Peter, one of Jesus’ disciples, healed a lame man who often sat by a gate called Beautiful to beg for alms. Gufwan interpreted his uncle’s gift of a wheelchair to as a miracle too.

This would later inspire him to found the Beautiful Gates Handicapped People Centre in 1998 in Jos—a nonprofit he named after the Beautiful Gate in the Bible. The group builds mobility materials like wheelchairs, crutches and others to distribute them to people with disabilities, especially polio survivors. It was this organisation that gave Murshid his first wheelchair after he heard about it “from someone in my community,” he said.

This is “a calling from God,” said Gufwan, who resigned from his job as a teacher of history and Christian religion knowledge to focus on the nonprofit. He is a member of the Church of Jesus in Nations, where he previously served as a member of the welfare committee and the choir in his local assembly. He is a member of the men’s fellowship now.

“Since we cannot heal people like Jesus, Peter and Paul in the Bible, we want to ameliorate their sufferings. We do not believe that if you lose your legs, that is the end of you. “We only believe disability is a limitation and a challenge waiting to be overcome. So we set up the beautiful gate to provide mobility appliances, wheelchairs, tricycles, crutches and other mobility appliances that polio survivors need so they can start life.”

The Beautiful Gate has distributed 32,000 wheelchairs and other mobility materials to people with disabilities in Plateau and other northern Nigerian states.

Speaking about how he uses grant and donation models to raise funds, he said, “I usually appeal to people out there to support people living with disabilities so that they can overcome their immediate needs, such as walking sticks, wheelchairs, and others.”

The process of doling out wheelchairs and other mobility appliances begins with the nonprofit announcing the availability of wheelchairs through community leaders, student union leaders, the Rotary Club, women’s groups, and associations of people with disabilities who spread the word to those in need in their networks.

“I heard they were distributing wheelchairs to people on the radio, and I went,” said 52-year-old Aliyu Isiaka, who has a spinal injury.

Before distributing the aid, the nonprofit assesses each individual’s needs to provide appropriate mobility aid.

“Whether it is a regular wheelchair, tricycle wheelchair, crutches, pair of prosthetics or artificial limbs, walking sticks or walking limbs, we look at them and give them mobility appliances based on their conditions,” he said.

Inflation worsens limitations

In the early days of the organisation in Jos, Gufwan said its challenges included not having “an office, and a workshop, and sometimes, we used to work under a mango tree to produce wheelchairs.”

With a workforce of 100 employees, the foundation has expanded beyond those limits, but inflation-triggered increases in prices of production materials continue to cramp its capacity to churn out enough mobility aids to meet the demand. Nigeria’s inflation rate has climbed to a 3-decade high of 33% in the last three years.

“All of the appliances people with disabilities use are capital intensive. Until two or three years ago, one wheelchair used to cost us around N55,000, but with the current hike, it is over N100,000 to provide one of those,” Gufwan said. “We are trusting God for provision.”

Notwithstanding, the group remains a beacon of hope for many survivors, like Murshid and Aliyu Isiaka, the latter of whom expressed his gratitude: “I am grateful to the Beautiful Gate for giving me a wheelchair and making my dreams of mobility a reality.”

This story was supported by the Centre for Religion and Civic Culture at the University of Southern California through its global project on engaged spirituality.

Najib Murshid, a polio survivor from Jos, Plateau State, Nigeria, faced immense challenges after being paralyzed at age four, lacking access to mobility aids. He is among the 11 million polio survivors in Nigeria, many of whom live without necessary support. Despite eradication efforts reducing polio cases, state interventions have primarily focused on vaccination, neglecting survivors' needs.

Ayuba Gufwan, another polio survivor, founded the Beautiful Gates Handicapped People Centre in 1998, inspired by a biblical story. This nonprofit provides wheelchairs, crutches, and other mobility aids to disabled individuals, mainly polio survivors, distributing over 32,000 mobility devices in northern Nigeria.

The organization relies on grants and donations and spreads news about available aids through community channels. However, inflation has significantly increased production costs, limiting their capacity. Despite these challenges, Beautiful Gates remains a critical source of support, profoundly impacting beneficiaries like Murshid and Aliyu Isiaka, who have gained mobility and hope through the nonprofit's work.

This story receives support from the Center for Religion and Civic Culture at the University of Southern California.