Ajoke Ayo’s face bore a strange mix of frustration and relief as she sat under a luxuriant tree one afternoon in February. She was positioned in front of a hostel for people with leprosy, a few meters away from a leprosarium nestled in a thick forest between Omu-Aran and Oke Onigbin villages in Nigeria’s north-central state of Kwara.

Twenty years ago, 42-year-old Ayo arrived at the hospital after part of her hands and toes were eaten off by leprosy, an infection that she contracted at age 9 and which her parents initially interpreted as a demonic attack.

“My family embarked on a journey, consulting various native doctors and spiritualists in pursuit of a remedy. We expended significant resources [without positive outcome] before eventually arriving here twenty years ago,” Ayo recalled.

The leprosarium, run by the Evangelical Church Winning All (ECWA), is driven by a vision to “embrace all” and provide care to the ostracized. It provides free treatment, shelter, and prayers for people suffering from leprosy and other skin diseases. Its ethos of love is even encapsulated in its name, Oke Igbala Leprosarium, which roughly translates as a “mountain of deliverance.” It serves as a beacon of hope for people with leprosy in Kwara and neighboring states.

Since arriving at the leprosarium, Ayo has lived in the hospital’s adjoining hostel, as the fear of discrimination would not let her go home. This saddens her deeply, she said.

“I wanted to return home, but by the time I sought treatment here, my body was already halfway gone,” she said. Today she takes solace in her healing, as she no longer worries about losing more of her body parts.

A neglected disease

Leprosy is one of 20 diseases the World Health Organisation (WHO) describes as neglected tropical diseases affecting over one billion people globally, primarily very poor communities exposed to the various pathogens and toxins that cause the diseases. They are labelled “neglected” since they are hardly mentioned in global health discussions.

Victims of leprosy often experience muscle paralysis or weakness; nerve disorders; eye problems with the potential to lead to blindness; skin ulcers; patched, coloured and dry skin; and growth on the face among many other symptoms. Although curable, early detection and treatment are crucial to preventing disability.

Yet victims like Ayo are condemned to a life of unemployment, abject poverty and crushing loneliness as society isolates them for fear of contracting the disease. In Nigeria, many such victims resort to begging for alms on the street.

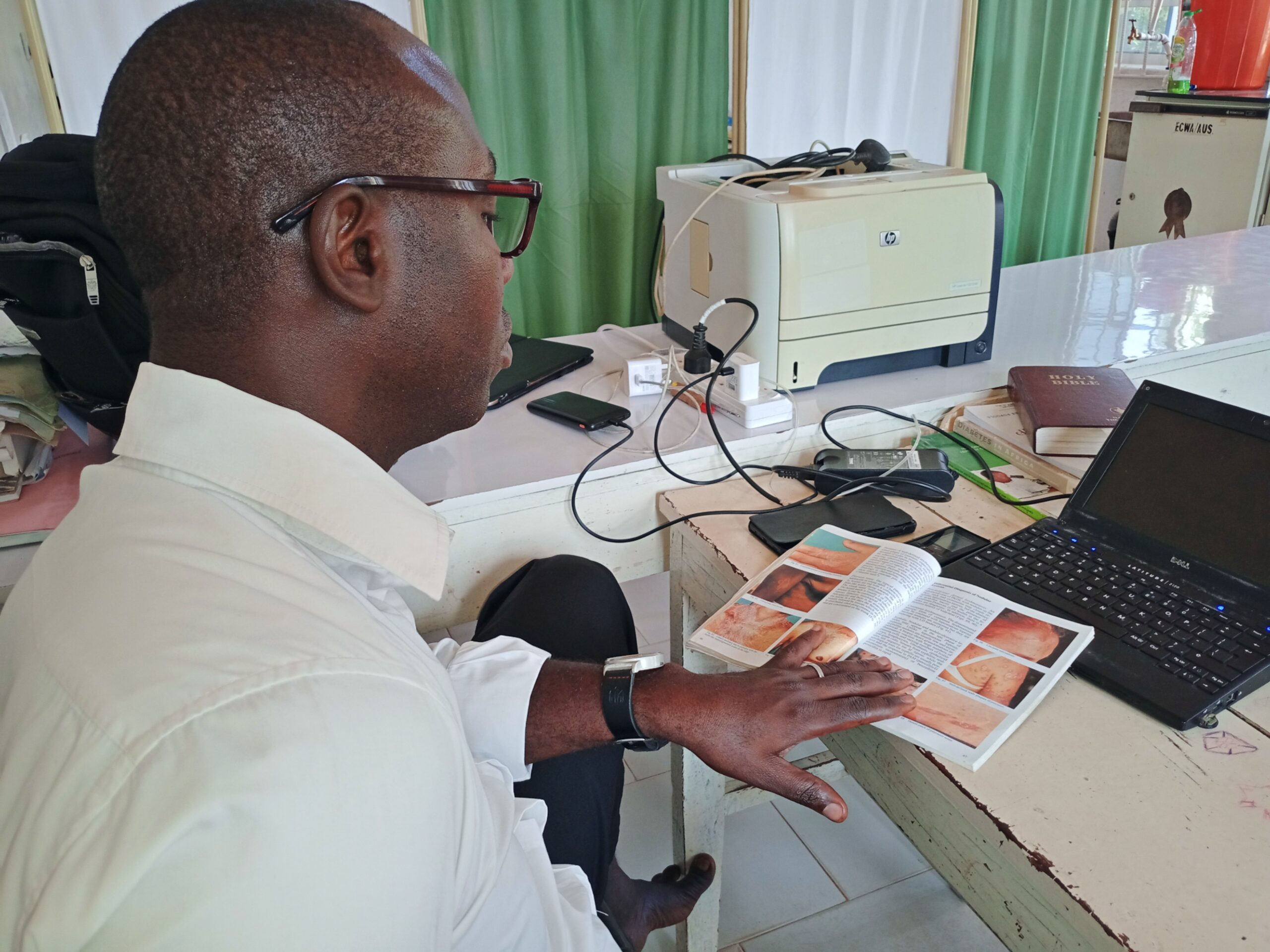

‘Doctor missionaries’

Grassroots communities across parts of Nigeria have long grappled with leprosy, and at different times, Christian missionaries have intervened to help. In fact, the Oke Igbala leprosarium traces its history back to 1943, when a Canadian missionary named Dr. H. Herbold on evangelical duties encountered numerous individuals with leprosy in present-day Kwara State. He was particularly pained by the strong discrimination leprosy victims faced.

Herbold was a missionary under the Society International Ministries (SIM), formerly the Sudan Interior Mission (SIM). As a physician familiar with skin disease associated with leprosy, Herbold incorporated skin treatment into his missionary work, gathering 26 leprous victims across villages and caring for them.

Herbold’s efforts, however, were met with hostility from the host communities, who insisted that he stop caring for the patients in their neighborhood due to fear of infection. Left without any choice, Herbold and his wife, a nurse, moved to a thick forest on the outskirts of Omu-Aran, which was considered no man’s land at the time. In his new environment, Herbold and his wife started a new leprosy clinic, which they managed until the 1960s.

Upon the end of his missionary duties, Herbold departed Nigeria, which halted operations at the medical center for many years. Drawing inspiration from Dr. Herbold, Evangelical Church Winning All (ECWA), founded in 1954, took over the reins of the clinic, in partnership with SIM.

However, a shortage of resources and limited equipment blighted the hospital’s operations in the early 1980s. Around the same time, Leprosy Mission International arrived in Nigeria as part of its global mission to fight leprosy.

ECWA’s leprosy hospital became the first port of call for the mission, providing support to people with leprosy and infrastructure for the hospital before it eventually relocated to Abuja. This support ceased in 2009 due to a shortfall in resources.

Nevertheless, the hospital has continued operations to this day, surviving manifold difficulties with a workforce of 23 staff. The hospital is prominent in skin disease treatment and is recognised as the preferred medical outlet for leprosy and tuberculosis in Kwara and neighboring states. It was this hospital that Ayo would later come for healing.

Sustaining the Mission

Support from the ECWA church and foundations such as the Damien Foundation, a medical nonprofit providing support to people with tuberculosis and leprosy, ensures that the leprosarium stays in operation. The 25-room hostel (housing Ayo and other older patients) was built and donated to ECWA by the Damien Foundation in 2019. Missionaries and churches also visit occasionally to provide moral and financial support to the patients.

“[The] Oke Igbala leprosarium] receives a yearly grant of N3,000,000 (about $2,600) from the ECWA church management,” said Samuel Abiodun, the administrative officer.

The state government, which uses the facility as a referral center for tuberculosis and leprosy, also pays the hospital N100,000 monthly.

Meanwhile, part of why ECWA Church upgraded the clinic to a hospital was to ensure that it could treat non-leprosy victims with ailments like malaria for a fee to support its operations. But non-leprosy patients hardly patronize the hospital because of its association with people with leprosy, defeating its essence.

Ultimately, the funding the hospital receives is inadequate to cover its operations. “The salaries are insufficient,” said Olawale Ezekiel, head of the laboratory, who has worked in the leprosarium for 15 years.

Poor remuneration has forced many workers to leave, and those who stay do so for “humanity and love for God’s creation” because “life is beyond money,” said Ezekiel, who had considered leaving but decided against it.

“This is my God-ordained ministry. I love these people and whenever the thought of leaving this place comes to mind, I begin to wonder who will help them out [if I leave]?” he asked.

The hospital’s financial crisis is well known to the patients too, making them more appreciative. “Despite being in debt, they continued to assist us with food and medication,” said 45-year-old Ahmad Mohammad, who worked as a vulcanizer in Lagos State until an ulcer in his left foot landed him at the leprosarium.

Breaking free: Ever possible?

Over the past decades, Nigeria has waged a war to break free from leprosy. In 1998, it achieved its target of recording one case maximum per 10,000 people at the national average. However, the numbers were messy at the state and community levels.

“Leprosy remained endemic at the subnational level,” said Charles Nwafor, director of RedAid Nigeria, which supports people suffering from exclusion and poverty-related diseases. “While certain states have prevalence rates lower than the national target, others exhibit higher rates. At the local government level, endemic leprosy persists in certain areas, where more than one person per 10,000 population is diagnosed with the disease.”

This failure accounts for why the country now registers over 1,000 new cases annually, indicating difficulty in combating the disease effectively. Worse still, national infrastructure for caring for people with leprosy is limited and not easily accessed.

“For people who are newly diagnosed with leprosy, 98% of them are funded by non-governmental organisations,” Nwafor said.

In the southwest and central region of Nigeria, ECWA’s Oke Igbala Leprosarium remains one of the most active, amid its challenges. In addition to providing shelter, it has helped at least 1,000 patients overcome leprosy.

This story was supported by the Centre for Religion and Civic Culture at the University of Southern California, through its global project on engaged spirituality.

Ajoke Ayo, a woman afflicted by leprosy since childhood, has found solace after two decades at the Oke Igbala Leprosarium in Kwara, Nigeria. This facility, run by the Evangelical Church Winning All (ECWA), provides free treatment and support to those suffering from leprosy and other skin diseases, adhering to a mission of compassion and inclusion.

Leprosy, deemed a neglected tropical disease by the World Health Organization, severely affects marginalized communities globally, inducing symptoms like paralysis, nerve disorders, and severe skin conditions. Though curable with early intervention, many victims, like Ayo, face severe social stigma, unemployment, and poverty.

The Oke Igbala Leprosarium, originally established by Canadian missionary Dr. H. Herbold in the 1940s, has seen periods of financial struggle but continues to operate with support from various organizations, including the Damien Foundation and ECWA. Despite the critical help offered, the facility continually battles inadequate funding, affecting staff salaries and hospital operations.

Leprosy in Nigeria remains a significant challenge, with the country recording over 1,000 new cases annually. Although national targets were met in 1998, higher prevalence persists at state and local levels, revealing endemic conditions. Non-governmental organizations predominantly finance care for new patients, demonstrating the critical gap in government support.

Efforts toward sustaining the mission of Oke Igbala Leprosarium continue, providing essential care and a ray of hope to over 1,000 patients amidst ongoing challenges.